One month ago, on 7th May 2025, the Vatican closed its doors and everyone inside it undertook a vow of secrecy. Pope Francis had died only sixteen days prior, and the cardinals were compelled to undertake a papal election called a Conclave.

Conclave comes from the Latin ‘cum clave’, meaning ‘with key’: that is, ‘locked in’. It is crucial that the cardinals make this decision without outside influence. Until they make a unanimous agreement, no one can leave.

The recent conclave, like all conclaves since 1492, took place in the Sistine Chapel. This is a gargantuan space containing some of the most famous artwork in the world.

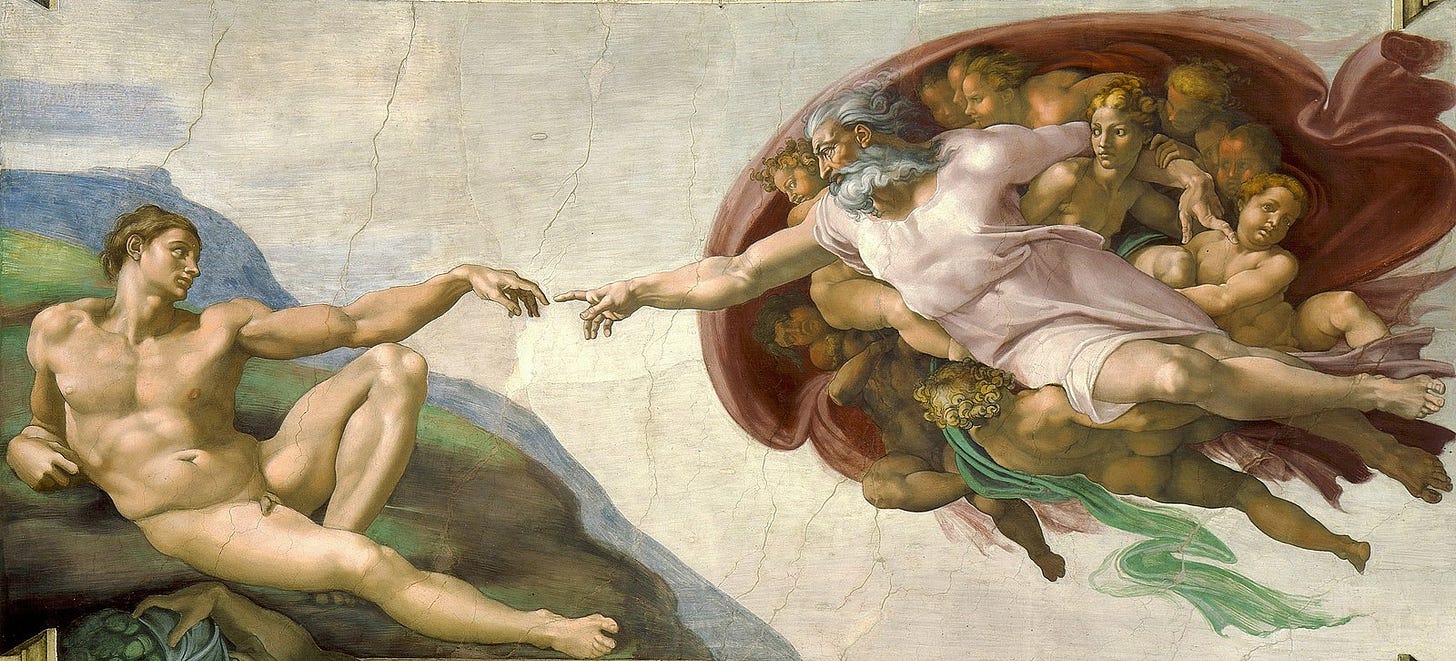

Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam sits in the middle of the ceiling. It offers a constant reminder to the cardinals of their position in the divine hierarchy. Though the Pope may mirror God on earth (and indeed Adam, in this picture, mirrors God) he ultimately owes everything to his Creator.

