In art-historical terms, I’m afraid size seems to matter a great deal.

Although (and here’s the good news) different sizes, shapes, and… er… degrees of rigidity have been preferred at different times in visual culture.

When perusing the Classical sculpture room at your local municipal museum, an indiscreet thought or two may have crossed your mind regarding the size of the exhibits. Those rippling, hyper-masculine or hyper-idealised bodies (think, Farnese Hercules, Apollo Belvedere, and Doryphoros) aren’t always entirely in proportion, and this is no accident.

Standards of masculinity were slightly different in Ancient Greece and Rome than they are now. By depicting the male body as strong and toned, and the male ‘part’ as small and restrained, the Classical sculptors were reflecting contemporary philosophical ideals. Culturally, it was significantly more important for a man to have big, throbbing intellectual faculties than to have animalistic, Priapic appetites. His smallness reflects rationality and self-control.

You get a similar sort of thing going on in the Medieval period – where the overlarge phallus is often tied to lustful sin or, more lightheartedly, to comedy and carnival.

But fast-forward to the Renaissance and you’ll find the complete opposite. Look, for instance, at the offensive protrusion in any painting of Henry the VIII. This is his ‘codpiece’: a highly fashionable male accessory, and a metaphor for his Kingly power, status, and virility. Throughout aristocratic portraiture of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, codpieces seem to have gotten bigger and bigger in a kind of willy arms-race. Mine is bigger than yours.

Though in the Baroque and Neoclassical revival, willies get smaller again, harkening back to the Ancient ideals. By the nineteenth century, Christian morality had made everyone so prudish that there’s no real nakedness to be seen anywhere, really – only fig leaves. With the exception of pornography, of course, which was absolutely thriving.

But what all of these art-historical phalluses across the ages have in common is a kind of erotic idealism. They aren’t tender and humane. They’re always the subject of masculinity, or of demonic lust: of grandiosity, theatre, violence, or bawdiness.

It took until the 1960s for artists to begin showing the human body with compassion: lumpy, bumpy, soft, tactile, and organic. And this is what the American art critic and curator Lucy Lippard, acentral figure in feminist art criticism of the 1960s–70s, meant when she coined the term ‘Abstract Erotic’.

