The term ‘female rage’ was first coined in its modern incarnation in a 1982 film studies essay by Lindley Hanlon, published in The Millennium Film Journal. While Hanlon was far from the first to point out that women feel anger in response to cultural oppression (the likes of Hildegard of Bingen, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Germaine Greer had pipped her to the post), she was the first to use ‘female rage’ in an art-critical context.

Female rage is more than just ‘women being angry’. It’s a political term which refers to a specific type of artistic expression of unapologetic defiance against the experience of womanhood, and specifically womanhood under patriarchy. Female rage in art is always symbolic of the wider plight of women, everywhere. Sexual violence, regular violence, childbirth, menstruation, bodily autonomy, freedom: these are the universal subjects of female rage.

There’s been a lot of internet discourse about female rage in the last few years.

Notable video essays by Alice Cappelle, Mina Le, and Final Girl Digital come to mind. Cinematic Montages of Karyn Kusama’s Jennifer’s Body (2009), David Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014), Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019), and Ti West’s Pearl (2023), beset to the tunes of Paris Paloma’s rousing ‘Labour’, or Mitski’s haunting ‘Abbey’, have spread like wildfire across Youtube.

The much-liked comments on these ‘female rage’ posts articulate feelings of solidarity, of intergenerational connection between mothers and daughters, of the burden of performing femininity. ‘Female rage. This is it.’, writes one commentator on Paloma’s music video, ‘Millennia of female rage condensed in a song’.

Other commentators spill their guts about trauma, mental and physical health struggles, finding, in this or that video montage, a validation of the internal suspicion that their struggles aren’t exclusive to them.

‘As a woman from Turkey, I know how you American women feel’

‘I feel so unbelievably understood right now’

‘Crying for my mother, my grandmothers, and my daughters that one day may be while listening to this song.’

Though much-aestheticised, female rage is not pretty. It can take the form of internalised misogyny, or violence against other women, or even children. In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, the Queen of the Goths, Tamora, orchestrates the violent rape and mutilation of the innocent girl, Lavinia. Another, earlier, example comes in the character Medea (from Euripides), who kills her own children to avenge her husband’s infidelity. Clytemnestra, another Classical female rager (from Aeschylus’ Oresteia) murders her husband, Agamemnon because he killed their daughter — and she’s damned vindicated.

Although these acts of female rage are revoltingly violent, in a perverse way, you also root for them. This phenomenon has been recently coined the ‘good for her’ effect. It describes our impulse to celebrate messy, grotesque instances of female revenge. Implicit in ‘good for her’ is the idea that these women – Medea, Clytemnestra, Tamora, Jennifer, Pearl, and so on, are not just angry women. These are all women who are angry in response to inherently gendered things which have happened to them.

