Note: this article contains some explicit paintings, used for educational purposes. If that’s not your thing — don’t worry. Check back in next week for something more vanilla.

Question: what is more explicit than the full-frontal nude?

Answer: the full-frontal nude au naturel, with body hair.

I’m bringing this up because I’ve noticed an interesting phenomenon which has taken social media by storm. This is ‘Full Bush’ discourse: a catch-all trending title for the time-honoured debate over female body hair. ‘Bushtok’ consists of (usually) young women encouraging their contemporaries to eschew the razor, and it’s linked to a wider rejection of patriarchy, beauty standards, and a reclaiming of bodily autonomy.

All good stuff! But it’s worth pointing out that there is nothing especially new about this, and that the ‘Full Bush’ discourse is, in fact, deeply embedded in a rich, furry, and highly visual tradition.

A brief history of the bush

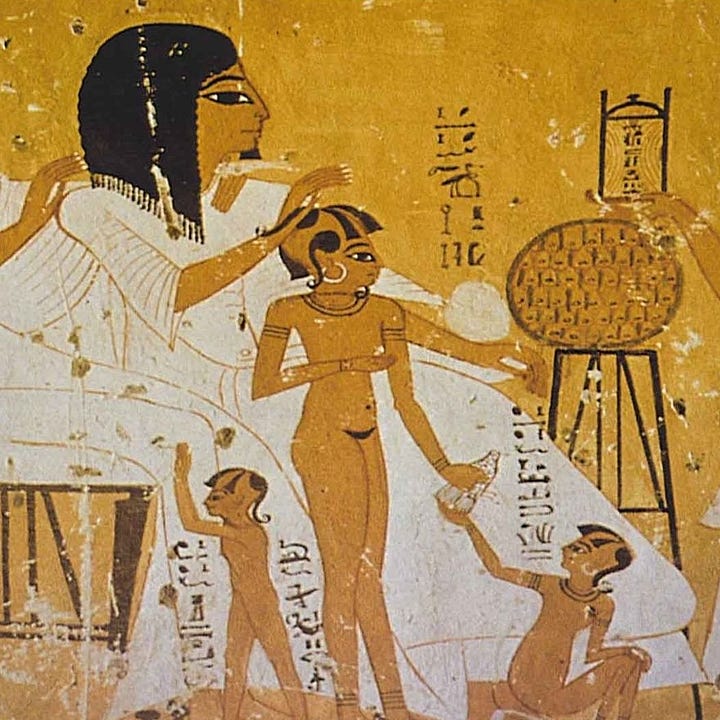

There is a misconception that the styling of body hair is a very new concept. It is not. Hair removal was practiced long ago in Ancient Egypt (3000 BC), Greece (800–300 BC), and Rome (500 BCE–476 AD), and during the Islamic Golden Age (700–1400 AD).

Depilation is mentioned in the writings of Aristotle, in Herodotus, in Ovid, and in Hadith literature. Aristophanes (Greek comic) makes jokes about women removing their pubic hair by singeing and plucking, in order to make themselves sexually attractive. In the ancient world hairlessness was associated with youth, beauty, and even with spiritual purity.

Instead of laser hair removal, though, the ancients used primitive razors, tweezers and even pre-modern depilatory creams made of animal fat, shells, bones, gum, and (of course) manure. If you’re interested in learning more about this, I’d recommend this article — or see the reading list at the end of this essay.

But the bush has not been out of fashion forever. We know that in Europe, during the Medieval period (so, broadly the 5th century to the late 15th century), Christian religious doctrine advised against hair removal, particularly for unmarried women or nuns. The idea was that the natural body was associated with modesty, humility, and the rejection of vanity; grooming, on the other hand, was a bit too ‘wenchy’.

This did not mean that female body hair was in fashion in the middle ages: on the contrary, it was sometimes considered a sign of voracious sexual appetites. Hairlessness was associated with virginal purity — but you weren’t really meant to remove hair either. Big double standards!

I would be loath not to mention ‘Hairy Mary’ (Mary of Egypt) — a saint who you’ll sometimes see depicted in Medieval manuscripts as completely covered in body hair. The hair represents her past life as a prostitute, before she got sainted.

Anyway, then we move from the Medievals to the Renaissance. Now, when you think of Renaissance nudes, like Botticelli’s Venus, you don’t really think of body hair. We might glimpse a whisper of the bush for instance, in Titian’s infamous Venus of Urbino, or in Dürer’s Adam and Eve (1504), but on the whole Renaissance nudes are basically hairless.

Why? Well, figures in Renaissance art are generally idealised representations of the body, based on (hairless) Greek mythological sculptures. In high art at least, female pubic hair was widely perceived as indecorous and, for lack of a better word, ‘un-ideal’.

The point is not that the bush was considered outrightly ugly in early-modern or modern art, but instead that it was considered too erotic, too powerful, and too much a reminder of our animal appetites.

