On the RA's Summer Exhibition 2024

The summer exhibition in Burlington House is London’s longest-term annual show. Having run without interruption since 1769, it is rather amazing that the exhibition is still so enduringly popular.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that, even at lunchtime on a Wednesday, the RA summer exhibition was well-populated with an energetic crowd. The ambience was loud and colourful, with much shoving, stubbing of toes, and energetic discourse about the next David Hockney and/or Henry Moore. I enjoyed this refreshing dynamism; however, if you’d like a quieter experience I’d recommend going earlier in the day, before the multitudes pile in. Tickets are expensive (£22-24), and the show closes in 10 days (August 18th 2024).

Image: Nos 1086-1345, curated by Anne Desmet, RA.

It is my understanding that these summer exhibitions have always been relatively large and diverse. In the eighteenth century, the primary purpose of these shows was to showcase the broad potential of British artists, who had historically been overshadowed by the great schools of early-modern Italy, Holland, and France.

Now, I get the sense that the summer exhibitions are one of the few avenues of exposure which British artists can hope for. The popularity of the show is certainly encouraging, since it at least proves that the contemporary fine arts are alive and kicking at the RA (the same cannot be said for the old masters: the Flaming June exhibit in the Gallery Collection is replete with tumbleweeds…). But I do think that the conspicuously older crowds, as well as the pricey entrance fee (only £2.00 is deducted for concessions), provide evidence of some innate structural problems which will have to be dealt with at some point…

The question is this: with one-thousand-seven-hundred-and-ten works to look at, just where is one supposed to start? Pictures are piled on top of one another all the way to the ceiling. This is a defining quality of salon curation (dating back to the seventeenth-century Parisian Academie) but it does make it really difficult to see smaller, higher-up works. Try not to miss these smaller pieces, as they can be very rewarding, but also don’t worry about seeing everything. My advice would be to take your time, and focus on one or two mediums. This exhibition has everything from architectural modelling, to mixed media, painting, prints, and textiles, etc. so there is no harm in gravitating towards what you like, letting intuition guide you.

This point puts me in mind of a series of witty reviews of the RA’s summer exhibitions published by the satirist Anthony Pasquin in the 1790s (you can find them on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online).* These pamphlets poke fun at the pomposity and inflated self-importance of English art critics. Written from the perspective of one such archetype, the critical voice tells us that ‘majority’ of works in these annual exhibitions ‘are scarce worth powder and shot’ (I think gunpowder was expensive in the eighteenth century). By this he means that the effort and resources invested in these artists by the Royal Academy, and by extension the King, are not justified by their output or contribution to the arts.

I do my best to not to be like Pasquin’s pretentious critic. Indeed: the beauty of the summer exhibitions is that no work will stand out to different viewers for the same reasons. Where Sir Joshua Reynolds might have baulked at Nichola Turner’s ‘Meddling Fiend’ - the work which currently greets us in the Burlington courtyard, a writhing mass of horsehair and wool which envelops the statue of the RA’s first president - William Blake, who believed that Reynolds was ‘Hired to Depress Art’, might have jumped for joy.

Image: Nichola Turner, ‘The Meddling Fiend’.

For whatever reason, the following works were the few that stood out to me as really special. I’d love to hear what you think:

No. 334, ‘The Art Critic’, Mario Lafirenze.

Hilarious for obvious reasons. A comic pastiche of the genre of classic nineteenth-century exhibition salon paintings (see: my current profile picture).

No. 174, ‘The Second Homeowner’s Nightmare’, David Mach, RA.

I think David Mach’s picture here is poignant, cynical, and chuckle-worthy. The work itself is highly accomplished, and makes good use of the graphic potential of lithograph printing.

