John Riordan is an illustrator and comic artist who lives in London. He is currently writing and drawing a graphic novel about the life of William Blake.

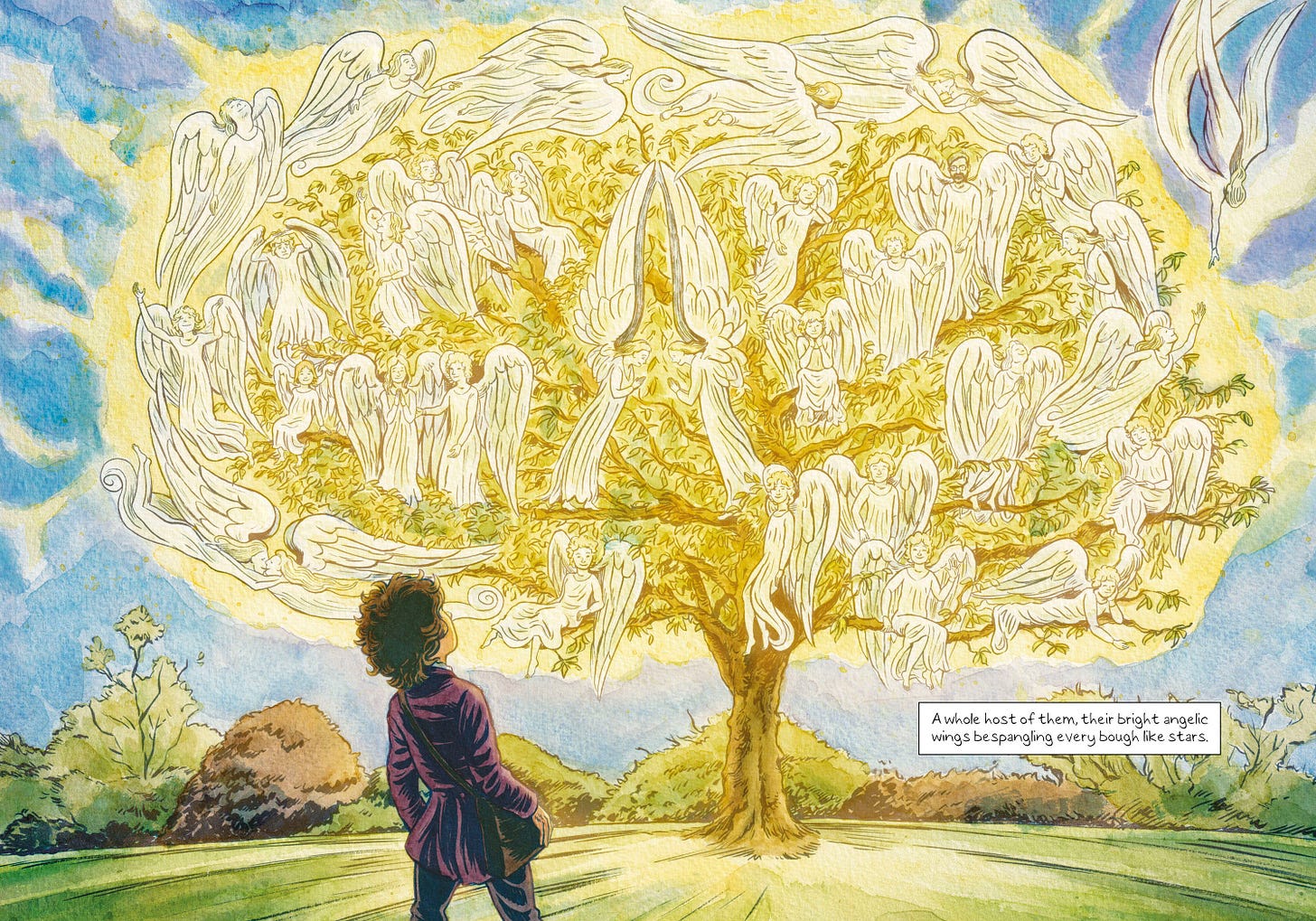

John’s studio is in Peckham Rye, just north of where Blake apocryphally saw a vision of a glittering tree, full of angels.

How did you come to illustration and graphic novels?

I’ve drawn comics since I was a kid. I think a lot of people stop reading comics when they grow up, but I never did. I studied English Literature at Balliol College, Oxford, graduating in ’99, but I was already doing freelance illustration soon after. It’s one of those rare things where, if people like what you do, you can get work without needing formal qualifications. Over the years, I’ve made lots of self-published comics while doing freelance print illustration.

Was it your literary background that drew you to the graphic novel format?

