Medieval Art: Where To Start?

8 Gothic reads for your TBR

The Culture Dump sees another wonderful guest post today. Introducing Maia Béar: PhD candidate at Yale University, medieval arts specialist, and all-round brain box. Her are her top reading recommendations for illuminating the so-called ‘dark ages’.

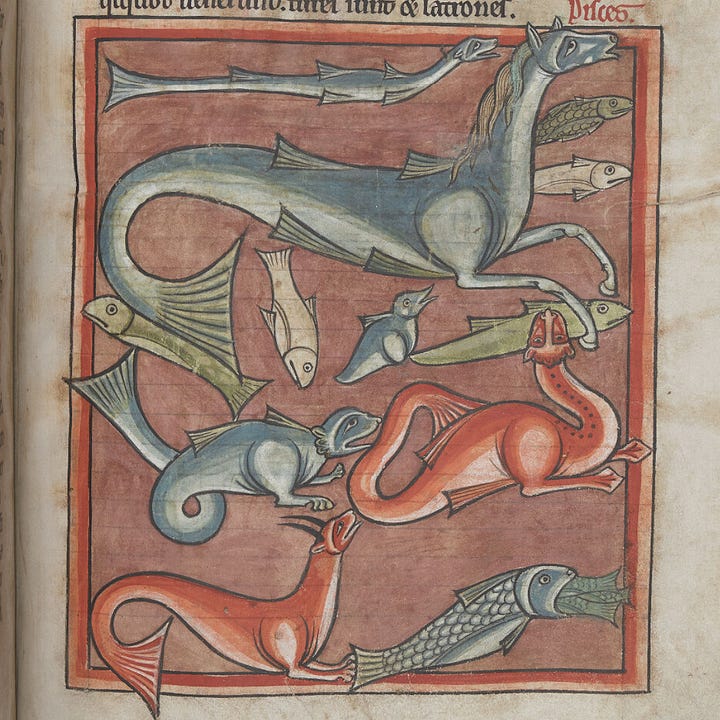

You never know what you’re going to find in medieval art. A map of the world from the year 1300 might show Moses receiving the Ten Commandments or headless men with their faces in their chests. A bestiary, or book of animals, made in England is as likely to contain unicorns and phoenixes as it is horses or sheep.

The viral images of nuns plucking penises from trees are so popular that you can, should you wish, have a sticker of the scene shipped to your home in 2–4 business days. (£1 plus postage – not bad.)

Plumbing the depths of the archive of medieval art to find these strange and entertaining gems, however, can be a daunting task. Centuries of dismissal as the ‘Dark Ages’ have left the medieval era understudied. Fewer popular art-history books are published on medieval subjects than their Classical predecessors or their Renaissance successors, and anonymity was the norm among medieval artists, so you won’t find many biographies of painters, sculptors, weavers, or other craftspeople from this era of history.

The vagaries of history have done the period dirty too. Many of the cathedrals and churches which originally contained a huge number of medieval statues and paintings were devastated in the Reformation from the 16th century onwards, while tapestries and manuscripts have fallen prey to fires and floods. This makes it hard to see medieval art in situ unless you know exactly where to look, and galleries tend to host fewer major exhibitions showcasing medieval art than works from other periods.

That’s where this list comes in. You’ll find a range of options here – a couple of overviews of the period, a couple of studies of specific areas and forms, a wonderful novel, and a brilliant blog.

Disclaimer: this list should really be called ‘Late Medieval Western European Art,’ but that made it harder to put a rhyme in there. I must acknowledge that the list skews heavily towards my personal research interests, and with good reason – as a specialist in English art and literature from the years 1250–1500, my expertise lies in the visual culture of late medieval Western Europe specifically. It would be a disservice to my colleagues who work on early medieval material or material from other regions to attempt if I were to put together a reading list in their fields of expertise. Having said that, I’ve tried to reach beyond England and draw up a list that speaks to the incredible diversity of visual cultures in the medieval world.

