In your mind’s eye, picture the city of Paris, circa 1850. You’re standing on the rue Bonaparte, in the historic district of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Directly in front of you is the École des Beaux-Arts, the most eminent art school in Europe.

The building is a labyrinth of courtyards, cloisters, and Classical statues.

It’s early in the morning, but the street is already crowded with students. They jostle past, stinking of turpentine and body odour. They are rushing to their next life-drawing class, or perhaps to the school’s antiques gallery, intent on studying plaster casts of Apollo and Venus. Maybe they’re heading to a local antiquarian bookseller to find reference materials — folios of prints after Rubens and Delacroix, or cheap sheaves of Japanese wrapping paper. The atmosphere is electric, chaotic, and fiercely competitive.

Success for these desperate students would have been determined by one thing and one thing only: exhibition at the venerable Paris Salon. To show one’s paintings at the Salon was to earn one’s place in the annals of French art history: alongside Ingres, Géricault, and Delaroche.

In 1850, there were far more art students in France than there were spaces at the Salon. Works by better-known artists were often chosen over new ones, so it was very difficult to break through.

Anyway, even if a new artist did qualify for the Salon, their painting might be displayed in an uppermost corner of the wall, essentially invisible to the public.

The Salon also had incredibly rigid rules about what kinds of paintings were acceptable for exhibition. They prioritised grand, masculine, dramatic subjects: scenes from Greek myths, or from the Old and New Testaments, or from Shakespeare and Goethe, or from French military history. All of these works were expected to be as detailed and formal as possible, finished in oils, and properly composed.

Portraits were acceptable, though less so than historical pieces. Landscapes were even lesser. ‘Genre paintings’ — paintings of daily life — were considered entirely banal.

Overall, the state of the arts in Paris offered a pretty rotten deal for budding artists. But this all changed in 1863. It all started with Édouard Manet’s painting, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe.

This painting depicted a naked woman (just a normal woman, mind you, not a Venus or Aphrodite) looking out at the viewer. She is sitting in the park having a picnic lunch with two men.

While Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe is not an Impressionist painting, it represents an important precursor to the Impressionist movement. It signifies a provocative break from academic tradition, choosing to focus on daily life, rather than high, mythological subjects. It was painted in a realist style with classical composition, but with a modern, confronting subject. It signified the beginning of a French avant garde, and a breaking free from hierarchies of genre, perspective, and visual narrative.

The picture — along with two thirds of all other paintings submitted in 1863 (including works by Gustave Courbet and Camille Pissarro) — was rejected from the Paris Salon.

Infuriated, Manet exhibited this painting at a rival Salon: the Salon des Refusés. This exhibition had been set up in response to complaints from failed exhibitors and, surprisingly, the Salon des Refusés was unprecedentedly successful.

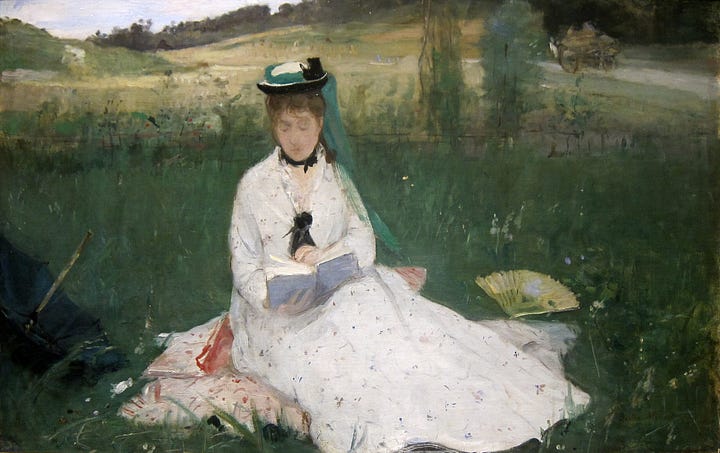

Manet inspired later painters — Impressionists — like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Paul Cézanne. Monet experimented with water and light; Renoir, with softness; Degas, with movement; Morisot, with femininity and interiority; and Cézanne, with geometry and perspective.

So… want to learn more about the Impressionists?

I’ve got some reading recommendations.

1. Sue Roe, The Private Lives Of The Impressionists (2006)

This pithy little book offers a collective biography of the Impressionists: from Manet, to Degas, to Monet, and all the others. It’s densely packed, and well-priced, and it covers all the essential bases, with little room for manoeuvre. There’s not much fiction here.

We’re introduced to the Impressionists in quick succession, and Roe expertly weaves their personal stories with the ups and downs of their artistic lives. It’s a complicated, chronological retelling but it’s also well-researched and even contains some colour illustrations! That’s pretty good for a paperback.

2. Robin Oliviera, I Always Loved You: A Novel (2014)

Centred around two much-romanticised artistic relationships — Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas; Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot — this novel takes a historical-fictive approach.

It’s rich in dialogue and internal monologues. It fills out a tragic love triangle between Morisot, Manet, and Manet’s brother, Eugène, whom Morisot married in 1874. It gives colour to Cassatt and Degas’ first meeting at the Paris Salon in that same year. It uses the social web of these four painters to construct a convincing (if semi-fictional) picture of the Belle Époque.

Fun, fervent, and flamingly passionate.

3. T. J. Clark, If These Apples Should Fall (2022)

T. J. Clark is one of the most poetic art historians writing today. His 2008 essay The Sight of Death is a fabulous, personal, meditation on what it means to experience art: not just as an academic, or historian, or even as an artist, but instead just as an observer.

Clark’s prose is discursive and meandering, beset by a deep, expansive knowledge of his subject. This book, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, offers a careful analysis of Cézanne’s paintings. The writing, like the painter, is uncanny, brilliant, and slightly restless.

Themes include: artistic influence, reality and representation, and perspective. It’s dialogic, sensitive, and beautifully illustrated. What a lovely book.

4. Sebastian Smee, Paris in Ruins (2024)

Sebastian Smee is a historian. He specialises in the Impressionists and the Modernists. He is more interested in context and interpersonal relationships than he is in the formal qualities of visual art… which is no bad thing, particularly if you prefer storytelling over critical analysis.

Smee writes fluidly, narratively, and his most recent publication, Paris in Ruins, is tight and focused. The thesis is this: that the siege of Paris, which took place in 1870-71 during the Franco-Prussian war, profoundly influenced the early impressionist artists.

During the siege, Manet, Degas, and Morisot stayed in Paris. Renoir joined the army. Monet and Pissarro left for England. Smee notes that the distinct absence of war-imagery from the works of these painters in these years make its presence all the more potent. An interesting argument, to be sure. One for the historians to mull over.

5. Eva Figes, Light (1983)

I can’t stop mentioning this book. I’ve recommended it in three of these reading lists now. But of course it had to go here.

Light is a fictional biography of Claude Monet. It’s an ekphrasis of sorts… something like a poem about a painting. The writing is modernist and fluid and slippery. Like some other Modernist books (Ulysses, Mrs Dalloway, A Single Man) Light takes place over the course of one day.

The setting is Monet’s garden. We are in Giverny, France, in 1900. The light is streaming through the trees, and refracting in the water. Monet puts down his paintbrush.

The painting is finished.

Read, read, read!

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my TikTok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Now I have more books in the list of titles to search for! Thank you for this post - and you shared some wonderful paintings too!

I had a physics teacher who rambled on about focusing our "minds eye" now I get it. He read books, lots of them.