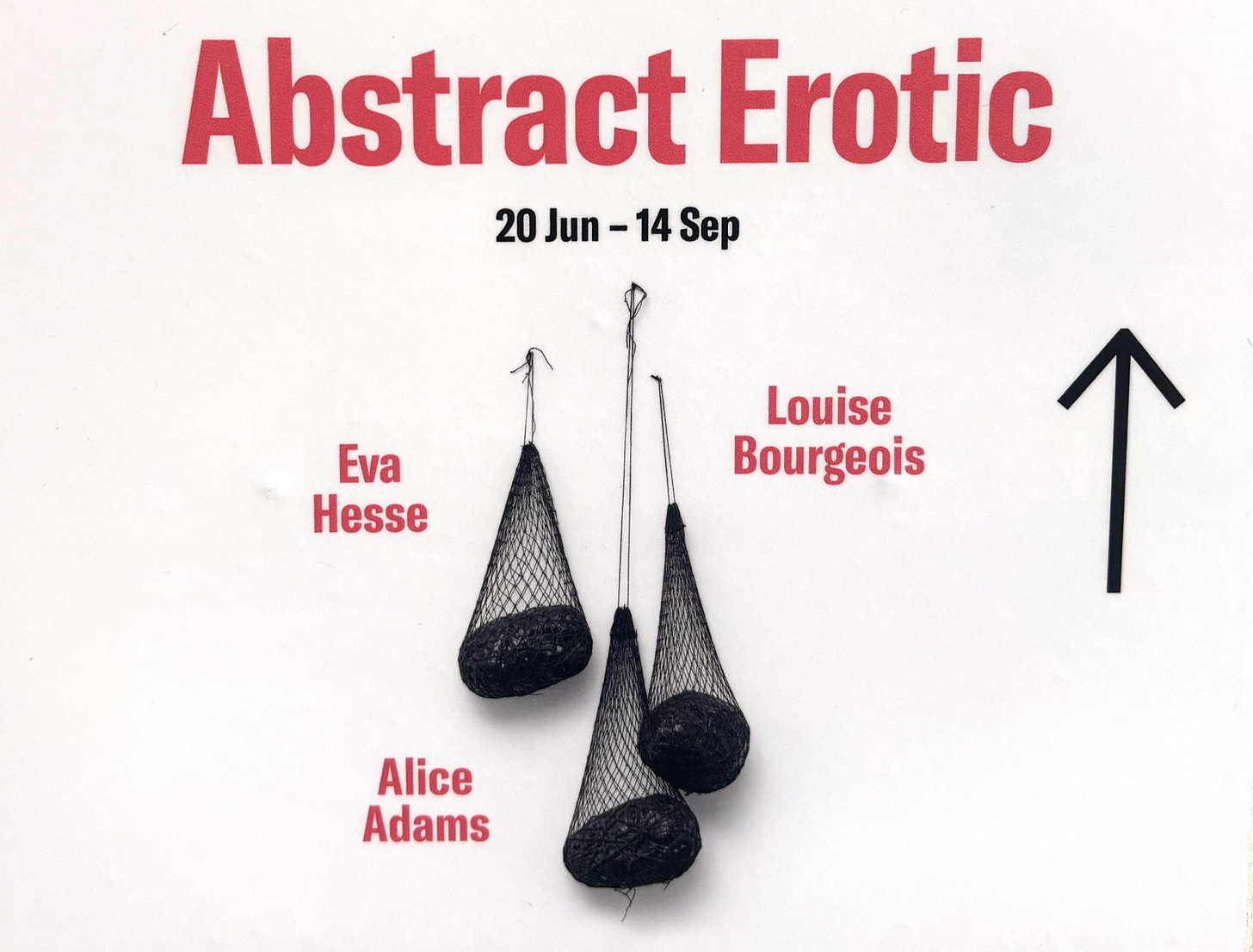

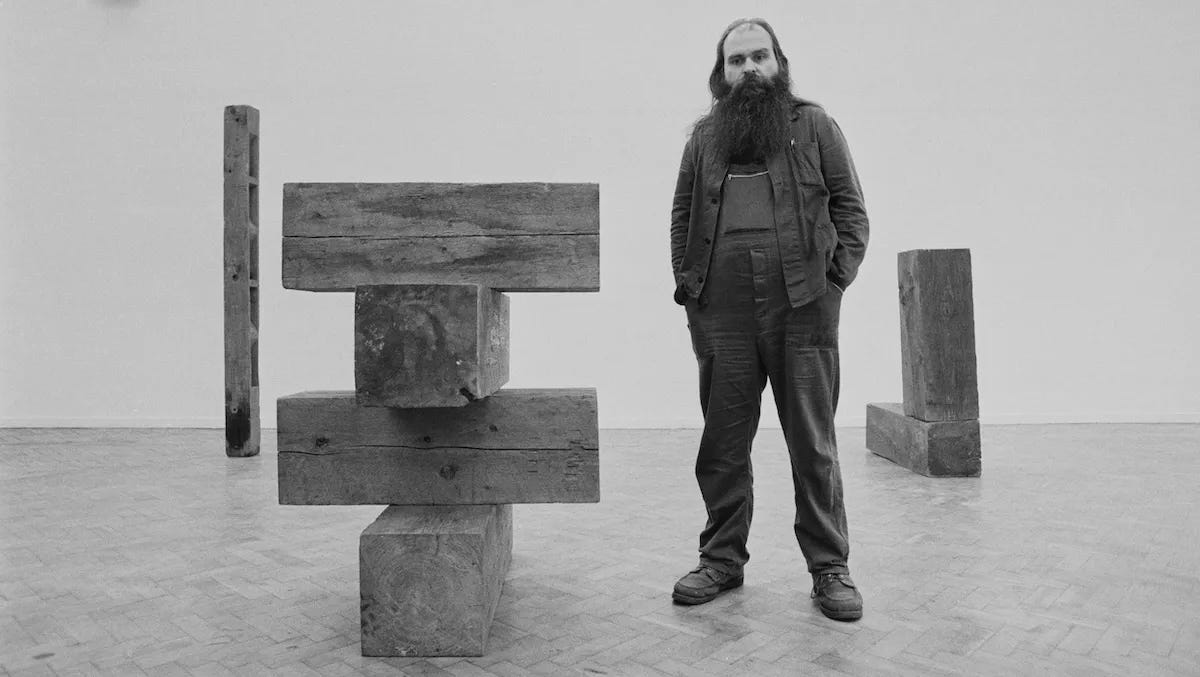

This is type of abstract and formally simple sculpture, with ‘rough edges’ and ‘erotic undertones’, which emerged in New York in the 1960s. There was something new and very feminist about it. Not only was Abstract Erotic pioneered by female artists – Louise Bourgeois, Alice Adams, and Eva Hesse – but it also subverted the clean, geometric, macho forms which had dominated abstract sculpture at the time: Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Tony Smith.

Abstract Erotic was the subject of an influential and radical exhibition, Eccentric Abstraction, which Lucy Lippard curated at Marilyn Fischbach’s gallery in 1966. The Courtauld’s latest show at Somerset House is an homage to this.