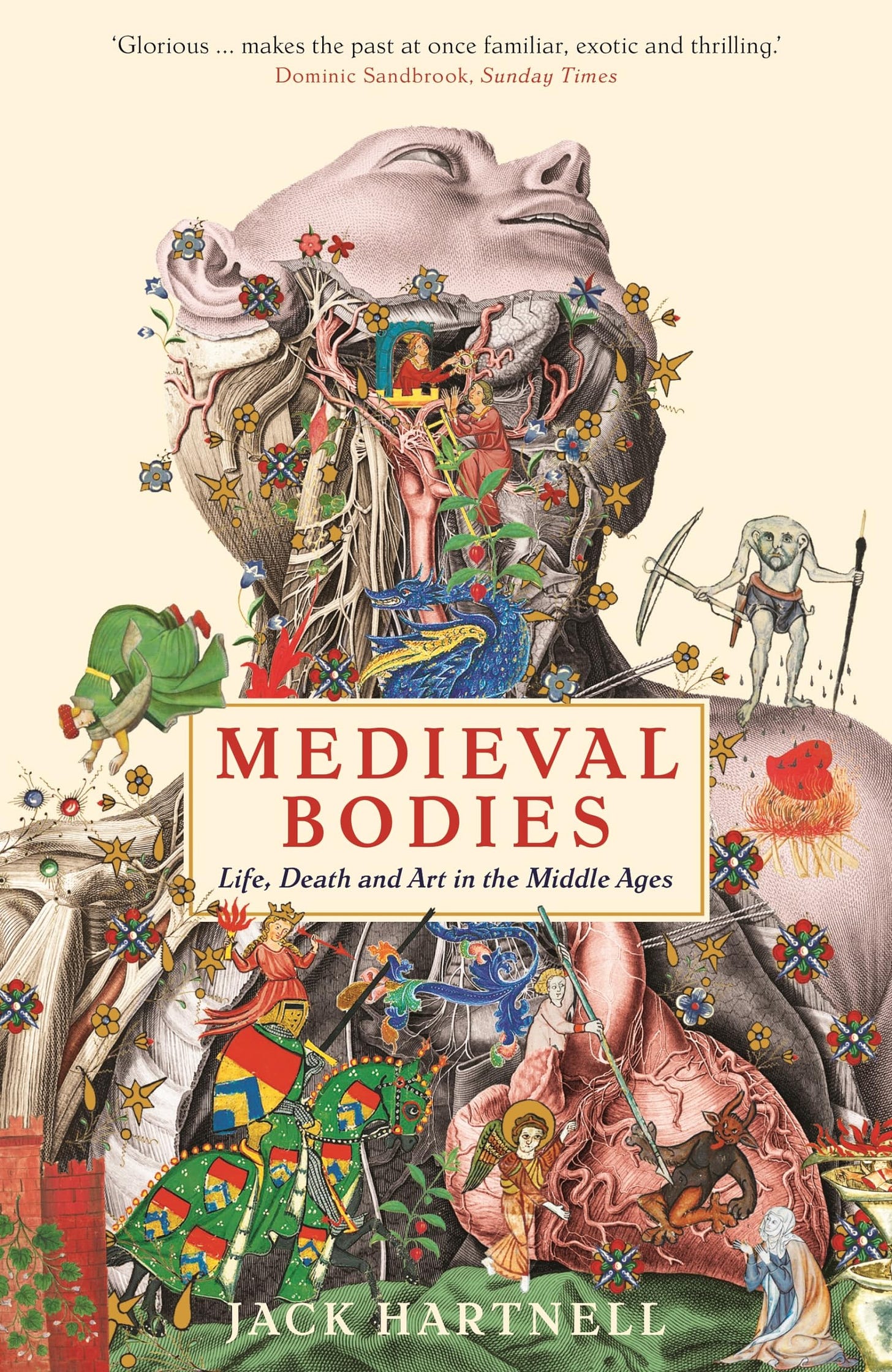

1. Jack Hartnell, Medieval Bodies: Life, Death and Art in the Middle Ages (2018)

This book is an absolute must-read for anyone interested in not just how medieval art depicted the human body but also why bodies appear the way that they do in medieval images. Medieval Bodies combines the histories of art, medicine, philosophy, and religion to present a holistic picture of how medieval people saw their own bodies and those of others. Produced in collaboration with London’s Wellcome Collection, it’s incredibly deeply-researched but highly accessible.

