So, we’re heralding the end of 2024. It’s been a tumultuous year overall — and the arts are struggling, just a bit.

We’ve seen an overall decline in sales at auction houses. Notably, Sotheby’s and Christie’s experienced a 27% decrease in turnover in the first half of 2024. Moreover, in the UK, the nature of government funding for museums has changed. The recent budget makes it more difficult for some regional institutions to cover their costs. One example is that the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (an amazing collection, by the way) will now have to scale back from two annual exhibitions to just one in the coming years.

However, despite these challenges, there have also been many excellent moments in visual culture over the past 12 months — books, exhibitions, discoveries, lectures, events...

So, before we hurry into the next chapter, let’s take a moment to reflect on the best (and worst) that 2024 had to offer!

Best Art History Books

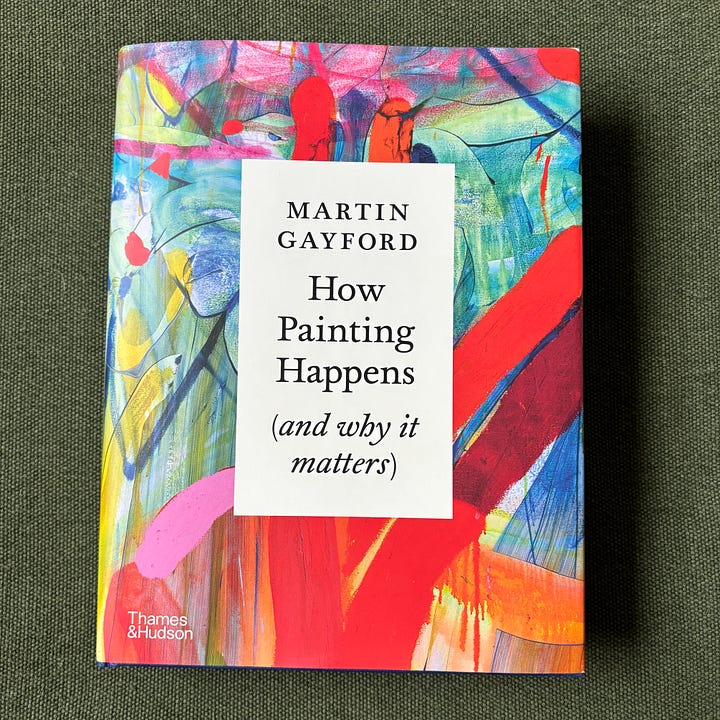

Martin Gayford, How Painting Happens (and why it matters)

This is my favourite art book of 2024, for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, How Painting Happens is a beautiful object. This anthology is hardback and weighty. It’s long and richly illustrated. Although it would look great on a coffee table, it is not a coffee-table book. It’s tightly structured, rigorously researched, and thought-provoking (…it would be difficult to fit in a carry-on, though).

The author, Martin Gayford, is a well-known art critic. He’s written about the modern British school — Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and David Hockney — as well as earlier masters like Van Gogh, Constable, and Michelangelo. Gayford therefore has an expansive knowledge across different eras, which is precisely where this book thrives.

Split into six parts (process, medium, colour, travel, photography, meaning), How Painting Happens jumps from the conceptual realm of art theory to the practical world of technical analysis. What I most enjoyed about the book is how resists chronological storytelling, drawing connections between unlikely bedfellows. For instance: on one page, we see an Edgar Degas (1886); on the next, a figure by Claudette Johnson (2018); and on the next, a Michelangelo (1542). These artists are separated by five centuries, but Gayford links them eloquently.

So, how does painting happen? …with great difficulty, I think.

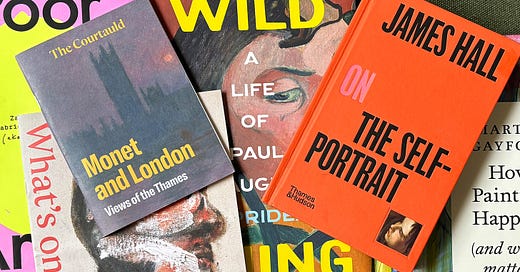

Sue Prideaux, Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin

You have to remember […] I have two natures, the savage and the sensitive. I am putting the sensitive on hold, to enable the savage to advance, unimpeded.