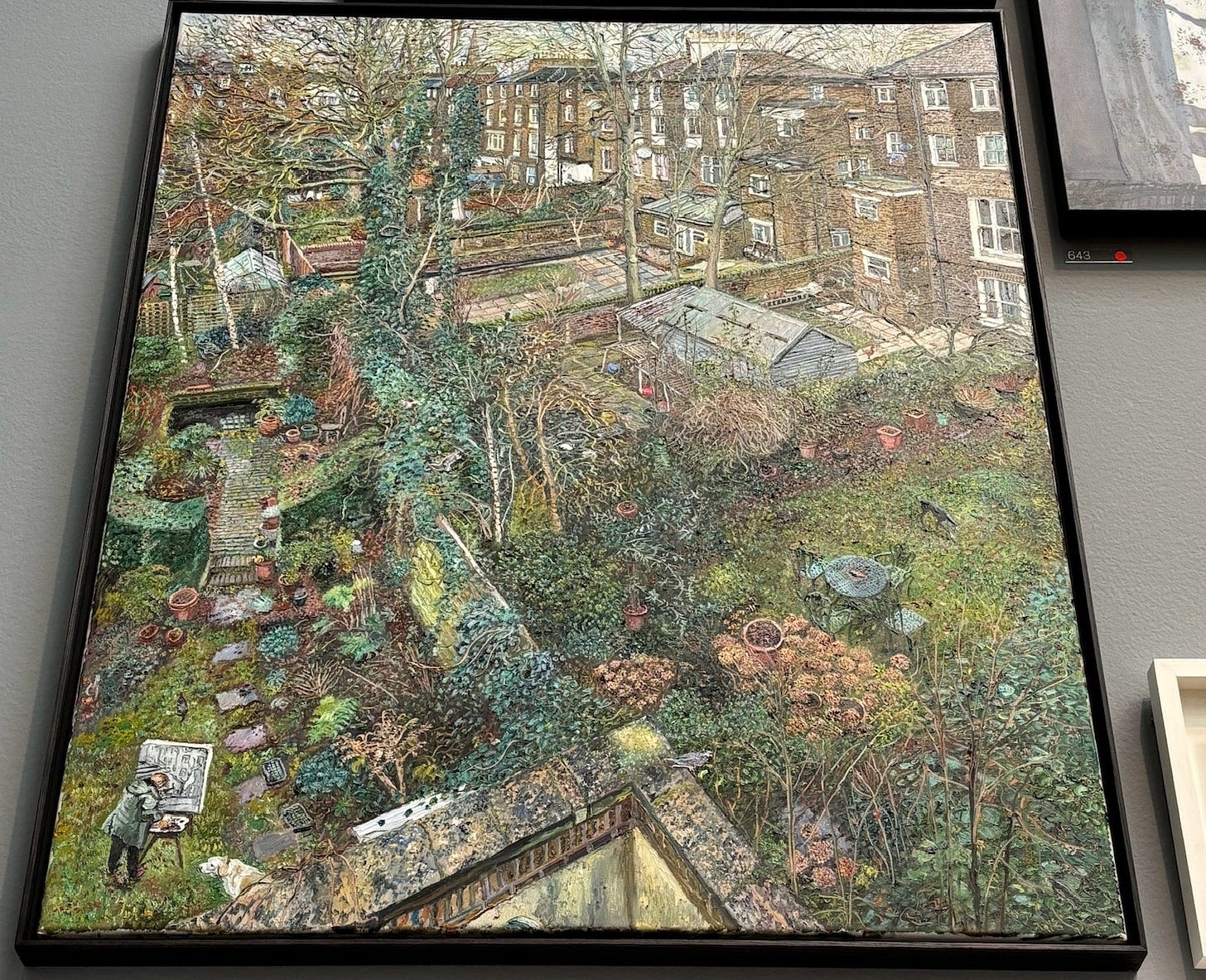

No. 641, ‘Self-Portrait Drawing Space in an Islington Back Garden’, Melissa Scott-Miller.

I love the inclusion of the artist in the bottom left, which gives a self-referential quality. Her Barbour jacket and faithful hound put me in mind of my own mother. The verdant palette and bird’s-eye composition is just so evocative of looking out the window of a terraced house in North London.

No. 950, ‘The Pumpkin Farmer’s Kitchen’, Stephen Davis.

Bring back dioramas! I simply love this little cottagecore scene.

No. 1451, ‘Wayfarer’, Baldvin Ringsted.

An a-symmetric topsy-turvy cross stitch of pastoral European landscapes with unique shape and texture. It is always great to see textiles given a platform in fine-arts spaces, and I particularly love cross-stitch because of its overlap with pixel art (something I imagine we’ll see in summer exhibitions to come).