Hartnell’s book is structured according to different body parts, with chapters starting at the head and the senses and ending with the stomach, genitals, and feet. This structure isn’t just a tidy way to organise a book about bodies – it also reflects the common medieval categorisation of body parts according to their perceived moral and spiritual value. Hartnell, embracing the principle of global scholarship, brings a huge variety of sources into the conversation, from German prints to Slovenian wall-paintings and Islamic medical manuscripts to Egyptian clothing. There are plenty of enjoyably grotesque moments – I particularly like Hartnell’s inclusion of French entrail effigies, marble statues of dead kings and queens who hold their internal organs in little bags on the outside – but it’s also a serious work of scholarship. Ultimately, Hartnell holds in tension the proximity to the past which medieval art affords its modern viewers and the alienation produced by the in-depth study of its contexts. It’s hard to imagine a reader who wouldn’t be intrigued, delighted, and provoked to thought by this exceptionally good book.

2. Elly Truitt, Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art (2015)

One reason I love this book so much is that it demonstrates how medieval scholarship can challenge our definitions of art. Automata sound like the stuff of 20th century science fiction, but artists and engineers across the medieval world actually often collaborated to make spectacular mechanical creatures, beings that seemed to move independently and straddled the boundaries between scientific marvels, supernatural apparitions, and manmade artworks. Few survive, but Truitt, a professor in the history of science at the University of Pennsylvania, is probably the world’s leading expert on these objects.

Medieval Robots draws on a vast range of source material: eyewitness accounts of real automata, fantastical visions from fiction and poetry, and beautifully-rendered manuscript illuminations, engravings, and photographs. Truitt pushes the reader to consider questions as profound as where the boundaries between science and art might lie and how different societies have distinguished between living creatures and mechanical artifice. It’s an academic publication, but Medieval Robots is immensely readable and clear; it also has a wonderfully thorough bibliography, which is a great starting point for anyone interested in reading more about moving statues and lifelike robots.

3. Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry, The Bright Ages (2021)

& 4. Janina Ramirez, Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It (2022)

These two books are relatively general histories of the Middle Ages. They share the aim of re-introducing the medieval period as an era of intellectual growth and cultural dynamism as opposed to the barbarous, backward stereotypes often presented in popular culture. The Bright Ages, as the title suggests, combats the trope of the ‘Dark Ages.’ Structured around individuals who changed the societies they lived in – whether through literature, science, the arts, or politics – it combines the well-earned expertise of its authors, both academic historians, with a keen wit and clear, accessible prose.

Janina Ramirez’s Femina also focuses on the lives of extraordinary individuals, in this case the women whose stories have been neglected in male-centric scholarship. We meet scientists, religious mystics, diplomats, and even a female king; as Ramirez puts it in her spiritedly polemical preface, ‘Women have always made up roughly half the global population. Why then should they not inform the way we perceive the past?’

Neither The Bright Ages nor Femina is an art history book specifically, but all medieval history is by nature integrated with the history of art – so much of what we know about the period comes from contemporary sources, like illuminated manuscripts and tapestries, that combined text and images. Both these books draw on the material and visual histories of their subjects for their contents, and both reflect on the use of images in the self-fashioning of individuals and nations. You certainly don’t have to know everything there is to know about medieval history to understand the art of the period, but it can’t hurt – and these two books are great places to start.

5. Russell Hoban, Pilgermann (1983)

Russell Hoban might be better known for his adorable children’s books about Frances the badger, but the American writer was also a prolific literary novelist. 1983’s Pilgermann tells the strange, haunting tale of a medieval Jewish man who narrowly escapes death in a pogrom in a European village and sets off on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He settles in Antioch – a city in modern-day Turkey – in the year 1097, just as the First Crusade reaches the East. Much of the novel focuses on Pilgermann’s design and construction of a mysterious patterned courtyard, which attracts visitors from near and far even as war draws closer. Hoban draws on both Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) and medieval Islamic mosaic and textile designs for visual inspiration, bringing to life the aesthetics of the 11th century in both Europe and the Holy Land.

At times horrifying, at times desperately optimistic, the novel envisions a medieval world in which individual Jews, Christians, and Muslims live uneasily alongside one another as ethnic and political conflicts rage. Hoban, the son of Jewish immigrants from modern-day Ukraine, uses the art of the Middle Ages as a means of reflecting on the modern day, too – the violence that Pilgermann faces on his trek across Europe inescapably calls to mind the horrors of the Holocaust. Pilgermann does not present easy conclusions about how artistic endeavours can unite different kinds of people – the artwork at its centre is enigmatic and elusive, and at times is itself the cause of conflict. Nevertheless, the novel leaves you with a strange sense of hope and possibility, if only in the potential for medieval art to keep inspiring its viewers even in the modern day. It’s one of the most unusual and unforgettable books I’ve ever read.