This is what the artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) said to his young wife, Mette, when he was leaving her (with small children, and no financial support) to pursue his artistic career in Paris. He did promise that he would return, but he never did, and in fact ended up moving to Tahiti.

While in Tahiti, Gaugin famously fostered several exploitative relationships with underage Polynesian girls, some as young as 13. It is difficult to reconcile this fact with his artistic legacy. His paintings are vibrant, influential, and full of emotional intensity — but they are also inextricably tied to his behaviour. While Gauguin remains a significant figure in the Post-Impressionist movement, understanding the circumstances of his life make it difficult to view his works without simultaneously grappling with their ethical and cultural implications.

So… how do we reconcile Gaugin’s historic importance with his personal character? Can we truly separate an artist’s creative output from their actions, particularly when their work draws heavily from and distorts the subject (in Gaugin’s case, Tahitian / French Polynesian culture)?

These questions are left up to the reader to intuit and judge in Prideaux’s biography. For this reason, I would say that this book is deeply historical: it tends to focus purely on the facts, refusing to pass judgement on its subject, at least not openly.

Nor do I think these judgements particularly need to be articulated when it comes to Gaugin. He abandoned his family, eloped, engaged in intimate relationships with children, and, in his painting, reframed Polynesian from his own Western lens.

I was pleased to see the publication of this biography this year, particularly because it also seems to have been the year of Van Gogh (first with an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, then at the National Gallery). Gaugin was not really featured in either of these exhibitions, although he lived with Van Gogh for a time in Arles, and influenced his work. Having read Prideaux’s book, I can now see why the curators made this choice. Gaugin is simply too difficult to exhibit alongside another artist, without also opening the can of worms that is Gaugin’s personal life. This needs a lot of careful consideration, and lengthy footnotes.

…but also, without Gaugin, we might not have had Picasso or Matisse, the Symbolists or the Expressionists… so it is useful to understand the development of his art in the context of his life, however uncomfortable this may make us.

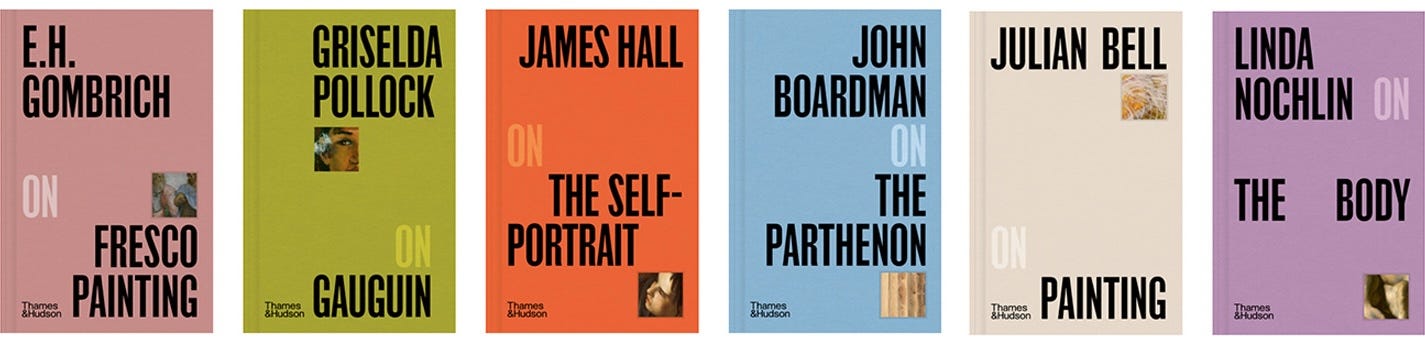

Thames & Hudson, Pocket Perspectives

Now for some lighter stuff. There is a new series of bite-size art history books by Thames & Hudson. They are comparable to Penguin’s Little Black Classics — they’re cute, stackable, and provide just enough cultural info without being overly-long. They also cover an unusually varied range of themes, and have lots of illustrations to boot.

I think that the main draw of these Pocket Perspectives is the diversity and contemporaneity of their authors. Each book consists of a series of excerpts from writings and lectures by teachers, archaeologists, and architects. With the exception of E.H. Gombrich (1909-2001), all of these authors are all still practising. So, reading these books is a bit like attending a seminar from the comfort of your own home.

