Let there be Light

What exactly was 'The Enlightenment'?

It is a cloudy, moody evening, and a family has gathered in the drawing-room to witness a science experiment. Through that experiment, they seek to understand the natural, and ultimately divine, laws that govern the world.

On the table sits a contraption of wood, brass, and glass. Inside it is a white cockatoo. Only very recently, that bird was sitting in its cage. Now, it is being starved of air.

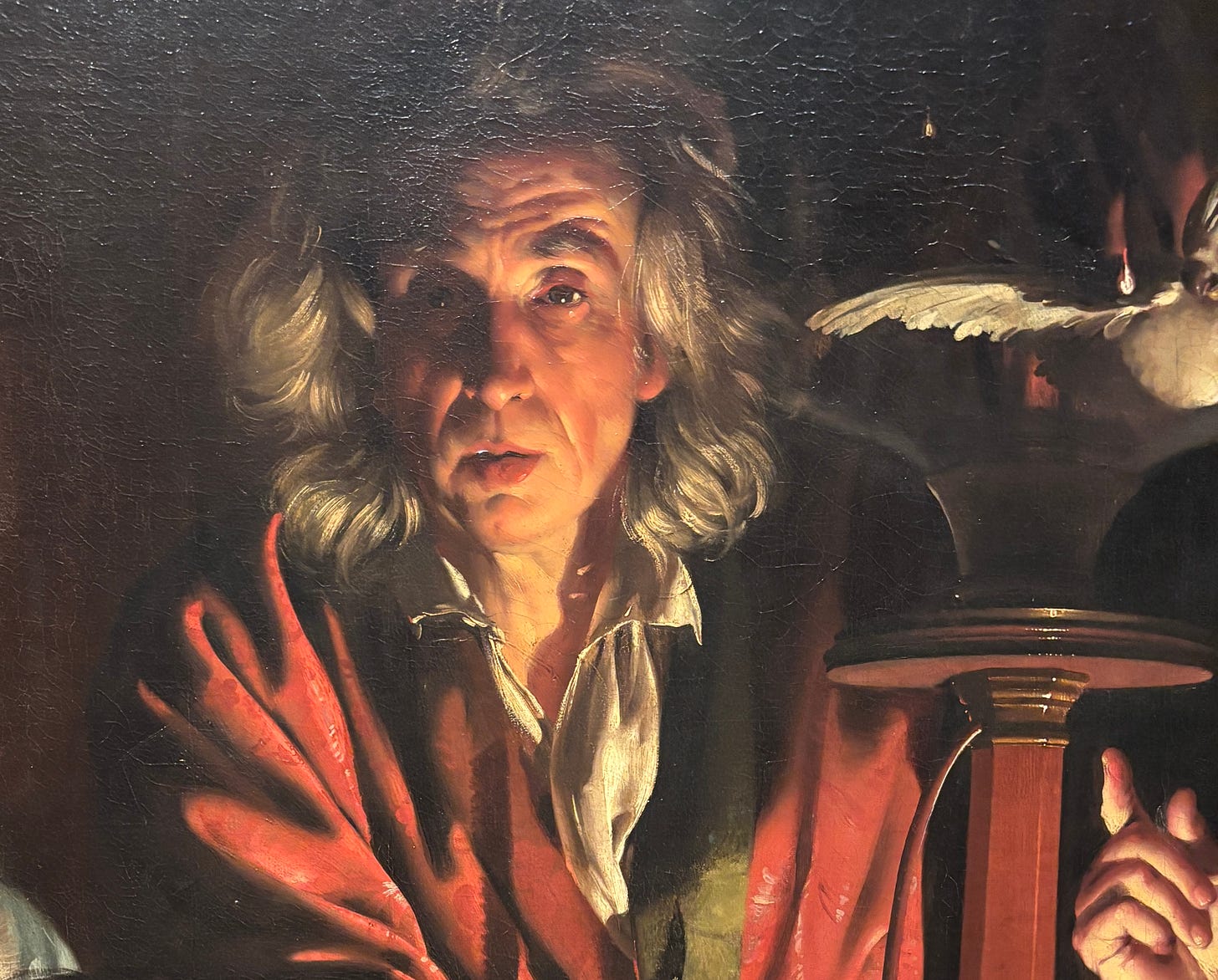

The man who possesses the power to free the bird hovers over the machine. He is a travelling lecturer: an educated man, employed by the patriarch to his left, to instruct the family in the ways of ‘natural philosophy’. He gazes out of the painting, directly at us: implying that we, too, are complicit in the experiment.

This tableau, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), is one of the defining pictures of eighteenth-century British art. It is part of the permanent collection at the National Gallery in London. Until May 2026, you can see it as part of a spotlight exhibition, called Joseph Wright of Derby: From the Shadows.

Like many of Wright’s pictures, The Air Pump is defined by a singular light source. This takes the form of a candle, hidden behind a bowl (which contains a memento mori, a human skull) in the middle of the desk. The candle flame illuminates the faces of the watchers: three intrepid men, three terrified children, one pedagogic father, and a pair of indifferent lovers. That candlelight is the narrator which tells us where to look, and it also symbolises the illuminating power of knowledge.

Joseph Wright, like many of his contemporaries trained in the Academic tradition, was proficient in painting portraits and landscapes. However, he is best known for nocturnal, candlelit paintings. He developed this style as a way to differentiate himself from his peers. It’s true: when you think of eighteenth-century English painters, like Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Stubbs, their subjects are lighter, more conventional, and less sublime.

