Exhibitions are great. They can be an adventure. They give us recourse to real, living, breathing objects. Spending time with art can be like looking in a mirror, helping us better understand ourselves.

Frankly, exhibitions can also help us get out of the house. However, as the nights draw in and autumn beckons, the prospect of milling around a gallery becomes increasingly less appealing than the idea of reading a good book on the sofa. Today, I am mindful of this.

I bring to you three books which might go some way to providing you the gallery experience from the comfort of your own cosy nook.

Before I got into Art History, I was an English Lit major. I’ve put in a good shift in the library - and in fact my introduction to the arts came through my reading of novelists like George Elliot (who brought me to Ruskin), Virginia Woolf (who brought me to Modernism), and Alasdair Gray (who brought me to William Blake). So I’m confident that I can identify what makes a novel worth reading: or at least, I’m well positioned to try…

I’ve collated here three books – one classic, one contemporary, and one wildcard – which I think will appeal to a whole range of readers who might want to think more about art.

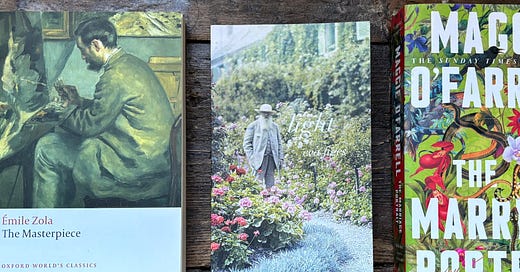

For the Serious Literati: Émile Zola’s The Masterpiece (1886)

Image: Paul Cézanne, ‘Self Portrait with a Palette’, c. 1885.

While I implied that these recommendations would be cosy, I assure you that this one is not. The Masterpiece is a tragedy. It centres around a painter, Claude Lantier, who operates in Paris during the Second French Empire (1852-1870). It explores his obsessive pursuit of an elusive ‘masterpiece’ which he believes will solidify his legacy as a great artist.

Not only does this work touch on themes which come up when we think about art – inspiration, obsession, and failure – but it also provides an interesting window into the Bohemian art community of nineteenth-century Paris, and the tensions which were then-bubbling between the Impressionists and the conservative art establishment. Claude, for example, talks a lot about en plein air painting, the practice of painting outside, directly from nature. It is a technique closely associated with French impressionists like Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro.

Zola (1840-1902), who was childhood friends with Paul Cézanne (who we now recognise as a master), had seen first-hand how his contemporaries in the art world struggled to gain recognition for their work. Like Zola’s protagonist, Claude, Cézanne was often rejected by the official Salon and lived much of his early life in relative obscurity, facing harsh criticism for his unconventional style. Cézanne, who recognised himself in Claude, was deeply hurt by Zola’s portrayal, and this unfortunately led to the end of their lifelong friendship!

If you are really brave, you can try reading this in the original French. Because I am a coward, I used the Oxford World’s Classics translation by Thomas Walton. The writing is nonetheless beautiful:

It was like a window flung open on all the drab concoctions and the stewing juices of tradition, letting the sun pour in till the walls were as gay as a morning in spring, and the clear light of his own picture, the blue effect that had caused so much amusement, shone out brighter than all the rest. This was surely the long-awaited dawn, the new day breaking on the world of art!

