In Praise of the Animal Crossing Museum

Video games are high art too, and here's why you shouldn't dismiss them

Image: The Italian Renaissance gallery in the Animal Crossing museum.

Unless you have been living under a rock since 2020, you have probably heard of Nintendo’s Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Conceived in 2001, the premise of Animal Crossing is one of ‘cosy gaming’. It is not supposed to be thrilling or anxiety-inducing: there is no shooting, street fighting, exploding, nor really any narrative to speak of. You play as a rotund little human, running around an island (or, in the earlier games, a village or city), making friends with talking animals. You plant flowers, catch bugs, pull up weeds, decorate your house, trade turnips on the ‘stalk’ market. You can architect your own landscape, and decorate your animal friends’ houses. The whole point is to rejoice in the meditative idyll of your own personal Eden. My island is called ‘Arcadia’.

My favourite aspect of Animal Crossing is the museum. It is run by an owl wearing a bow tie. His name is Blathers (his sister, an astronomer, is named Celeste). There are four sections: including a section on natural history, an aquarium, and an insect house. The piece de resistance, however, is an art gallery that contains 43 of the most important cultural objects in human history: think Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and Michelangelo’s David. You can find the full catalogue here. Just to the left of the art gallery is a delightful museum coffee shop run by a pigeon called Brewster. He serves pigeon milk lattes (..but one wonders where he gets the milk…?).

When you start to play Animal Crossing, however, you cannot explore the museum immediately. It arrives totally empty. Blathers doesn’t have any collections to speak of (I mean, he is an owl)... so it’s your job, as the player, to fill it with objects for you and your friends to enjoy.

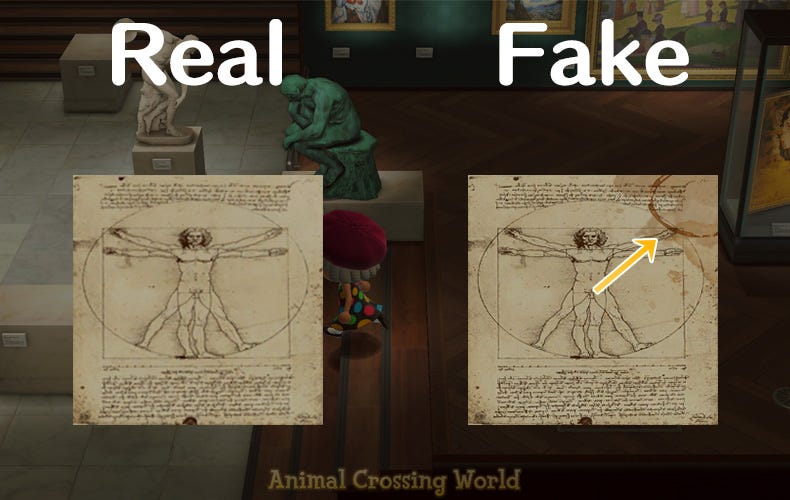

You can find fossils by digging, bugs by netting, and sealife by fly fishing and diving. The artworks, however, you can only obtain very infrequently from a dodgy travelling antiques dealer (a sly fox called Redd). His wares are only genuine twenty five percent of the time: the rest are all fakes. Spotting these fakes is actually really difficult. Even while studying my PhD in History of Art, I find myself shamefully turning to Google when the antiques trawler lands on my island.

For instance, Animal Crossing’s fake Mona Lisa can only be identified by its suspect eyebrows. The faux version of Girl with the Pearl Earring is exactly the same as Vermeer’s original… apart from a slight change to the shape of her jewellery. Redd’s imitation Discobolus has an imperceptible fault on the right wrist. The wrong Venus de Milo has marginally different hair. It’s tough!

Image: Animal Crossing’s real versus fake ‘Vitruvian Man’. Source.

When you have correctly identified and purchased one of Redd’s originals - say, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus - you can submit it to the museum gallery. Henceforth, you can go admire it whenever you like. To reward your efforts Blathers the museum owl will have written an informative caption about its history, and a short visual analysis.

On Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, for instance, we are told the following:

‘It depicts a young princess with her “ladies-in-waiting.” The artist himself is seen to the left. The king and queen are reflected in the mirror to the artist’s right, so the perspective is that of the king. The king… watching the artist… paint the king and queen.’