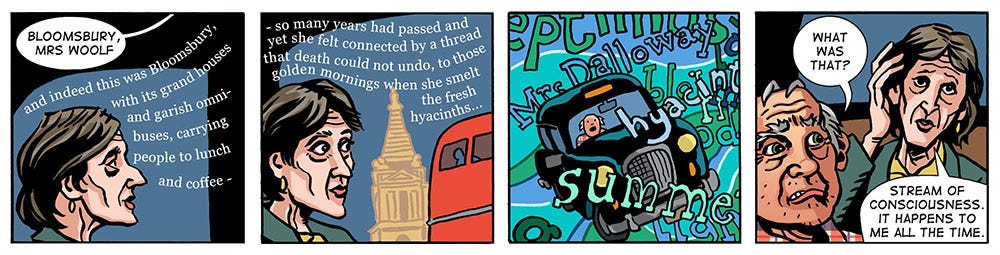

That definitely helped, but my love for comics predates university. It just always felt like a natural way to read and tell stories. The division between word and image has always struck me as strange… a kind of historical accident of print culture. Especially with Blake, I think the way the words and images interact — sometimes supporting each other, sometimes complicating each other — is really interesting.

So how did you first come across William Blake?

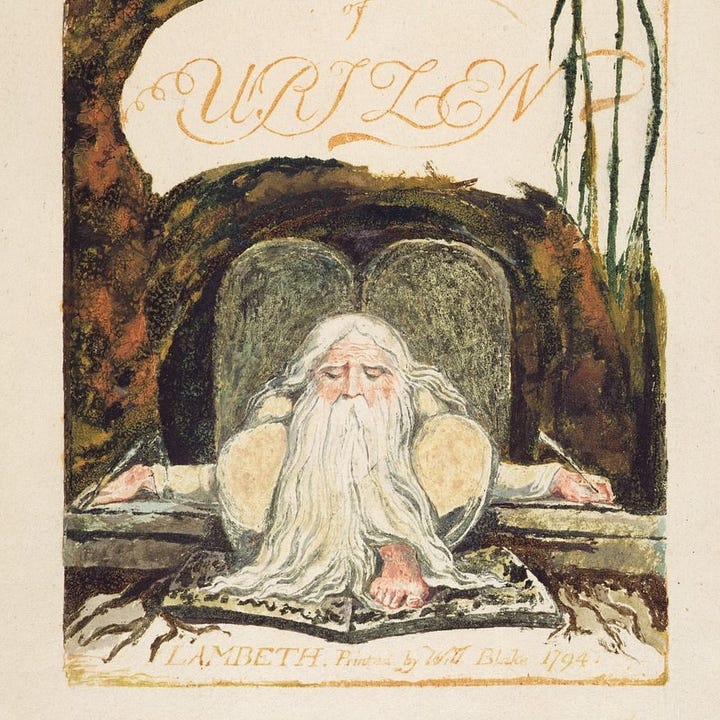

I think my mum got me into Blake, at least initially. And I very distinctly remember her saying that the ‘Old Testament dudes’ in Blake’s visual work — the God-looking figures with the beards — aren’t always necessarily the good guys. Which has always stuck with me. A very good early primer for Blake, I think.

My parents also subscribed to one of those serial art magazines, and we definitely had a volume on Blake. Around the same time, Peter Ackroyd’s biography came out. I won a school prize and used it to buy the book. My headmaster’s signed dedication is still in the front.

The other thing was music. Blur’s Girls and Boys had a B-side called Magpie, which basically lifts lyrics from The Poison Tree. It blew my mind that a pop band would quote Blake.

So those three things — my mum, Blur, and Ackroyd — got the ball rolling. And I’ve never really stopped being a bit Blake-obsessed since then.

When did you first think about making a graphic biography of Blake?

The idea’s been with me a long time. I used to do a comic strip for Time Out London called William Blake: Taxi Driver. It was this mad idea where Blake is reincarnated as a cabbie who sees all the times and periods of history in London at once. He picks up and drives around famous historical figures. That ran from around 2007 to 2009.

Then during my MA in Illustration at Camberwell, around 2011, I had the idea of doing a graphic poem about the contemporary financial crisis in the same way that Blake addressed the French and American Revolutions — by turning them into a kind of weird myth. The project was called Capital City. It was a sort of pseudo-mythological fever dream, which won an Association of Illustrators award.

It was around then that a neighbour — an English academic, eccentric, chain-smoker — said, “Why don’t you just do the Blake graphic novel?” I said that sounded impossible. And it is, in the sense of being a monumental amount of work. But the idea never quite left me.

So when did you actually begin?

