The Best Artists Copy Each Other

‘Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael’ at the Royal Academy (Nov 24 - Feb 25)

When I started learning about Art History, I was appalled to find that no work of art exists in a vacuum. I vividly remember a teacher rifling through exhibition catalogues, pointing at reproductions of the old and modern masters. ‘Look here!’ he said, ‘it’s all copies. Without Greek sculpture, there’d be no Roman copies. Without Roman copies, there’d be no Michelangelo. With no Michelangelo, there’d be no Raphael. What would the Pre-Raphaelites have called themselves if there was no Raphael?’ And so on and so forth.

Many years later, I came across a quotation from William Blake that hammered the same point home, and it’s stuck in my head ever since. ‘The difference’, Blake writes, ‘between a bad artist and a good one is that the bad artist seems to copy a great deal: the good one really does copy a great deal.’

What did Blake mean by this? Could it be that there’s a right way for an artist to copy and a wrong way? Bad artists merely ‘seem’ to copy, focusing only on surface details. Good artists, on the other hand, ‘really’ copy. For them, copying is an active, thoughtful process: a means of absorbing deeper principles that they can creatively reinterpret, over and over.

When looking for ‘good’ artists, you could do worse than to land on the High Renaissance greats: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael Urbino. Coincidentally, these artists were also exceptionally skilled at copying: and not just copying, but also absorbing, translating, reframing, and reinvigorating each other’s works. In fact, that’s what the exhibition I’m reviewing today is all about.

The Royal Academy’s latest show, ‘Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, c. 1504’, curated by Per Rumberg (National Gallery), is a meticulous, elegant study of ‘good copying’. It’s a snapshot into a critical year in Western Art History, 1504, when visual dialogue between these three masters was at its zenith. This was the only time that all three overlapped in Florence — and what a productive year it was!

In 1504, Leonardo was 52, Michelangelo was 29, and Raphael was 21. Leonardo was already an established master, Michelangelo a rising star, and Raphael just a student. How did Michelangelo impact Raphael, and in which artworks? Did Leonardo influence Michelangelo’s techniques, or the mediums he used? Did Michelangelo have any effect on Leonardo’s approach to disegno (the unified process of drawing and designing)?

The answers to these questions are hard to pin down, but this exhibition revels in the nuanced spaces between them. Interestingly, while this show ostensibly focuses on instances of visual quotation, it also highlights the three distinct identities of these artists. Michelangelo’s drawings are bold and precise; Raphael’s are light, empathetic, and sensitive; Leonardo’s are deeply emotive. Each holds his own against the others.

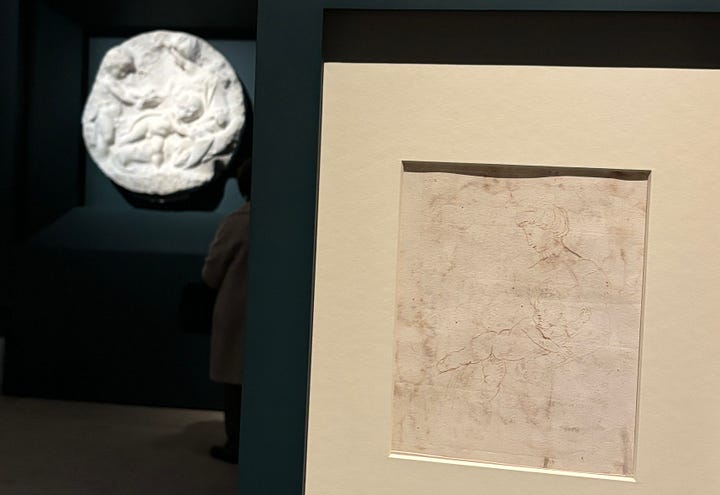

The opening room centres around Michelangelo’s beautiful rondel relief sculpture, the Taddei Tondo (a treasure of the RA collection), and Raphael’s drawings of it. Although we often think of Raphael as a direct contemporary to Michelangelo and Leonardo, in this period he was little more than an enthusiastic pupil. Raphael was not a Tuscan native (he came from Urbino, about 100 miles further east) but, upon hearing that Michelangelo and Leonardo were both working in Florence in 1504, he resolved to go see them in action.