Right now, the titles on offer are Gombrich’s On Fresco Painting, Griselda Pollock’s On Gauguin, James Hall’s On the Self-Portrait, John Boardman’s On the Parthenon, Julian Bell’s On Painting, and Linda Nochlin’s On the Body. Several more are in the works.

Excellent stocking fillers.

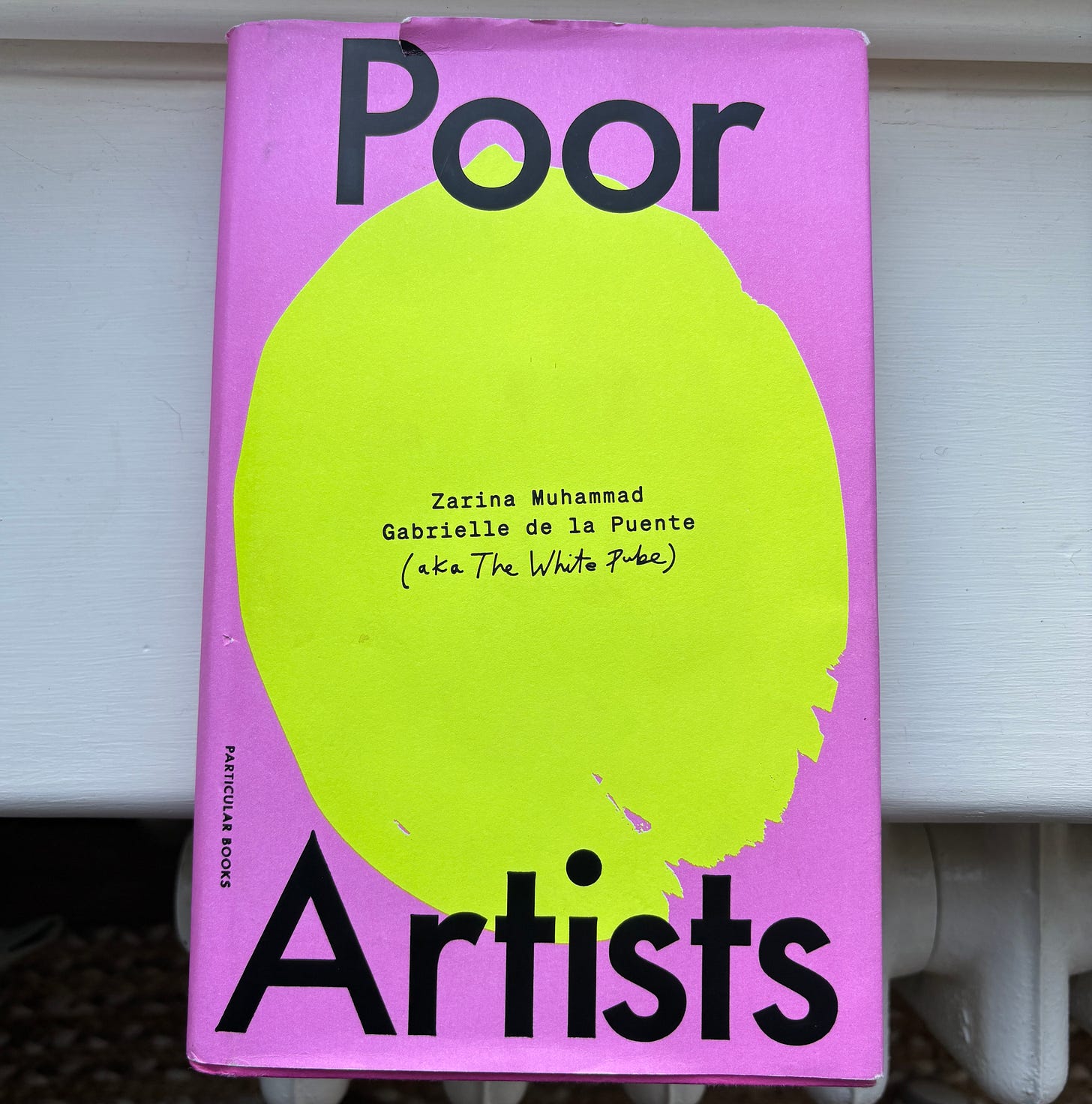

The White Pube, Poor Artists

Yes, this book is written by an author named ‘The White Pube’. This is a satirical take on the name of the ‘White Cube’ gallery, and it’s the pen name of the two co-authors, Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad.