My point is that throughout human history the bush has been a perennial battleground for politics, aesthetics, medical practice, and even religion to squabble over. It has been (and likely will be) styled and plucked and depilated in cycles.

But in art-historical terms, that battleground only really started getting really vicious in the nineteenth century, since this was the first time that artists dared to depict the ‘Full Bush’ in a more traditional painterly format, as opposed to in the sordid pages of a pornographic sketchbook.

And no one will be surprised to learn that it all kicked off in France.

Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine Du Monde (1866)

Paris in the mid-nineteenth century was a hotbed of frustrated artists. For a long time, their world had been governed by rigid rules about what to depict, and how to depict them. Any paintings that didn’t adhere to these rules would not be exhibited at the ‘Paris Salon’, which was the gallery where all the important artists showed their work.

Naturally, painters started rejecting these rules – and this eventually resulted in the Impressionist movement! Manet, Monet, Renoir… if you’re interested in learning more about this, I suggest you read this article.

One such painter was Gustave Courbet. He wanted to paint gritty, yet romanticised, visions of everyday people, and not the grand, mythological narrative scenes which the academic institution called for.

In the 1860s, Courbet, in line with his realist values (and also his proclivity for brothels), began painting a series of increasingly erotic works of women. This included Reclining Nude Woman (1862-3) and Sleep (1866). The pièce de résistance was his L’Origine du monde (1866).

This scandalous close-up of the female sex was commissioned by the Ottoman-Egyptian diplomat, Khalil-Bey, who was a prolific collector of erotic art. Sure, the painting is pornographic, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less significant. Painted by a successful academic artist, it enshrines the unshaven female body in the highest aesthetic terms.

The world, however, wasn’t quite ready for the full bush then. Allegedly, the painting may have been reported to the police when it was exhibited at a private dealership, behind a green velvet curtain, around 1889.

Now, at least, it’s on display in the Musee D’Orsay in Paris. Chouette!

Amedeo Modigliani’s Red Nude (1917)

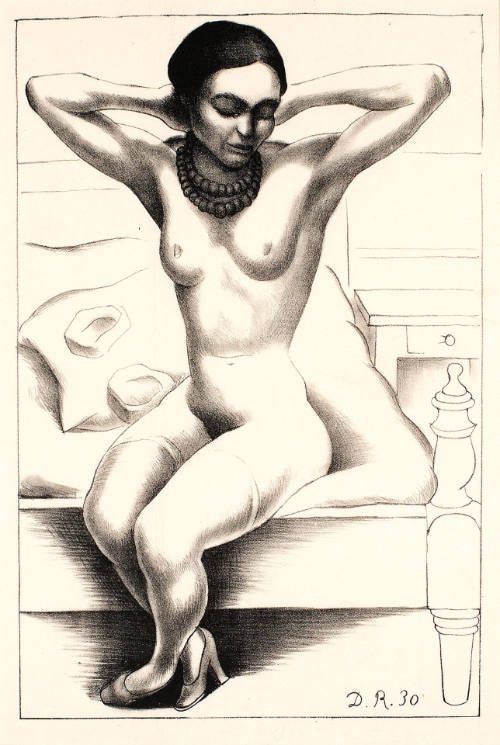

The second most famous instance of bush censorship relates to the post-Impressionist artist, Amedeo Modigliani. Modigliani achieved success as a central figure in the École de Paris scene around the turn of the century. His work has a highly distinctive, elegant, elongated quality, and he was a proud proponent of the erotic nude in both two and three dimensions.

His nude portraits are challenging and defiant. They feature women in confident, inviting gestures: their bodies open, warm, undulating and beautiful. They are highly stylised, with minimalist and slightly geometric faces which Modigliani adapted from masks and sculptures originating in West and Central Africa. These objects were then being brought into France via colonial trade routes, and they also influenced Picasso and Matisse.

Although Modigliani’s nudes are minimalistic — without shading, wrinkles, or musculature — they do possess body hair, and this hair is represented in an alluring, natural, and beautiful way.

In 1917 Modigliani held his first and only lifetime exhibition. It was a series of these languid female nudes. They aren’t pornographic, exactly, but they do teeter on the edge of the explicit — especially for the time!

What was problematic about the nudes was not their nakedness, but rather (you guessed it) the fact that this nakedness was too realistic. It was the bush! The bush was the offensive party!

And, anyway, because of their bushes, these paintings were famously removed from the gallery by an irate police officer.

Suzanne Valadon’s Adam and Eve (1909)

But if you’re looking for artistic works which really embody the feminist intent of Tiktok’s ‘Full Bush’ discourse, Courbet or Modigliani aren’t where you should start. Their works were painted for a male audience, and they visually market the female body — albeit a natural one — to the male gaze.

Have a look, for instance, at Suzanne Valadon’s Adam and Eve (1909). As a woman artist working in turn-of-the-century Paris, Valadon would have faced a potent cocktail of institutional sexism and limited access to professional training. Yet despite all of this she was the first woman painter to be admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and because of this, she brings an entirely different lens to the female nude.