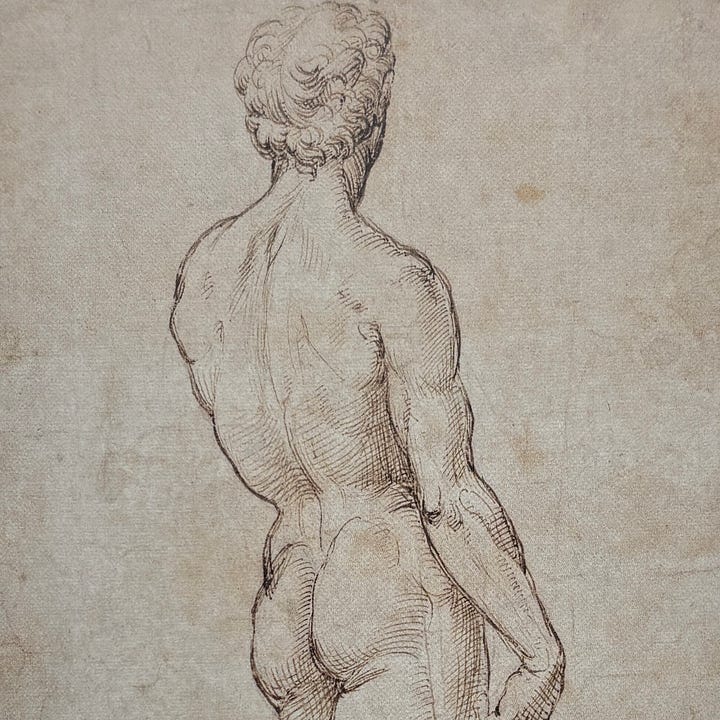

While in Florence, Raphael made studies after the David, Leonardo’s lost painting, Leda and the Swan, and also Michelangelo’s Tondo. These copies are the focus of the first section of the exhibition, and they are a great introduction to the ways in which Raphael assimilated technical principles from his elders, and made them his own. One lovely touch is that Raphael’s sketches are placed directly in front of Michelangelo’s Tondo, allowing us to view them simultaneously. Via this direct comparison, we can clearly see how Raphael interprets his sources — his sketches are graceful and spontaneous, yet they maintain the assuredness of the originals.

Thereafter, we’re shown some finished paintings by Raphael (like his Bridgewater Madonna) in which he reworks that earlier motif of Michelangelo’s elongated, twisting Christ child (from the Tondo). Raphael certainly brings his own flavour to this composition, changing the poses, iterations of the figures, and their gestures, bringing a characteristic empathy to the design.

Moving past Michelangelo and Raphael, we’re ushered into a dimly-lit passageway between the two large exhibition rooms.

This corridor is actually a key part of the exhibit, dedicated to one breathtaking drawing: Leonardo’s Burlington House Cartoon (1503-19). Surrounded by elegant, dark-green walls and low lighting, this work has a luminous quality. It almost looks as if it’s lit from behind. This effect is achieved through Leonardo’s masterful use of charcoal and white chalk. The overall effect is tender, uncannily lifelike, and — for lack of a better word — shiny, with a texture like satin or pearls.

This piece demonstrates the pure power of drawing. With colour stripped away, we’re left with the pure linear design. This is the only large-scale drawing by Leonardo which remains in existence. It might have originally been intended for an altarpiece in Florence’s government building, the Palazzo Vecchio.