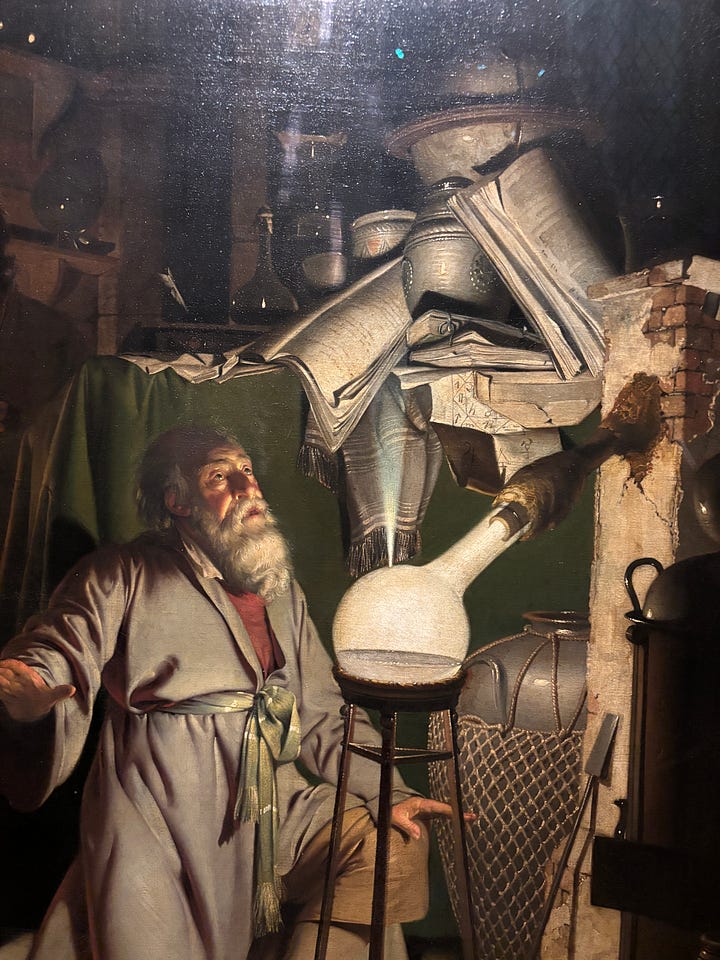

Wright, in his attention to darkness and realism, is consciously emulating the works of seventeenth-century Baroque painters: Caravaggio and the Dutch masters. He adapted their painterly style of deep, dark shadows and bright, striking highlights. The technique is known as chiaroscuro (meaning ‘light-dark’) or tenebrism (from tenebroso, meaning ‘darkened’).

Wright was the first major British painter to apply that dramatic, Baroque style to the industrial revolution. Rather than depicting events from the Bible (like the Italians), or tavern scenes and vanitas (like the Dutch), Wright wanted to depict the Age of Enlightenment. Blacksmiths, forges, furnaces, mills, scientists, philosophers, and alchemists: these are the characters who populate Wright’s paintings.

The deep, dark chiaroscuro which Wright uses to illuminate these subjects imparts an almost religious reverence to them.

This is why the lecturer in The Air Pump feels so powerful. The bright highlights on his face, his glistening white hair, piercing eyes, definitive gesture — all of these suggest divinity. He is playing God.

Wright’s insights into the world of the Enlightenment were closely based on his social context. He grew up in Derby, near the site of England’s first manufactory.

Later, he became closely associated with the Lunar Society of Birmingham. This was an informal network of inventors and intellectuals who met regularly to talk about developments in industry and science. Key figures included Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles), Matthew Boulton, James Watt, and Josiah Wedgwood (yes, of the ceramics).

All were powerful, influential men who lay at the intersection between science and industry. You can see how they inspired Wright’s artwork.

But what was The Enlightenment?

In simple terms, this was was a period in European intellectual culture, between the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, which prioritised reason, logic, and the scientific method.

The Enlightenment was not irreligious. On the contrary: Enlightenment thought was governed by the principle that scientific order was evidence of God’s intelligent design.

So, when you think of the Enlightenment, think of harmony, balance, and inquiry. Think of mathematics, Bach, and philosophy. And wigs.

In any case, during the Enlightenment, knowledge of all kinds was becoming increasingly accessible to larger audiences. Print and theatrical culture was thriving, as were travel and tourism, mechanisation, trade… this was the period which saw the emergence of what we call the public sphere.

This public culture of intellectual curiosity is what Wright is often addressing in his work. We see this particularly in his ‘experiment’ paintings, like The Air Pump and The Orrery, where children and women feature among the spectators. A child is also the central figure in the beautiful and mysterious Girl Reading a Letter. This painting is about the illuminating, and potentially corrupting, power of knowledge.

But for all the attention which Wright of Derby pays to the motif of ‘Enlightenment’ or ‘illumination’, he is not uncritical of the scientific method.

In fact, even though Wright is firmly (even, definitionally) an Enlightenment painter, his paintings always retain a sinister, occasionally Gothic, sensibility which push them in the direction of Romanticism.

Many of these paintings include skulls, skeletons, and ominous, glowing moons. A tension between curiosity and cruelty, darkness and lightness. The Air Pump is an affecting example of this. It is both sinister and intriguing in equal measure.

The point with Wright of Derby is this, I suppose: knowledge is worth pursuing, but it also has consequences. To quote my last Substack — ‘only monsters play God’.

This post is proudly produced in affiliation with the National Gallery’s Creator Network 2025/26.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support my work, but can’t commit to a full-time subscription, why not leave a tip?

Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my TikTok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates.

Thank you for this illuminating and informative piece! I remember this painting "The Airpump" – it was on the cover of an edition of the novel "Frankenstein", which I've just reread.

How did you know I asked in my mind if the Wedgewood was the one from the ceramics?