The early modern Catholic church placed a profound emphasis on the arts. Beautiful objects were commissioned as manifestations of the divine, and also of monetary and political power. But Michelangelo’s paintings in the Vatican are a bit more complex than that. They aren’t just expressions of the wealth and pomp of the Catholic church. Instead, more often than not, they also serve as warnings against the temptation of power.

For instance, Michelangelo’s Crucifixion of St. Peter (which is located in the smaller, private, Pauline Chapel, used as a private prayer space) is a gruesome symbol of the crucifixion of the first Pope. It’s not just decoration: it’s actually a caution to the cardinals and the Pope against the abuse of power. Remember, it says, that you are only a follower of God, not God himself.

Anyway, when the cardinals were doing their conclave three weeks ago, there was one very large painting by Michelangelo looming over them which might have influenced their voting. It’s a visualisation of what might happen to them in the afterlife if they make the wrong decision.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment is my favourite painting to explain to people for so many reasons. Not only is it a truly epic and monumental subject: but it’s also just an amazing feat of human creation. Michelangelo painted this 60-foot tall mural all by himself, in his sixties.

There is also just so much going on symbolically. Who’s who? What’s what? How are we meant to read it? And, crucially, how would we read it if we were looking at it for the first time, by candlelight, in sixteenth-century Italy?

Well, here’s how!

1. The Elect

All paintings have an entry point. You might think that when you look at a painting you take it all in at once, but that’s not quite true. Often our eyes enter a painting from the left-hand side, because that’s how we’re used to reading words on a page.

So, in this vast fresco, our eyes are ushered in from the bottom left. We begin with the reanimated corpses of the elect. These are the virtuous souls. They rise from the ground, having just been woken up by the loud, trumpeting angels in the middle of the painting. Some of the elect corpses don’t have any skin, so presumably they’ve been buried for quite a while.

Our eyes rise with these elect souls, several of whom are being dragged up by kindly angels. Michelangelo was one of the first artists to depict angels without wings. This is a facet of his so-called ‘Renaissance Humanism’: a philosophy and movement which advocates for the idealisation of the human body and mind. Michelangelo’s ‘Renaissance Humanism’ is also why lots of the figures here are naked.

3. The Saints

Eventually we reach the heavens, where a bunch of saints and apostles are standing on the clouds.

The saints are among the most fun things about the Last Judgment. This is because Christian iconography is a bit like spot-the-difference, or Where’s Wally.

Basically, saints always come with a motif — whether that’s a colour, or an object they hold, or how they style their hair — which helps us to identify them. Here, on the far-left: we have St John, with his camel-hair cloak, and St Lawrence, with his grill (Lawrence carries a grill because he was, unfortunately, barbecued).

In the middle we have St Peter, with the keys to heaven. Below: St Simon with his saw. St Catherine has her wheel, and St Blaise has a wool comb. St Sebastian — queer icon — always has arrows.

The real kicker here, though is St Bartholomew. He’s holding the flayed skin of Michelangelo himself. It’s a dark and humorous self-portrait by the artist… perhaps symbolising his fatigue after painting a 60-foot tall painting by himself!