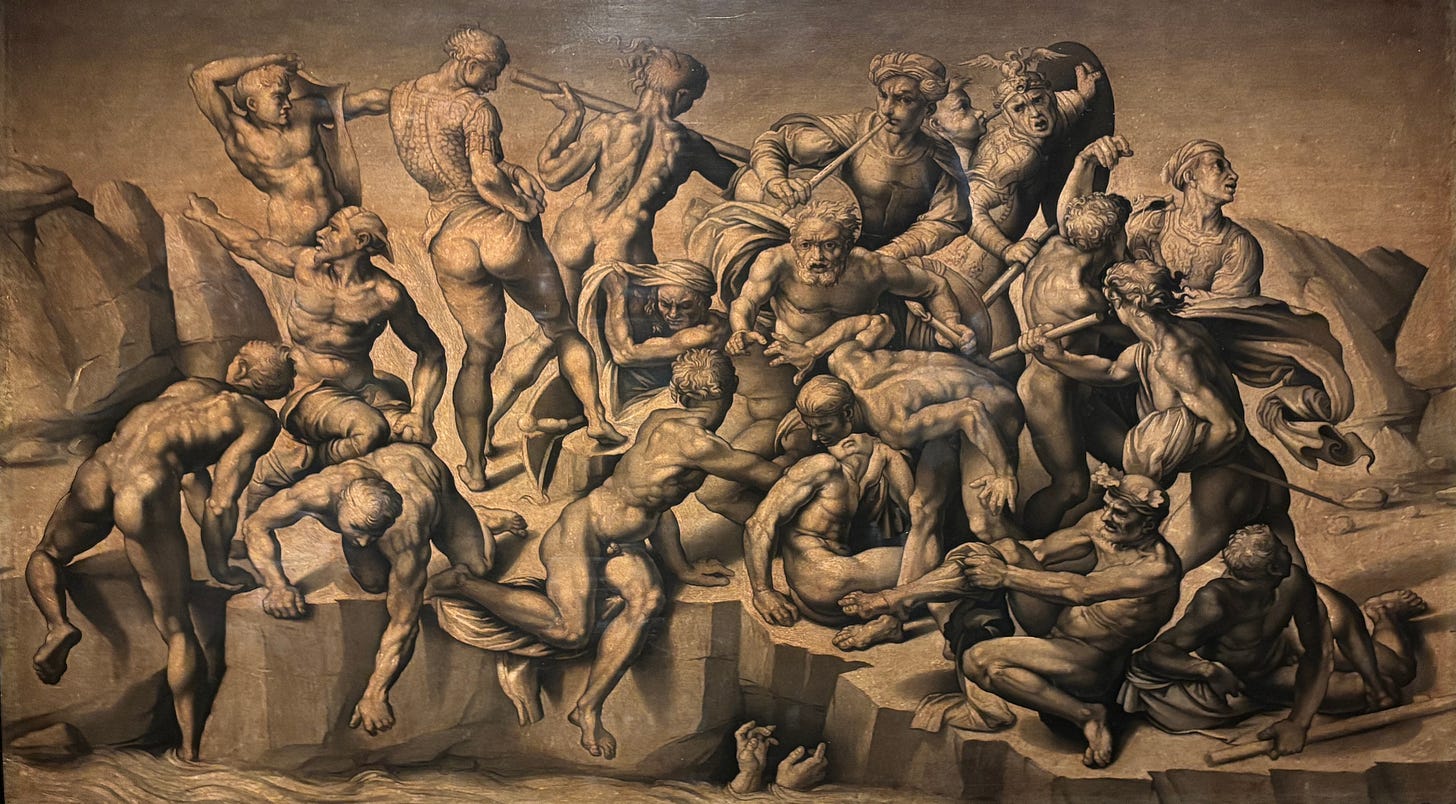

Coincidentally, Leonardo and Michelangelo were, at the same time, working on two huge murals in the Palazzo Vecchio. This leads nicely onto the next room, which is all about these murals: Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina and Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari. Unfortunately, neither was ever completed, and the preparatory drawings (cartoni) do not survive. However, we know what the designs may have looked like from surviving fragments, drawings, and printed reproductions.