Having tried to explain this painting to high-school Art History students… I’m not sure I could have summarised the complex metatheatre of Velázquez’s masterpiece nearly as succinctly.

Let’s look at another caption by Blathers, this time for Rembrandt’s The Night Watch: ‘This masterpiece, painted by 17th century Dutch artist Rembrandt, depicts a military gathering. At the time, portraits usually showed their subjects standing still. So this was a leap forward in technique. For many years, art scholars thought the painting was set at night, but a restoration revealed a dark varnish. We can now see the dynamic and poses and lighting as they were meant to be seen - in the daytime!’

Blathers has touched on some important context here: like the shift we see in sixteenth and seventeenth-century painting from static portraiture to dynamic composition. He also draws our attention to Rembrandt’s distinctive technique of ‘chiaroscuro’ - the use of contrasting light and dark tones to create volume and drama.

Another great caption comes in Blather’s analysis of Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners: ‘The signature piece from Millet, who was known for depicting the lives of commoners in the 19th century. Notice the abundant crops visible in the background relative to the meagre wheat remaining for workers.This art served as social commentary in a time of great inequality”. Unironically, I have read significantly worse (and much longer) analyses of French genre painting in academic essays. If you believe video games are bad for the mind, think again. Get your child a Nintendo Switch immediately!

So comprehensive and iconic is the Animal Crossing museum that it has acquired a real-life cult status. For example, in 2023 the gaming influencer Mayuren Naidoo (@mayplaystv on Tiktok) travelled across the world to see each work in Blather’s catalogue. The project was called ‘animal crossing art irl’, and you can watch it here.

Another instance of real-life application of fine art in video games happened in 2019, when Notre-Dame tragically burnt down. Ubisoft, the developers of a game called Assassin’s Creed Unity which was set in eighteenth-century Paris, had digitally mapped the entire building, and provided this blueprint towards the rebuilding efforts!

I have seen academics readily argue for the status of tweets as poetry, for fanfiction as literature, and football as religion, but I have rarely seen anyone defend video games for what they are: an infinitely expansive form of art, with the potential to utilise almost every imaginable creative medium.

More than this, however: video games also give unprecedented agency to the player/reader/viewer. You can’t literally enter into a painting: that is, you can’t until you play a game like Super Mario 64 or Banjo-Kazooie where exploring paintings is literally the entire premise of the game. The same process happens in Luigi’s Mansion and numerous times across the The Legend of Zelda franchise. And what about games like Okami or Epic Mickey where the gameplay mechanic relies on the welding of a paintbrush?

Image: Boss battle in ‘The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time’ where your enemy (Ganon) jumps out of a painting. Source.

I think - and I really do think this - if you consider yourself a consumer of culture, and you’ve never picked up a gaming console, you are really missing out. If, like my father, you think you’re too old, this is not true! Look at this 87-year-old grandmother, Audrey, who clocked in a whopping 3,500 hours on her impressively decorated Animal Crossing village:

So fabulous was Audrey’s creation that Nintendo allegedly created a new character for her in the subsequent game: a sexy fox called Audie (no, I’m not joking).

If you need further convincing, I urge you to read Gabrielle Zelvin’s Tomorrow Tomorrow Tomorrow, the winner of Goodreads Best Fiction (2022). This book, which focuses on the relationship between two young game developers, situates video games alongside high art and literature (hence the Shakespearean title). Zelvin is part of a new generation of artists and writers who grew up on video games, and whose work is beginning to reflect that inheritance in a positive way.

Nintendo will release a new console in 2025. I hope that the new instalment of the game comes with an even bigger museum catalogue, so I can finally put The Creation of Adam in my house.

Image: Me, showing off my completed gallery (no mean feat) - how many of these artworks can you name?

Fin.

I absolutely loved this! Love Animal Crossing & video games on the whole - in grad school I wrote an essay arguing that video games (I chose "Breath of the Wild" as a case study) offer the most perfect experience of Tolkienian enchantment because they are entirely immersive in a way that a film or book can't exactly be. I wish they would get more attention as art forms and cultural artifacts.