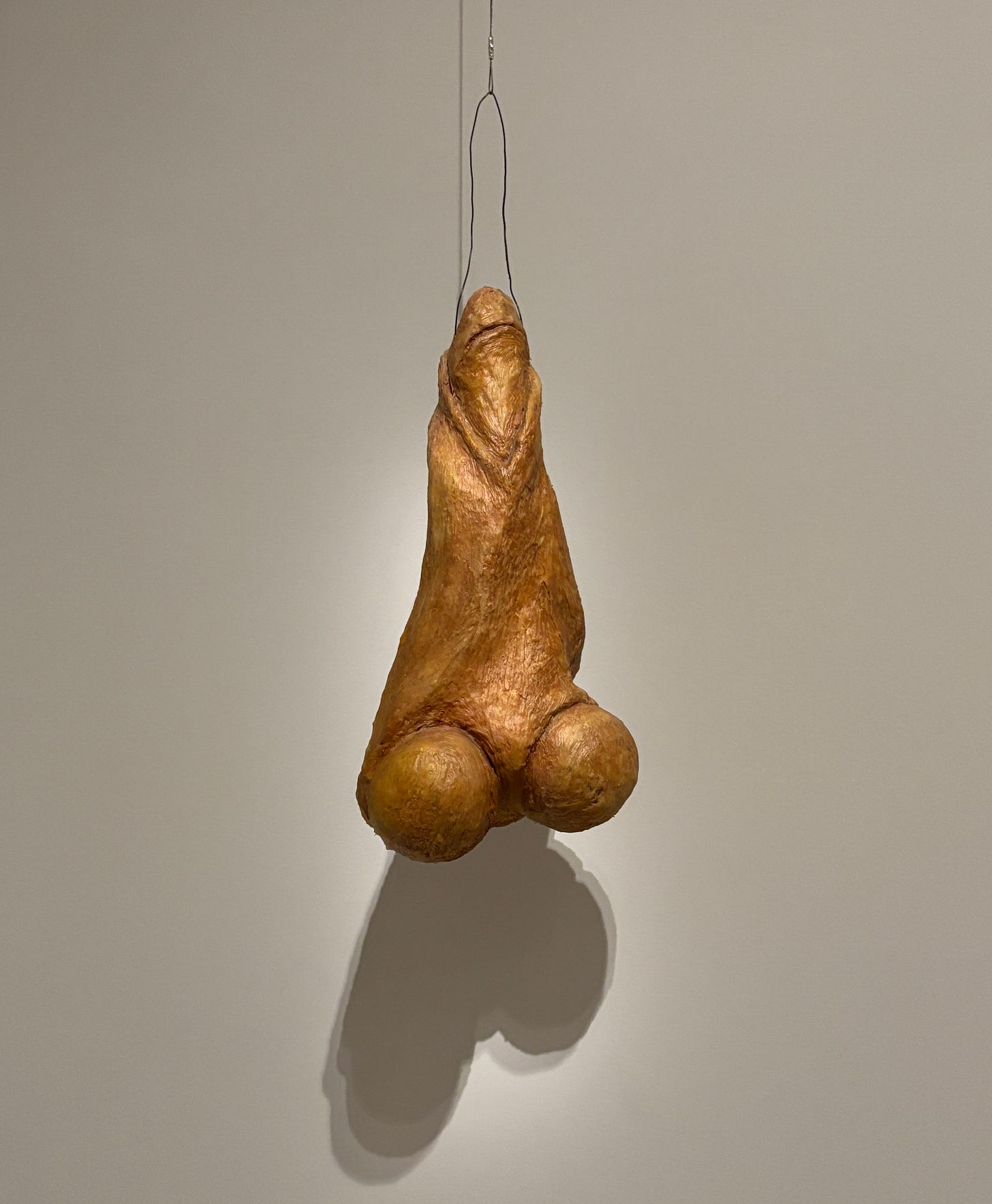

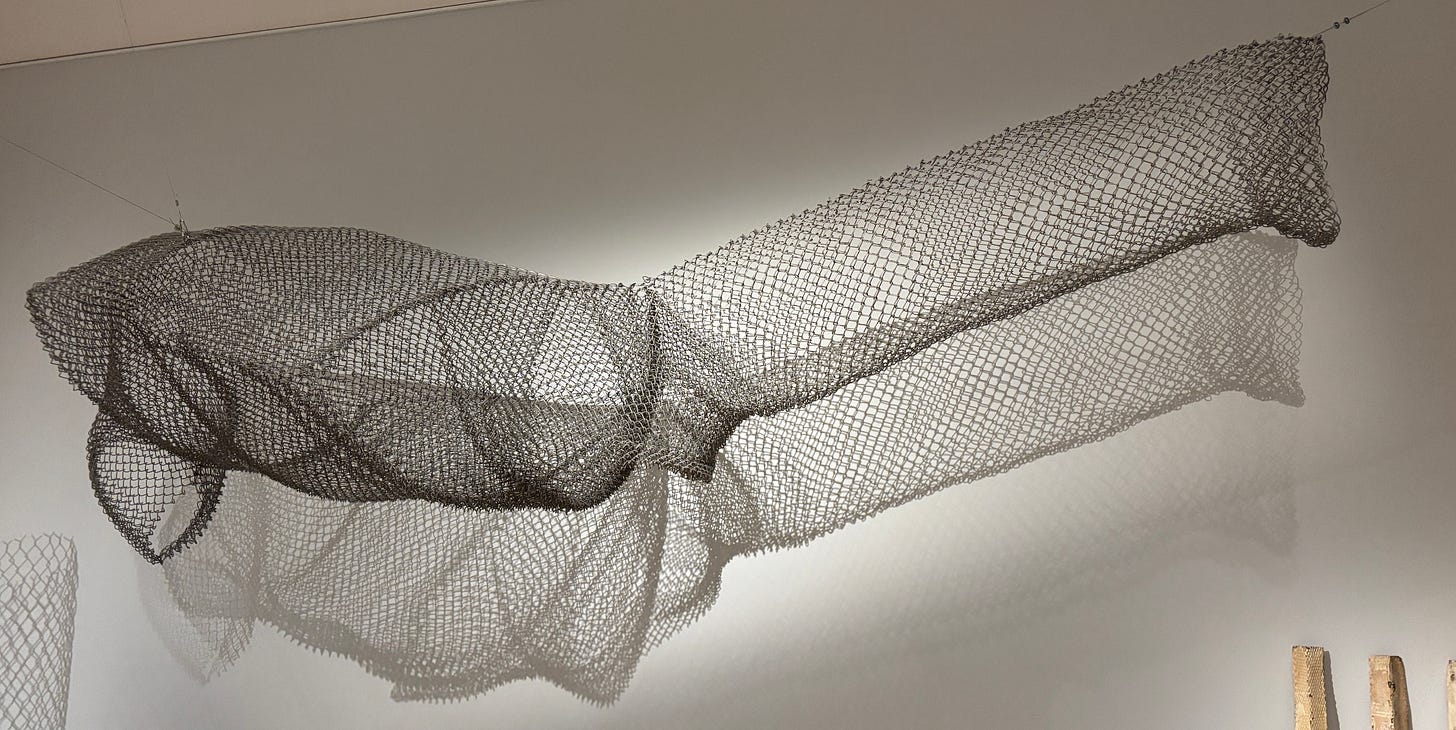

The Abstract Erotic sculptors approached the human body in a way that was less about ideal anatomy and more about the explicitly unideal reality of flesh. Their forms are intentionally ambiguous, indistinct, and absurd. They are minimalist, certainly: but they’re also clearly evocative of something human and sexual in their swelling, drooping, bulging, dangliness.

No Abstract Erotic phallus is absolutely, only that; it might just as easily be a cluster of breasts, or testicles, or potatoes in a sack. The point is that these sculptures deal simultaneously with the male and the female body, the erotic and the grotesque, and thus explode those rigid ideas of masculinity which the Farnese Hercules or Henry VIII’s portraits encode.

This is one of the reasons why Abstract Erotic is feminist: because it subverts patriarchal ideals of what the male or female body should look like, and instead points to something messy, fleshy, absurd, and wholly in-between.

Moreover, there’s an essential humour to these sculptures, operating as another form of feminist critique. There is something undeniably very funny about a big, drooping phallus named ‘Filette’ (which is French for ‘little girl’). There’s comedy in an artwork being called ‘untitled or not yet’, suggesting that the artist chose to title and not-to-title at the same time. There’s absurdity in the very fact of standing in a gallery, looking at a huge, shiny turd, with Van Gogh’s and Manet’s and Cezanne’s and Gauguin’s are hung just on the other side of the wall (note – all men).