Content warning: this novel contains graphic depictions of violence, including sexual violence, and is definitely not suitable for young readers or those with a sensitive disposition.

6. Michael Camille, The Medieval Art of Love: Objects and subjects of desire (1998)

It’s no exaggeration to say that Michael Camille completely revolutionised the field of medieval art history. His career was relatively brief – he obtained his PhD in 1985 and passed away from a brain tumour in 2002, at the age of 44 – but his work reshaped medieval studies, introducing critical theory and anthropology and breathing new life into the discipline. Not only was his work revolutionary: Camille was also an openly gay, working class Yorkshireman, who described himself as coming from a home with no books and became a professor at the University of Chicago. Even today, he would be a remarkable success story in the academy; his career was even more remarkable in the 1980s.

This list would be incomplete without Michael Camille, and really any of his works would have been a good pick for it. I’ve chosen The Medieval Art of Love for its wit and undeniable shock factor: Camille exposed the sexuality and lasciviousness of medieval European art, sourcing an incredible range of images that represent not just love but lust. Camille was interested in all sorts of media – manuscript illuminations, marginalia, Gothic stone carving, embroidery, metalwork, and more – making The Medieval Art of Love an excellent starting-point to consider the full richness of medieval visual culture. Camille’s skilful integration of the history of medicine and anatomy also means it would make an excellent follow-up to Jack Hartnell’s Medieval Bodies. I’d recommend getting this one from a library – it’s very expensive online, and although you can find it on the Internet Archive, the pictures look fantastic in real life. This is a serious academic work which rewards close attention, but it’s also a fun and charming read, and a great gateway to the work of one of the all-time greatest scholars of medieval art history.

7. Roland Recht, Believing and Seeing: The Art of Gothic Cathedrals (2008)

Originally published in French, Believing and Seeing is an indispensable compendium of Gothic sacred art. Recht begins by interrogating the meaning of the term ‘Gothic’, arguing that the lavishly ornamented architecture of the late medieval period was not just an aesthetic movement but an intellectual one. He gives an overview of how scholars from the 18th to 20th centuries saw Gothic art and architecture, including some fascinating anecdotes from the French architects who tried to resurrect it as a building style for the modern age. The majority of the book, though, is taken up with an astonishingly thorough overview of the Gothic style across Europe. Recht brings in evidence from French, German, English, Italian, Czech, and Polish cathedrals, ranging from entire cathedrals’ floor plans to specific stained-glass windows and detailed analyses of individual pieces of carving.

Seeing and Believing is a huge read, and one which can be treated either as an encyclopaedic whole or as a source to dip in and out of when visiting different sites. The central case made in the book, put very simply, is that medieval cathedrals were designed according to the belief that sight was the key to religious revelation, which is a compelling argument on its own merits and also means that Seeing and Believing functions as a wonderful guide for actually spending time in Gothic cathedrals. One of Recht’s particular strengths is his ability to tell the international story of medieval cathedrals and the connections between these astonishing buildings across Europe, and this book has another strong bibliography, although much of it is in French or German.

8. Olivia Swarthout, Weird Medieval Guys, and…

This one isn’t just a book! Weird Medieval Guys started out as a Twitter account and became a popular blog, posting about exactly what the name suggests – the strange and hilarious illustrations that can be found in the margins of medieval manuscripts. It’s a treasure trove of bizarre manuscript images, surprising etymologies, and accounts of historical oddities. In 2023 Weird Medieval Guys became a book, which would make a great Christmas or birthday present for your most history-obsessed friend. It’s pretty family-friendly but does contain discussions of death.

Love this post! I have recently become fascinated with medieval art, a brand new art subject for me. I am continually amazed by its weird inventiveness and very glad to learn of interesting books like those listed here. The Bright Ages looks like a really good starting point for me. On my TBR list it goes, and thank you!

I have never seen the nuns picking penises from a tree image. So grateful to you for sharing it hahaha.