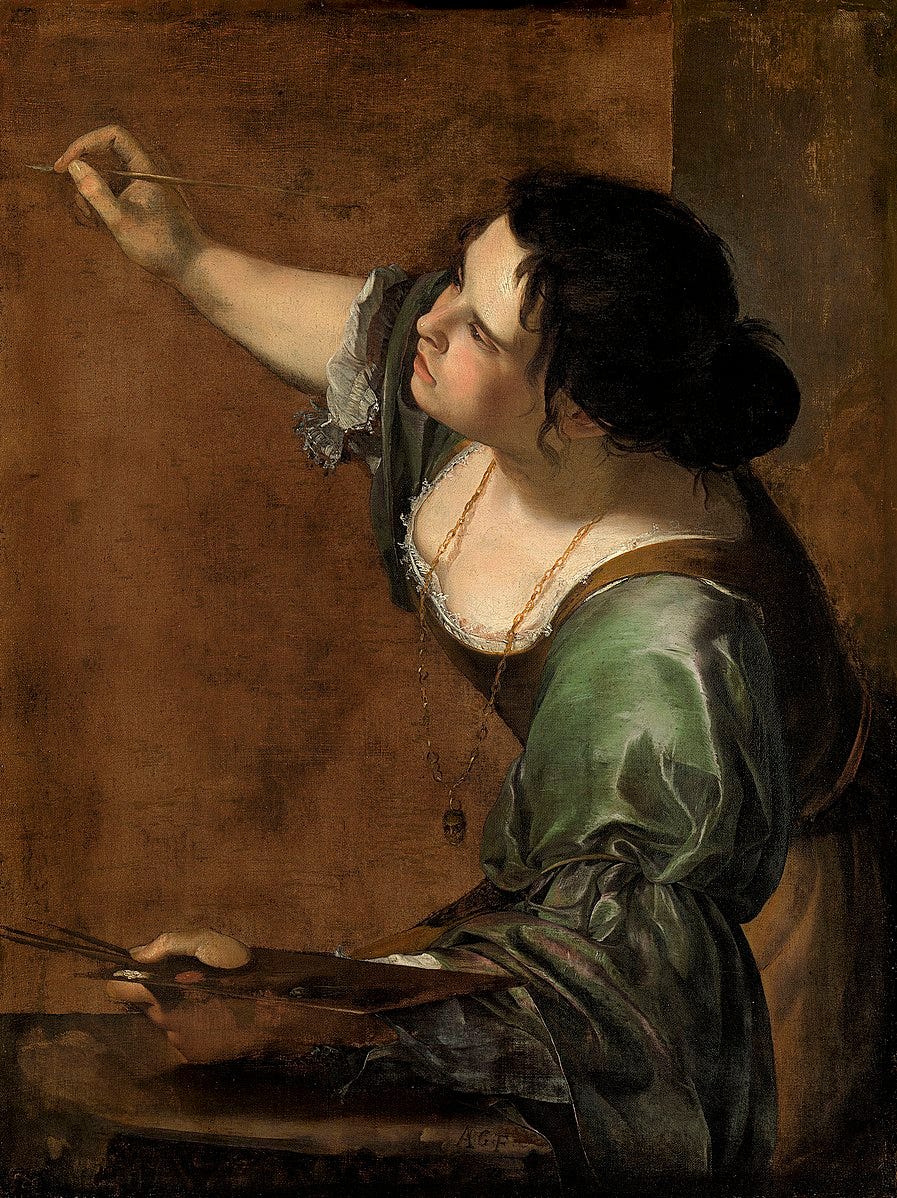

But there is no artist who embodies female rage more than Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656). A new exhibition of her work is about to open at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris.

Artemisia is one of the few women to have achieved international eminence among the Italian Baroque painters. She was the first woman to be admitted to the prestigious Florentine Academy of Arts and Drawing in 1616, having trained under the tutelage of her father, Orazio Gentileschi, a successful artist in his own right. Artemisia’s work is characterised by skilful, dramatic compositions, chiaroscuro (dramatic dark-and-light colouring), and masterful depiction of the female form. She gravitates towards female subjects.

You may have seen Artemisia’s Judith Slaying Holofernes before. It tells the story of Judith (from The Book of Judith), who frees the people of Israel by first seducing and then slaying the evil army general Holofernes, who works for King Nebuchadnezzar.

Artemisia’s painting is violent and uncomfortable — viscerally bloody, a tangle of limbs, and deep, dark colours — and it relates to Artemisia’s experience working as an artist in an industry which was, in the seventeenth century, exclusively populated by men.

You may also have seen a different version of Judith Beheading Holofernes by another Italian artist who influenced the Gentileschis: Caravaggio. Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading is also powerful, and perhaps more technically accomplished than Artemisia’s, but it’s nowhere near as active, violent, or shocking. It’s not female rage, it’s ‘angry woman’ — and that’s an important distinction.

In 1611, before Artemisia painted Judith Slaying, she was raped by the painter Agostino Tassi, a contemporary of her father’s. Assuming her rapist would marry her — thereby ‘restoring’ her honour in the eyes of society — she continued a relationship with him. However, when it became clear that Tassi had no such intention, Artemisia’s father pressed charges for the violation of his family name. An arduous seven-month trial ensued, during which Artemisia was tortured to provide evidence. While Tassi was eventually convicted, he was only imprisoned very briefly.

With this in mind, might we read Artemisia’s Judith Slaying in a different light?

Compare Artemisia’s Judith with Caravaggio’s.

It’s the same subject, but the expression is vastly different. Where Caravaggio’s Judith is tentative, standing far back from her victim — perhaps a little unsure of her transgression — Artemisia’s is utterly determined. She and her maidservant pin Holofernes to the bed, forming a claustrophobic pressure point of raw domination.

But Gentileschi’s Judith isn’t just enacting revenge on Holofernes… it’s a real-life reckoning against her rapist, Tassi, and all men like him. Gentileschi’s painting is quintessential female rage. Because it’s not just about an angry woman, but it’s an expression of one women’s anger for all women, and the fact that they have to suffer men like Holofernes.

This is why female rage is deeply tied to female authorship. Female rage is at its best when it’s authentically authored by a woman, because that authorship is an unmitigated expression of her experiences, rather than filtered through the gaze of a male director or artist.