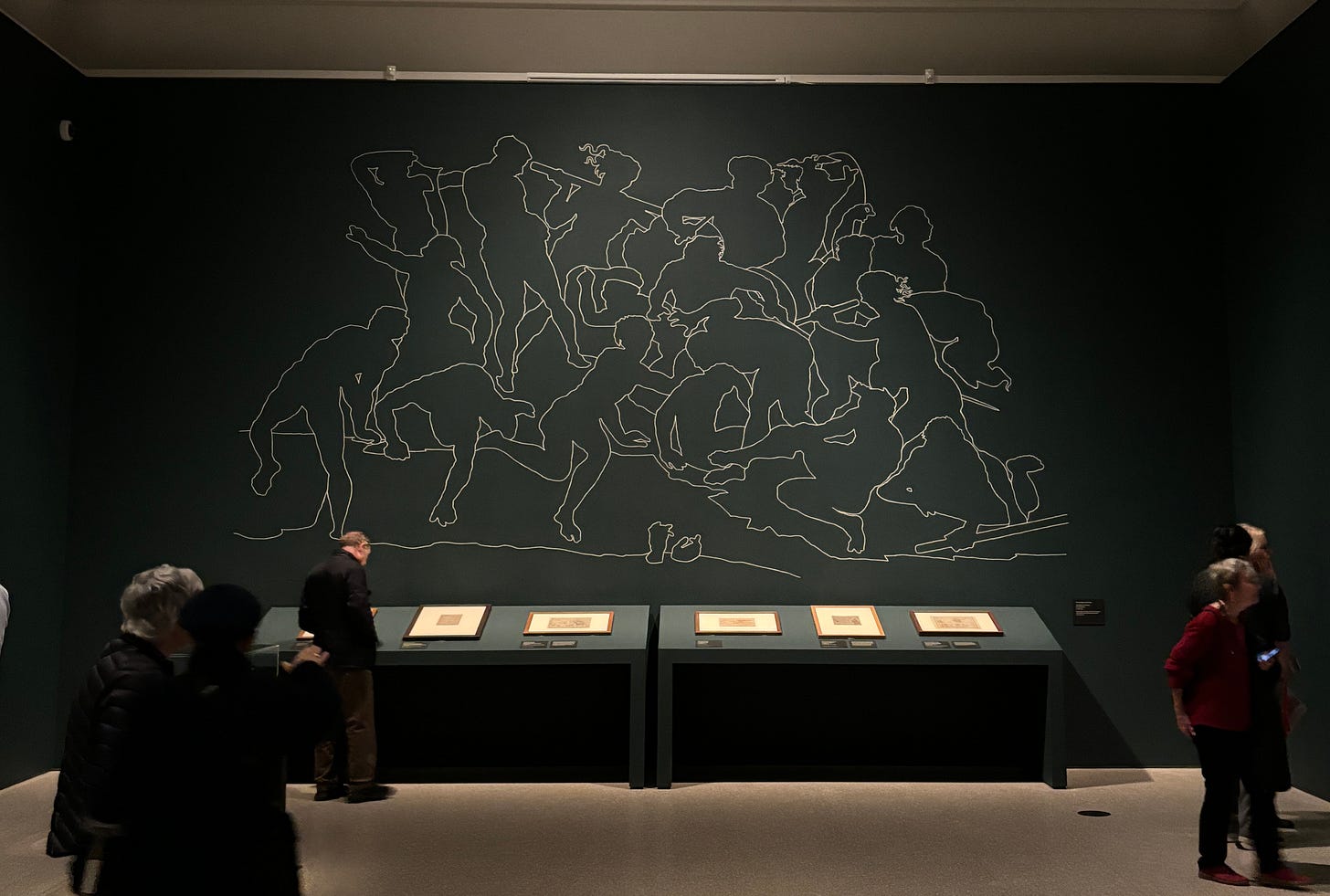

A cool feature at the end of this room (the first thing you see as you enter) is a giant projected outline of Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina. Had the work been completed, it would have been about this size, with large, muscular figures of the same scale as those in his Sistine Chapel (that is, monumentally big).

This final section explores the mythological rivalry, or ‘strong resentment’ (‘sdegno grandissimo’), between Michelangelo and Leonardo. Apocryphal anecdotes recount their mutual dislike of one another. Michelangelo, for instance, allegedly mocked Leonardo for not completing his projects; Leonardo, in kind, dismissed Michelangelo’s David, and suggested it be placed under the eaves of Florence Cathedral (the Duomo), rather than in a more prominent, open location such as the Piazza della Signoria.