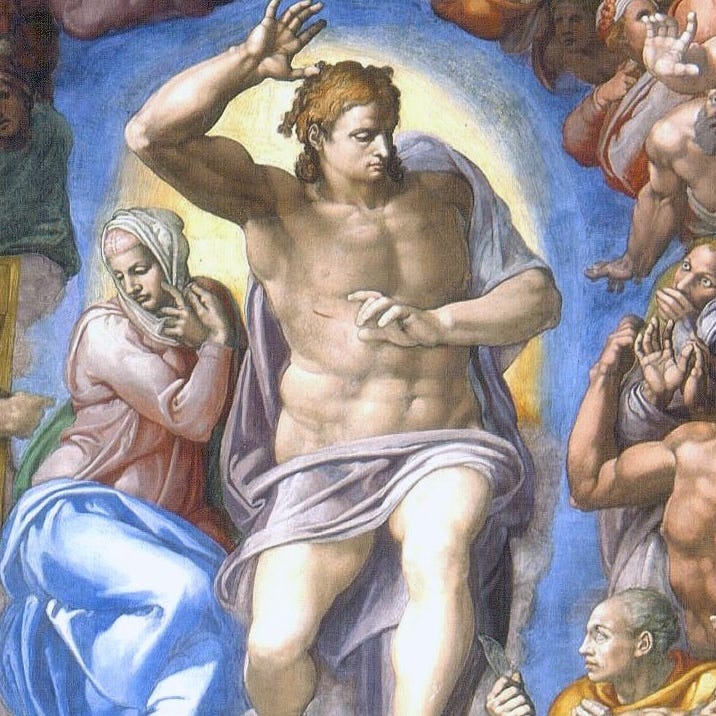

4. Christ

The spandrels (arches) in the upper-two corners contain the Crucifix, the crown of thorns, and the pillar upon which Christ was flagellated.

Not only do the spandrels contain important symbolic references to the Crucifixion but the positioning of the angels also directs our attention towards the main character of the painting: Christ.

Michelangelo’s Christ is controversial for so many reasons. He’s beardless and semi-nude. This is how we know he’s a quintessentially Renaissance Christ rather than a medieval one. The Renaissance (meaning ‘revival’) is all about the revival of Classical aesthetics and literature. Michelangelo’s Christ isn’t really a Christ at all: he’s an Apollo, a sun-god, and his only markers of Christendom are the stigmata (on his hands, feet, and side), and his long-suffering mother, the Virgin Mary, sitting next to him.

Another point is that this Christ, as Christs go, is extremely expressive. Christ is supposed to represent benevolence and sacrifice. This is why his expression is often neutral. However, here, Christ is active, wrathful, and his pose leads our eyes down into the bottom-left. His gaze falls upon the sinners who are being violently dragged down to hell — yikes!

5. The Damned

Now for the best bit.