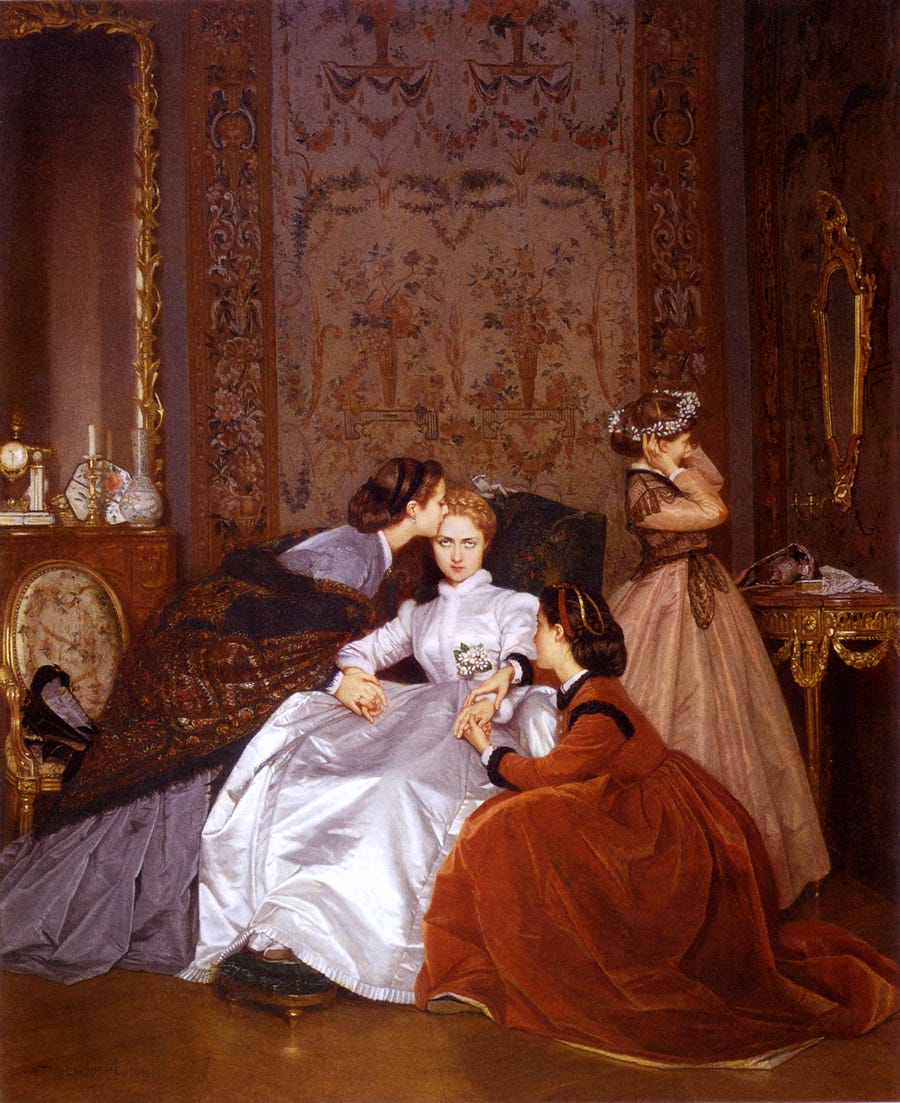

This is why I am wary of the video montages which include depictions of ‘angry women’ — for instance, Auguste’s Toulmouche’s Reluctant Bride, the Pre-Raphaelites’ various Clytemnestras, or even Ari Aster’s Dani (Midsommar) or David Fincher’s Amy Dunne (Gone Girl), because these are aestheticised male versions of female rage, which sort of misses the whole point.

This makes true depictions of female rage all the more difficult to come by in early modern and classic art, because women were not historically trained in the fine arts. Even if they were, there were often limits on what mediums women were allowed to work in or what images they not allowed to depict. If you’re interested in learning more about this, I’d recommend Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men (2022).

What makes female rage distinct from ‘angry women’ is the fact that it’s tied to a much wider issue. A woman’s anger can be resolved (Judith, for instance, can kill Holofernes) but female rage cannot. Female rage is innately connected to the experience of being a woman, and that’s never going away. So the famous quotation from Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag goes:

Women are born with pain built in. It’s our physical destiny — period pains, sore boobs, childbirth. We carry it within ourselves throughout our lives. Men don’t. They have to seek it out. They invent all these gods and demons and things so they can feel guilty about things, which is something we do very well on our own. And then they create wars so they can feel things and touch each other, and when there aren’t any wars, they can play rugby.

Judith beheads Holofernes, but the world does not change. Artemisia has achieved recognition in the canon of Baroque artists, but what about the thousands (hundreds of thousands? millions?) of female artists, craftswomen, artisans whose names have been lost to time?

In subject, execution, and authorship, Gentileschi’s Judith proves the enduring relevance and political importance of the fine arts — of art history — to stuff happening in the culture as we speak.

So, speak up. Happy International Women’s day.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions in London. I am also active on TikTok.

Judith Slaying Holofernes is possibly my favourite painting of all time and I get unreasonably excited when it pops up in my day to day life so thank you for writing this! I had the privilege of seeing the painting in person in the Uffizi in Florence a few years ago and I was totally spellbound by its brutality- that spurt of blood and the expression on Judith's face... *chef's kiss*. However, the true moment of female rage for me was watching all the other tourists walk right past Gentileschi round the corner to see Caravaggio's Medusa (1597). I couldn't help but feel that it was a particularly cruel curatorial decision to have such an emotive depiction of female vindication be overshadowed by the painting of a more famous male artist, the subject of which has now become synonymous with male violence against women. If they had been exhibited in reverse order the story would have been entirely different, and made considerably more sense, I think.

I think this is my favorite piece of yours yet! I love the connection you draw between the importance of female authorship in depicting female rage, and it was so cool to learn about Gentileschi! I hope this exhibit is still open this summer when I go to Paris!