I started when my daughter was little. She’s seven now. Once she was in nursery part-time, I had one day a week free. I could either send out cold emails to illustration commissioners, which always felt like sending messages into the void, or I could start researching this. I chose the latter. I started writing the script on 6 January 2021 — which is my birthday and also, bizarrely, US Capitol Insurrection Day.

What does a typical working day look like?

It depends a bit on what I’m doing. If I’m writing the script, I have to figure out which heavy books I need to take to the studio. Writing means organising a lot of information and then trying to get it down on the page.

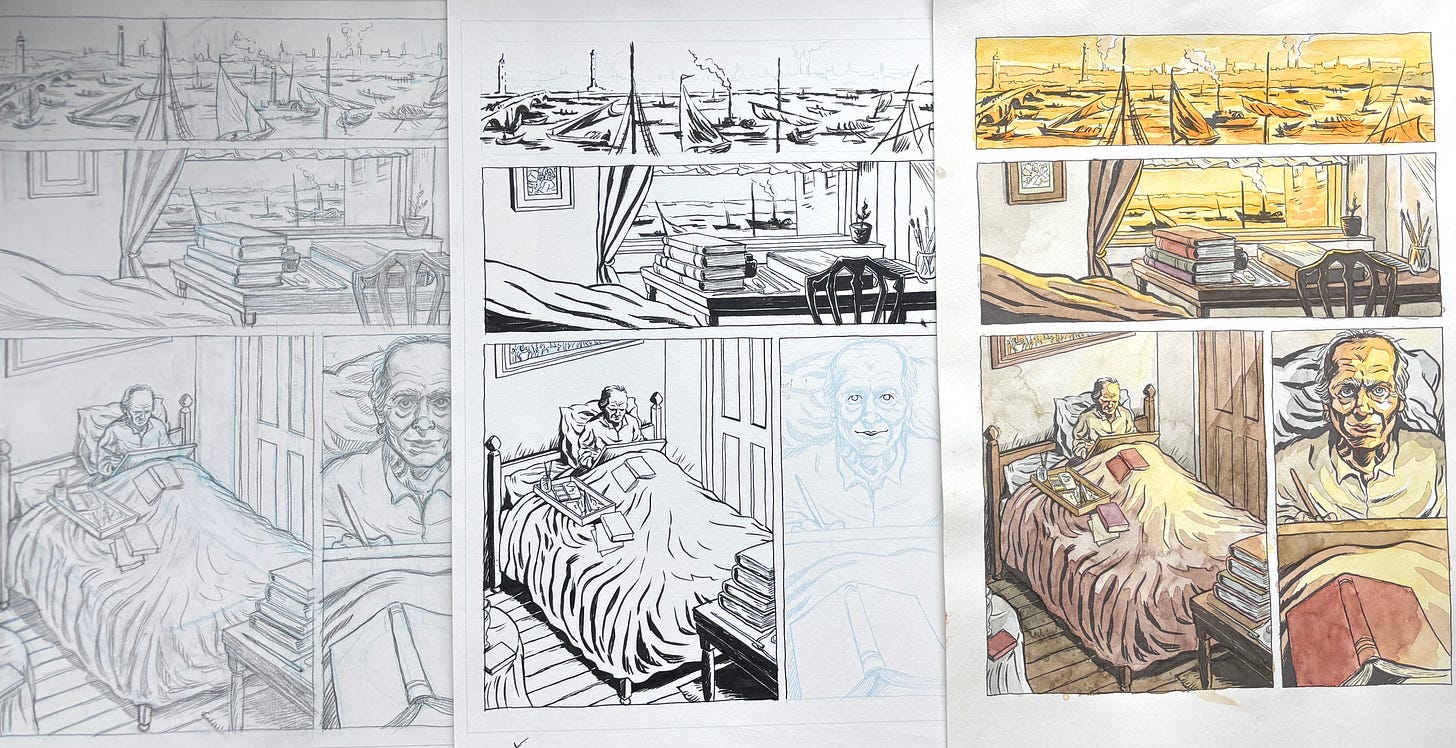

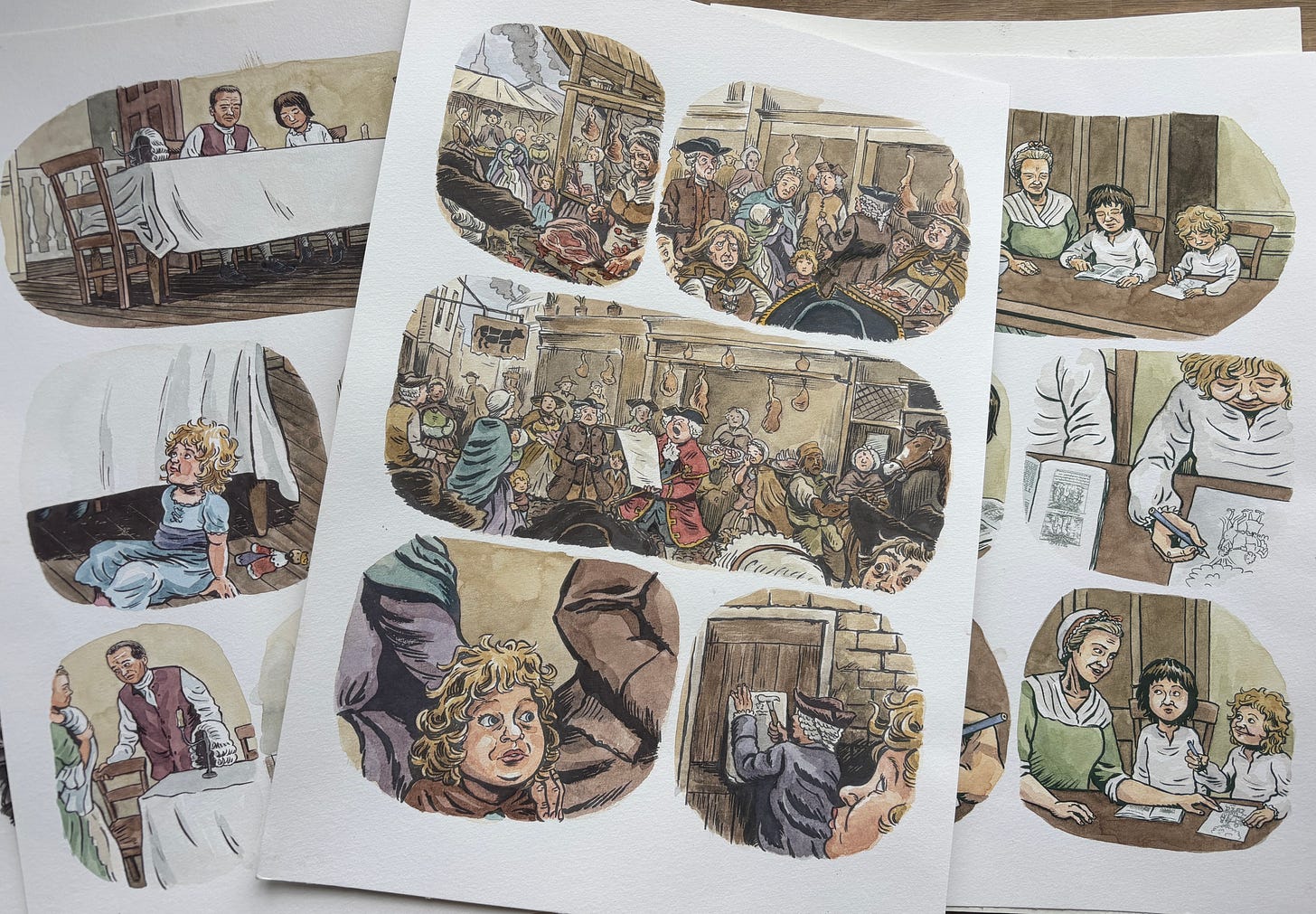

But if I’m drawing, the routine is more of a process. I’m quite old school, so it’s all on paper. First, I draw the design in pencil, then scan it into the computer. I print it out and ink on top. Then I scan that, print on watercolour paper, and colour it by hand. I’ll vary the colour scheme depending on what the scene requires.

I’m a bit of a perfectionist. My wife thinks I’m insane. And she’s probably right to some extent.

Do you use a Blake-inspired font?

Sort of. I created my own typeface based on my handwriting. The trouble with Blake’s actual handwriting (as opposed to his printed poetry) is it’s almost illegible. So my font isn’t a direct replica of Blake’s lettering, but I try to give it an organic feel. I prefer this because some modern comic fonts can look too digital and jarring. It sort of sticks out from the artwork.

You’re in an art shop — what are you buying?

Cold-pressed A3 watercolour paper works best, especially when printing inked outlines and applying watercolours on top. Shout out to Cowling & Wilcox in Camberwell.

Do you ever use specific Blake images within the story?

Yes, sometimes. There’s one early scene, for example, of a sort of cosmic foetus — inspired by the globes of blood and bodies forming in The Book of Urizen. It’s ambiguous: are we in the womb, or in some pre-material visionary space before William enters the world?

What visual references do you draw on?