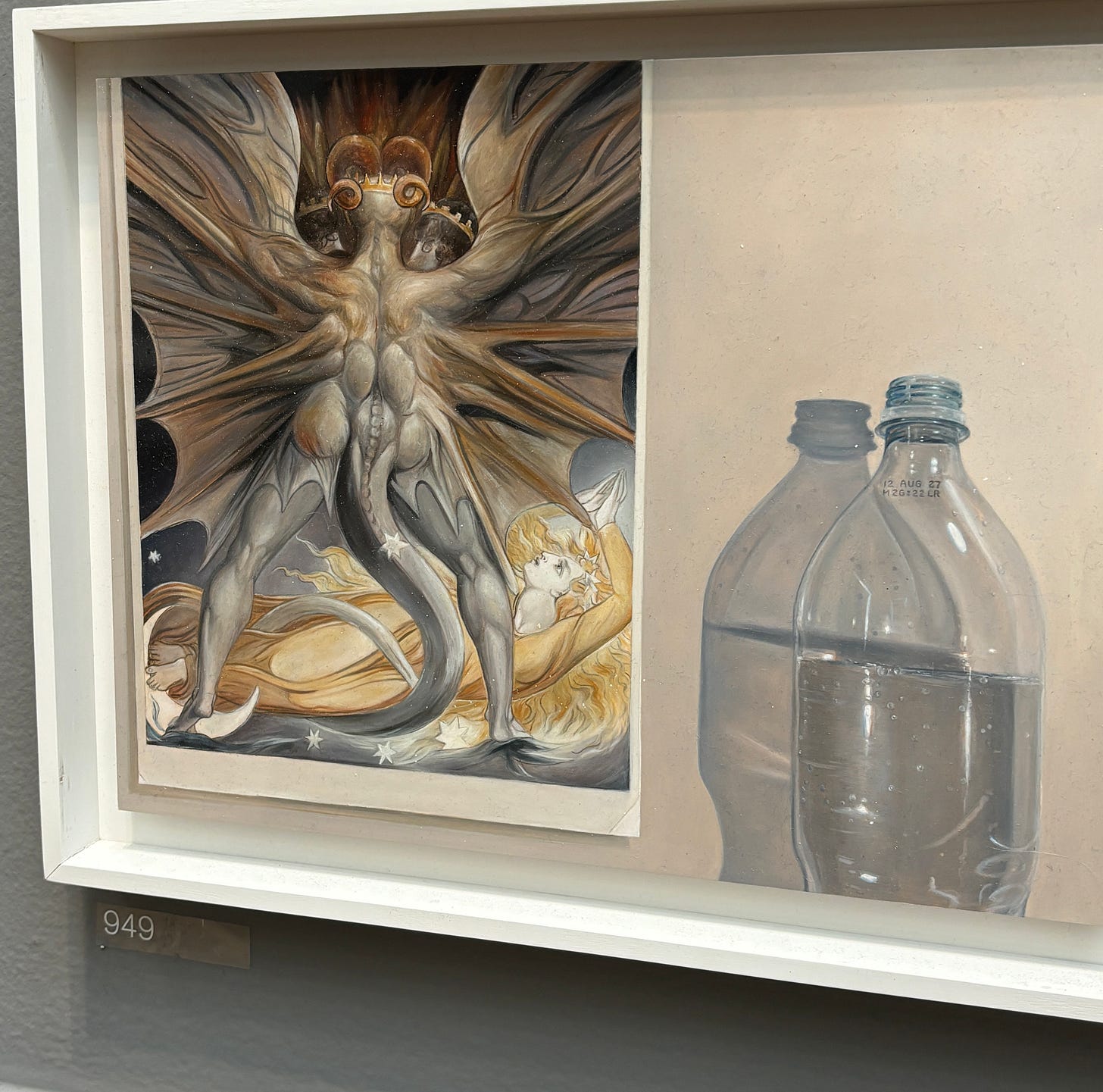

Finally, an honourable mention goes to No. 949: ‘Blake, The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun, With Bottled Water’ by Rachael Robb. Having just written a PhD on William Blake, I was pleased to see his presence in the gallery.

Blake would probably also have been pleased to see his work represented here: not in the least because, during his lifetime, his paintings were ‘regularly refused’ for these exact exhibitions.

Fin.

*Pasquin is a pseudonym which refers to the ‘Pasquino’ talking statue from Rome which symbolised freedom of expression. His real name is John Williams.