Because of this rivalry, the fact that Michelangelo and Leonardo were commissioned to paint competing murals in the same space, at the same time, has fuelled much art-historical intrigue. But, their proximity may have also led to mutual influence! Leonardo, for example, observing Michelangelo’s mastery of anatomy, might have been inspired to focus more on drawing body parts. Michelangelo, noting Leonardo’s use of black (rather than red) chalk, may have adopted the medium himself. These changes, though subtle, remain significant.

In terms of the artworks shown here, the two standouts are the full copies of the completed cartoni. The first, Leonardo’s Anghiari, is drawn by an anonymous Italian artist and retouched by Peter Paul Rubens. This apocalyptic battle scene is a tangle of horses and men, filled with rage and movement.

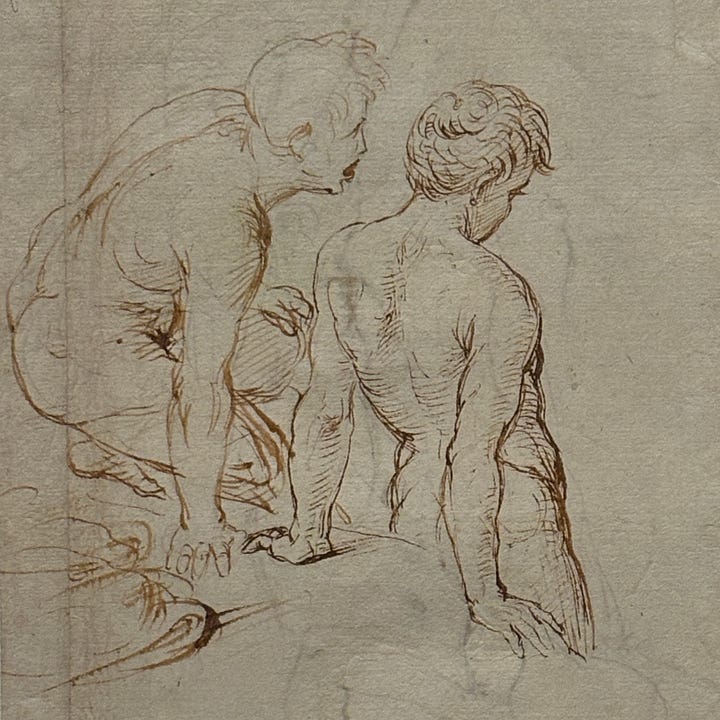

The second is Michelangelo’s Cascina, reproduced by another Renaissance Italian artist, Bastiano da Sangallo. This picture is sometimes referred to as Michelangelo’s ‘Bathers’, and it’s clear to see why. A group of denuded men clamber in and out of a river, competing for space. It’s an intense study of foreshortening, muscles, and anatomy. The design is replete with the blocky, weighty rhythms that characterise all of Michelangelo’s works.

We must remember, however, that both of these copies are mediated versions of the original large-scale drawings and are not by Michelangelo or Leonardo themselves. They are no substitute for the real things, but the real things are lost to time. At the very least, we can get a sense of the general stylistic tenor of the works from these fragments. Leonardo’s was clearly more focussed on emotion and movement, and Michelangelo’s entirely on the anatomy of the male form.

So, where does Raphael fit into the designs for Anghiari and Cascina? The final pictures in the exhibition are a handful of drawings by Raphael: one, after Michelangelo’s Bathers; the other, a thumbnail sketch of Leonardo’s horses. These sketches bring us full circle to the first room, where we initially saw Raphael’s responses to the Tondo, David, and Leda. As we exit the space, the show leaves us with a lingering message: that a good artist really does copy a great deal.

Renaissance Florentine art is, without question, a dialogue rather than a monologue — and though you might have a favourite (Giorgio Vasari certainly did…) there’s certainly room at the top for all three.

Catch it at the RA until February 2025.

Fin.

One of the most interesting articles yet, thank you! Seems like a must-see exhibition. Time to look up Vasari’s favourite, which maybe I should have known already..

This is like reading Exhibition on Screen, I love this