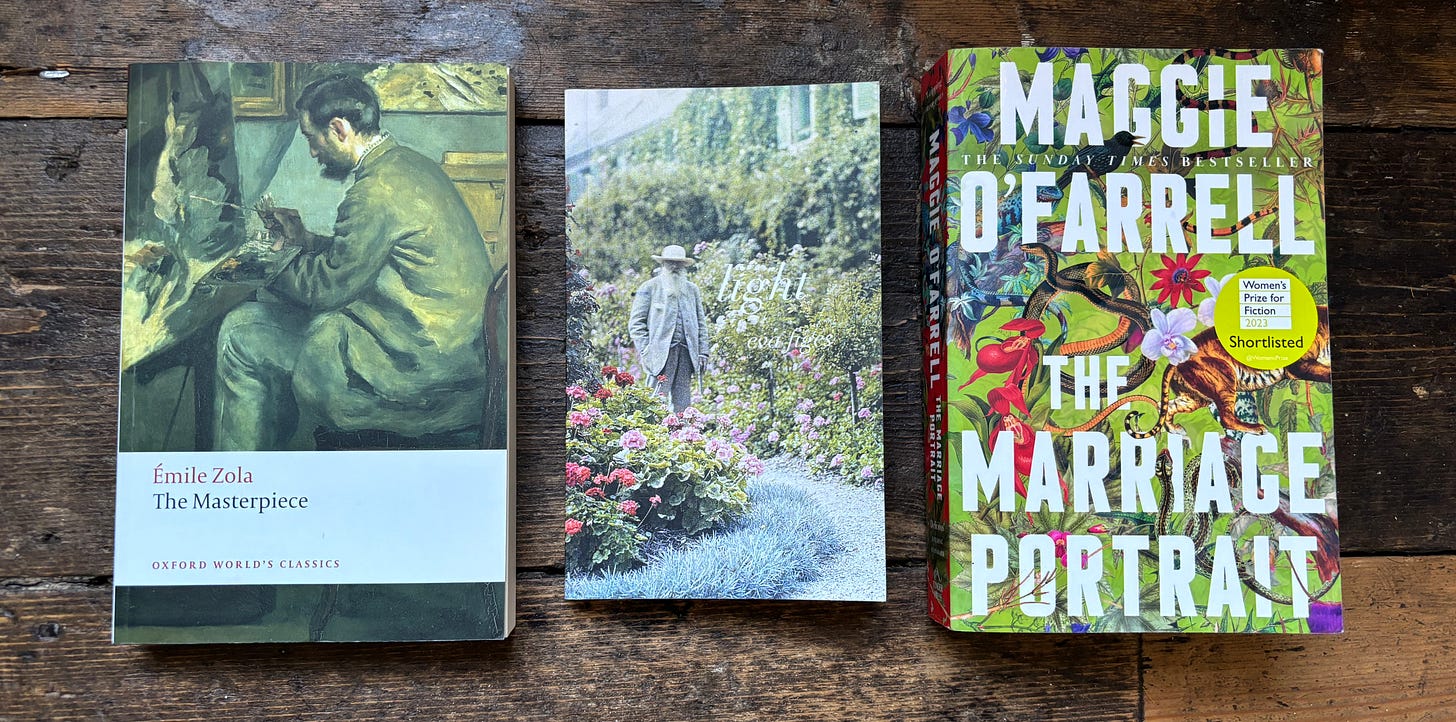

For casual readers: Maggie O’Farrell, The Marriage Portrait (2022)

Image: Alessandro Allori, Portrait of Lucrezia de’ Medici (1545-1561), c. 1560.

I read Maggie O’Farrell’s popular novel Hamnet (2020) and, I will admit, I did not finish that book. I don’t generally enjoy works which present real, historical people as fictional characters (I don’t want a Shakespeare sex scene! I really don’t). With that said, she does exactly the same thing in The Marriage Portrait (2022), and I liked it. This one fictionalises Duke Alfonso D’Este, who was the ruler of the Italian province of Ferrara in the early sixteenth century, and his young wife Lucrezia de’ Medici (about whom we know little other than that she was married to Alfonso at fifteen!).

I’m recommending this one for a number of reasons: firstly, it’s a good, exciting, easy read. It was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2023. Moreover, for those who never had the chance to study art in Renaissance Italy, and who don’t want to read a history book about it, I think this novel offers a really excellent insight into Italian nobles and their patronage of the arts.

The title refers to a real-life portrait of Lucrezia which was commissioned by Alfonso from Alessandro Allori in 1560 (just after the High Renaissance). These types of works were traditional marriage gifts. Like many forms of art in Renaissance Italy, however, they also served as vehicles of wealth, power, and ownership.

Thematically, this novel explores the struggle for female agency in a profoundly patriarchal society. Told entirely from Lucrezia’s perspective, it gives a voice to the silent figure in Allori’s painting, and causes us to think about the tensions inherent in these kinds of old portraits: can we really see them as a representation of an individual? Or are they simply a projection of the wealthy patron and their values?

O’Farrell has a dedicated fan base who sing the praises of her distinctive prose. It is fast, talkative, and filled with adjectives. It’s fairly raw, and might not appeal to everyone, but it is certainly effective in conveying profound emotion.

Lucrezia regards the portrait; she stares; she cannot look away. It is at once scaldingly public and deeply private. It displays her body, her face, her hands, the mass of her once-long hair, which ripples down either side of the dress, with a brand of insolent indifference to its geometric pattern, but it also excavates that which she keeps hidden inside her. She loves it, she loathes it; she is dumbstruck with admiration; she is shocked by its acuity. She wants the world to see it; she wishes to run and cover it again with the cloth at the artist's feet.

For the poets: Eva Figes, Light (1983)

Image: Claude Monet, ‘Water Lilies’, c. after 1916.

Here’s my wildcard: Light. If you’ve ever read a novel by Virginia Woolf, enjoyed it, but thought that it was a touch too long, you will love this book. It’s essentially an Impressionist painting in the form of a 150-page novella. It takes place over the course of one day, and centres around the life of Claude Monet and his family in Giverny, France, in 1900.

It has the dreamy summer-holiday feel of Call Me By Your Name (André Aciman, 2007), combined with the light, floaty, soft narrative voice of The Waves (Woolf, 1931). It is a meditation on subjectivity, perception, time, and light. It has no real plot, and no protagonist. It’s focused on the senses and the seasons. It’s a work of synaesthesia. Beautiful.

But the light was changing now, and it was time to give up on this particular canvas. A faint streak of rose flushed the sky beyond the trees. Everything would change now, touches of pink would show in the water which would begin to shine, glinting with rose and gold, the skin of the water would become a living thing, running with fragments of the world, washing them downstream into the following night.

Fin.

Thanks, Rebecca, for this great post. I ordered The Masterpiece right away!

Zola's book sounds right up my alley—I remember reading Thérèse Raquin ages ago and loving it and thinking I should read more of his work.

100% agree with you about not wanting a Shakespeare sex scene 😂