A final, and pretty crucial, element of Abstract Erotic is the use of tactile materials. These aren’t rigid, permanent marble or bronze sculptures. Instead, they are made of malleable, sometimes perishable, things: latex, papier-mâché, chain-link, foam. The point is that these pliable objects invoke flesh, skin, hair, and bodily textures. Latex, in particular, can rot, darken, and become brittle over time. Like real skin.

It’s plain to see how Bourgeois, Hesse, and Adams paved the way for later feminist and body-focused artists, particularly the Young British Artists of the 1990s: Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin. Like their 1960s forebears, the YBAs took a grotesque and honest approach to the human form. Like Bourgeois, Sarah Lucas’ sculptures are a tangle of male and female body parts: noodly members, noodly tits – it’s all the same.

There’s something very liberating in that. No one looks at a Bourgeois or a Lucas and pontificates on the significance of the size of any of the body parts, because it’s not altogether clear what, or whose body parts are being shown to us. Instead, it’s all about ambiguity, softness, and the essential ridiculousness of asking whether size matters at all. We’re just lumps of flesh.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support my work, but can’t commit to a full-time subscription, why not leave a tip at buymeacoffee.com/theculturedump?

Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my TikTok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

That was very interesting, Rebecca, thank you! I saw Henry VIII's armour at the Tower of London years ago and was tickled by the size of his codpiece! Now I know!

I went to this exhibition last weekend, very intimate space. I also found the title Fillette so amusing! 😂