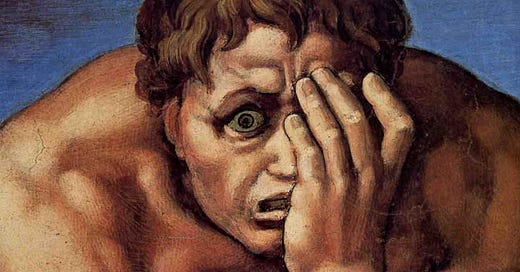

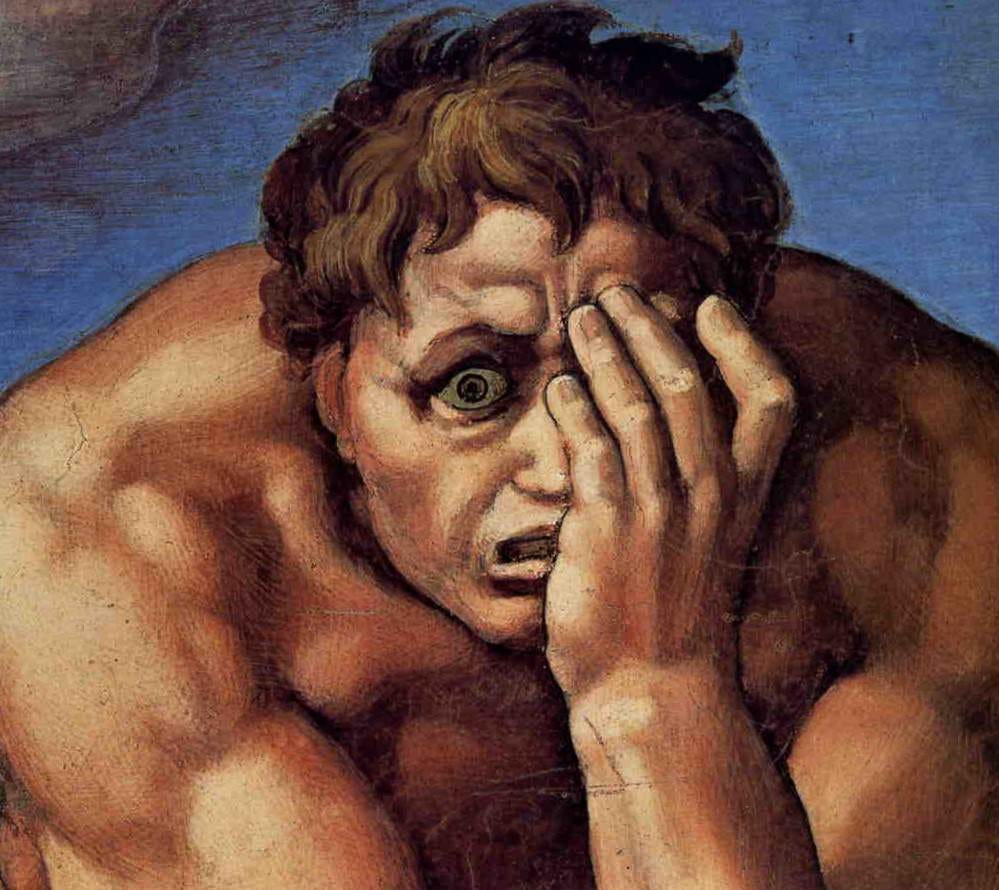

So, our eyes follow Christ’s and we fall upon the damned souls. Their contorted bodies invoke pain. One of them is being pulled down by his testicles. Another falls head over heels. Another is being bitten by a serpent: his eyes reflect the horror of eternal damnation. There are ghostly apparitions, devils, serpents, and bare bottoms.

Ferrying the souls across the river Styx is the mythological demon, Charon. He’s the one holding an oar. Charon is a figure from Dante’s Inferno, and not from the Bible. This was one of the many things Michelangelo was criticised for when the painting was revealed to the cardinals in 1541.

Finally, in the pits of hell, we glimpse the fire and brimstone which might await us if we stray from righteousness. The most abject of these figures is a man in the extreme bottom left. This is Minos. He has the ears of a mule, and his body is wrapped by a serpent.

The serpent is biting him on his… er... well, have a look for yourself.

Apocryphally, this man is a portrait of Biagio da Cesena: the priest and notary who was papal master of ceremonies while Michelangelo was painting the Last Judgment. Apparently, da Cesena was extremely shocked by Michelangelo’s depiction of nude bodies, and said that the fresco was a ‘dishonest display of shame’ better suited to a tavern, bar, or bathhouse than to a chapel.

Giorgio Vasari, the famous biographer of Renaissance artists, tells us that da Cesena had so displeased Michelangelo that, in revenge, he painted him ‘with a great serpent coiled around his legs among a mountain of devils’.

This is a case of Michelangelo playing God, a bit, isn’t it? Just as God might damn a sinner to Hell for transgressing, Michelangelo damns da Cesena (and who knows who else!) in his vision of the apocalypse.

***

And I suppose that brings us back full circle to The Creation of Adam again. In Christian doctrine, God is the creator of man. But man can also create things too. When God created man, he passed on a divine spark of creation, from the tip of his index finger, to man himself.

Michelangelo is here not just showing how man is subordinate to God, but also how man is a reflection of God. When he does or creates things he is partaking in the divine, because he is made in the image of God.

The point is that man has the choice to align himself with either the elect or the damned. Your fate isn’t ineffable: it’s up to you. That autonomy is God-given, but you choose where you land. It’s a relevant message even to those who don’t believe in the afterlife, though one which is doubtless more powerful to those who do.

In the highly unlikely event of my being invited to join a conclave, I’d definitely keep this message in mind when I was deciding on the next Pope. I wouldn’t want to make that decision for the wrong reasons.

All you have to do is look at Michelangelo’s damned man to feel a chill go down your spine.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

I say Dr Rebecca for Pope!

Wow, there is so much packed into this painting—and you walk us through it not only with tremendous knowledge, but also with humor and verve. It is virtually impossible to imagine how Michelangelo managed to pull this off, but of course, as you amusingly note, St. Bartholomew holding M’s own flayed skin gives us a good, solid hint how M himself must have felt!