There is a clear distinction between the power dynamics shown in Valadon’s painting, and those in Courbet’s and Modigliani’s. For instance: where there exists a voyeuristic and slightly dismembering quality to Courbet’s and Modigliani’s nudes (in Courbet’s we can’t see the face, and in Modigliani the legs are cut off), there is instead a completeness and visual harmony to Valadon’s.

Valadon here casts herself in the role of Eve, who is shown standing alongside her partner, Adam, represented by Valadon’s real-life partner, André Utter, who was also a painter. I read Valadon’s unapologetic depiction of her body hair as symbolic of free love and personal autonomy.

Originally both figures would have been nude, but the organisers of the Salon in 1920 where the painting was exhibited requested that Utter’s genitals be covered with fig leaves. This shows how female painters still faced a double standard when it came to depicting nudity in the 1920s.

While the female body (and bush) was permitted, the male was still off-limits…!

Frida Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital (1932)

Finally, we come to the patron saint of unapologetic body hair: Frida Kahlo.

Kahlo is possibly one of the most famous female artists of all time. Her unibrow and moustache are a defining feature of her self-representation. She paints in a folk-art inspired, dreamlike, allegorical style.

Disabled by a bout of polio she suffered as a child, and later severely injured in a bus crash, Kahlo’s art deals with intense themes: pain, violence, the body, death. In fact, her life was marked by extraordinary pain, and she transformed that suffering into some of the most powerful and personal art of the twentieth century.

Kahlo suffered several miscarriages, the amputation of her leg, marital abuse at the hands of her husband Diego Rivera, she was scrutinised for her associations with the Communist party, and she was constantly split between her birthplace of Mexico and the United States.

Her art explores womanhood, cultural identity, and the politics of disability. These paintings are often self portraits. In these self portraits Kahlo’s body is never idealised. It is variously surreal, bleeding, pregnant, broken, and yes — hairy.

Kahlo, like Valadon, doesn’t depict female body hair to provoke or allure (as Corbet and Modigliani did), but rather to represent the female body as it really is.

But for Kahlo, unlike for Valadon, the natural state of the female body is not a peaceful one. It is fundamentally related to pain — and not just the pain of womanhood (menstruation, childbirth), but also the pain of being a disabled woman, a displaced woman, and a woman unable to have children.

Kahlo’s self-portraits collapse the binary between private and public, turning even the most intimate or abject aspects of womanhood into symbols of resistance and, actually, objects of beauty.

That’s the long and the short of it

If the ‘Full Bush’ discourse which is happening on Tiktok right now feels revolutionary and liberating, that’s because it is: particularly in a digital world where we are constantly inundated with pornographic imagery of paradoxically hairless mature bodies.

But it’s a revolutionary and liberating discourse that has been going on for centuries, and which many brave women, and some priapic men, have trodden.

I’ve only mentioned two women artists here, but there is an ever-growing list of bush advocates in the contemporary art world: Jenny Savile, Sylvia Sleigh, Alice Neel…

So, ‘full bush’, ‘bush-in-a-bikini, ‘bush-in-a-thong’ — these phrases didn’t come out of nowhere. These debates have been going on much longer than we’ve been alive, and they’ll probably keep going on long after.

Just to reiterate: the question to ask is not whether or not a woman should keep her body hair, but we can ensure that she — and only she — dictates what she does with it.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Bibliography

Sandra Cavallo, Artisans of the Body in Early Modern Italy: Identities, Families and Masculinities (Manchester University Press, 2007)

Johannes Endres, ‘Diderot, Hogarth, and the Aesthetics of Depilation’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 38.1 (2004), pp. 17-38

Breanne Fahs, Unshaved: Resistance and Revolution in Women’s Body Hair Politics (University of Washington Press: 2022)

Rebecca M. Herzig, Plucked : A History of Hair Removal (New York University Press: 2015)

Amelia Jones, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts (Routledge: 2012)

Martin Kilmer, ‘Genital Phobia and Depilation’, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 102 (1982), pp. 104-12

Mireille M. Lee, ‘Body Modification’, Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece (Cambridge University Press: 2015), pp. 54-88

Mandy Richter, ‘To Show or Not to Show? Marcantonio Raimondi and the Representation of Female Pubic Hair’, in Indecent Bodies in Early Modern Visual Culture, edited by Fabian Jonietz, et al. (Amsterdam University Press: 2022)

It is remarkable how much dangerous power societies have managed to imbue into something so natural and intrinsically amoral!

And what an acknowledgement of weakness - how confident can you claim to be in the strength of the moral order you've created if you really believe that some public hair might send it into a death spiral of decadent degeneration...

Really fascinating stuff. Made me think of Effie Gray “He imagined me quite different from what I was” John Ruskin’s idea of the female body being based on Greek statuary. He couldn’t bring himself to touch her as nature made her

.