Over time, I’ve built up a vast archive of stuff from exhibitions, books, and online. I categorise it by decade. So if I need a costume from the 1770s, I can just search for that. The irony is that Blake himself isn’t much help for depicting 18th-century life. His art is biblical, mythological. So for real London street life, I turn to Hogarth, Rowlandson, Gillray… artists who actually sketched the world Blake lived in.

How do you balance your own visual style with Blake’s?

I made a conscious choice not to mimic Blake’s style throughout — I’d fail, for one thing. His images aren’t really sequential, and they don’t read like a logical graphic narrative. They’re visionary, eternal, almost diagrammatic.

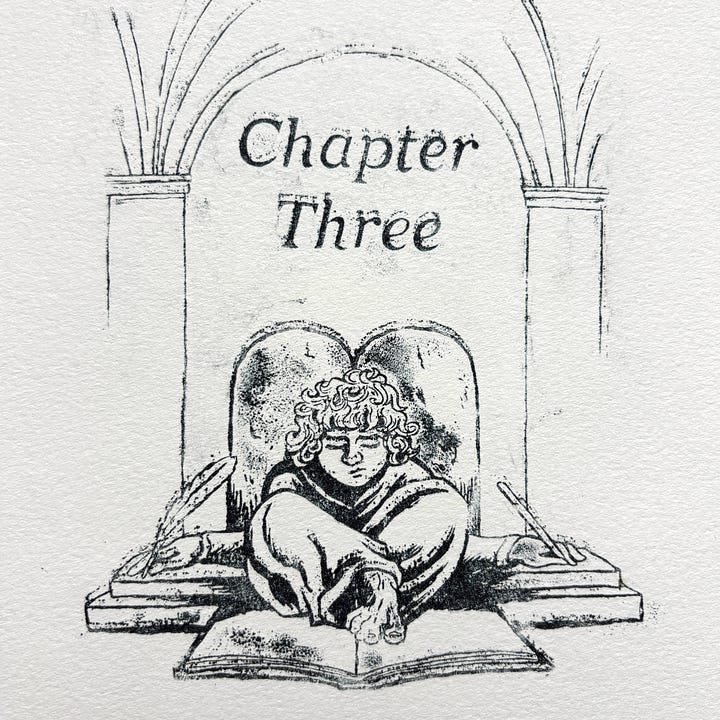

So instead, I pay homage in smaller ways. For instance, in the chapter headings, I made self-conscious imitations of Blake’s printed style. I drew the designs, then had them photo-etched on to copper plates. I then took them to Rice University in Houston and printed them myself on the replica Blake printing press that Michael Phillips had made for his exhibition at the Ashmolean in 2016.

Are there any particular works by Blake that really impacted you?

Oh God, like all of them.

I fell in love with Songs of Innocence and Experience as a teenager. They’re like brilliant pop songs — compressed, urgent, packed with imagery. London is still one of my favourite poems. It’s like Smokey Robinson meets punk protest. As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to admire the prophetic books too — Jerusalem in particular. Reading it is like taking a psychedelic trip: you don’t always understand it rationally, but it rewires your brain. The illustrations are mysterious, haunting, deeply strange.

If you could have a pint with Blake, what would you ask?

“What are you working on?” probably. He seems like someone who never stopped working. I imagine he’d be funnier and filthier than people think — I like the story of him and the painter Henry Fuseli trying to out-swear each other.

Has this project changed the way you see Blake’s — or your own — work?

Definitely. I’ve developed a new respect for his sheer output, and especially for the illuminated printing method. It’s so labour-intensive. Inking the plates, wiping them clean with cloths and cotton buds (which I’m pretty sure they didn’t have in the eighteenth century)… it’s meticulous work. The early pieces, like All Religions Are One, are tiny — barely bigger than a postage stamp — and he did it all in reverse, by hand. It’s astonishing.

As for my own work, I think it’s reinforced the need for bloody-mindedness. You just have to keep going. Blake’s a kind of patron saint of freelance artists. He’d probably be the patron saint of being a stubborn bastard as well. In fact, I think those two are one and the same.

And finally, where can people follow the project?

I post updates on Instagram and my website. There’s a 30-page first instalment available for purchase (you can buy it here). It takes Blake up to the age of four, and I’m planning on finishing this book when he’s about 30. So, you know — some of the way there...

Follow John on socials: website / instagram / bluesky

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

What a wonderful knowledge Riordan has of Blake. His "obsession" serves Riordan well. And as others remark here, his illustrations are marvelous.

It's delightful to know he's doing a graphic novel of Blake; it's a great way to make the artist more accessible, especially to young people who might not otherwise ever come across Blake.

Totally gree with Caroline, I could almost taste them:)