A fresh, authentic take on what it’s like to be an artist in a landscape beset by inequality and limited opportunities, Poor Artists is about commodification, art-making, and art-destroying. It’s also about the experience of growing up. This book is part fiction, part poetry, part Gen-Z slang, and is full of cynical jokes and radical honesty.

It’s not for everyone… nor is it meant to be. It’s supposed to be outrageous, degenerate and infuriating. I think this is why the central motif of the book is a lemon — it’s acidic, sour, and provokes strong reactions.

Overall, Poor Artists is unabashed, experimental, and rather cool. I’d recommend it to everyone, but especially younger people considering going becoming an artist: not just to provide a dose of harsh reality, but also to show them that there are careers in the arts to be made outside of being a painter. The White Pube themselves are examples of this.

My Favourite Exhibitions

In advance of writing this list, I asked my followers to share their favourite exhibitions of 2024. Amazingly, no two answers were the same. We got Sargent and Fashion at the Tate, Frank Auerbach at the Courtauld, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers at the National Gallery, Ranjit Singh at the Wallace Collection, and mentions of exhibitions in Italy, the USA, and Portugal.

This just goes to show how many fabulous offerings there were in the exhibition circuit this year, and just how diverse The Culture Dump’s readers’ tastes are.

Monet and London at the Courtauld

Have you ever considered just how beautiful London really is? Monet was enamoured with it. And what he loved most was the horrendous weather.

This was my top UK exhibition of the year. It was slick, carefully curated, and meticulously organised, with a close focus on a very specific series of paintings. It clearly took years to bring these objects all together in the same room. The pictures are subtle and luminous. It’s a testament to the beauty of my native city (and its fog, rain, and general atmosphere).

Hockney and Piero at the National Gallery

The average person spends about 15 to 30 seconds looking at a picture in an exhibition. This exhibition had only three pictures, so it forced you to spend much longer looking: and looking much more carefully.

So, yes, perhaps Hockney and Piero is a surprising choice for a yearly favourite (especially considering the contemporaneous Van Gogh exhibition in the same venue), but it achieved something very few exhibitions do. It fitted together like a beautiful puzzle and asked the viewer to stand there — at least for longer than 30 seconds — to figure it out.

Thought-provoking. Engaged with ideas about art, inheritance, and influence from Renaissance to the modern day. And all this in only three pictures! Bravo.

Francis Bacon at the National Portrait Gallery

Like pretty much everyone I’ve spoken to about this exhibition, I don’t usually consider myself a fan of Francis Bacon. However, this show made me reconsider this instinctive response. It recontextualizes Bacon as a classic, yet innovative, portraitist. Seeing his works up close made me realise that Bacon is, in fact, something of a modern Old Master.

William Blake at La Venaria Reale

Sublime. Life changing. This might be the best exhibition I’ve ever seen, and it was well worth the commute from London to Turin. Not only did this reignite my passion for Blake’s mystical power, but it also showed me just how exciting it is to exhibit artworks in unusual settings in unusual ways.

The animated figures at the end of the exhibition filled me with hope for a future feature-length Blake-themed epic — a Miltonic journey from Eden to Hell and back again. Who’s ready to animate it?

Notable Happenings

Firstly, in March there was a bit of a boo-boo on the British Museum’s social media. They came under fire for posting about the viral Roman Empire meme, stating the following:

Girlies, if you’re single and looking for a man, this is your sign to go to the British Museum’s new exhibition, Life in the Roman Army, and walk around looking confused. You’re welcome x.

Responses were negative. People felt that the comment was in poor taste, implying, among other things, that women weren’t capable of being independently interested in the Roman Empire.

Then, in July, a Tudor portrait from 1590 was discovered in the background of a photo on X. This long-lost picture of King Henry VIII was spotted by Adam Busiakiewicz, an art historian, who noticed it in the background of a photo posted by the Warwickshire Lieutenancy.

Thereafter, we saw a new attribution to Botticelli’s studio. Forensic analysis confirmed that a tempera painting in Saint Félix Church, at Champigny-en-Beauce in France (initially thought to be a 19th-century copy) dates to around 1510, when Botticelli was active.

On 17 August, a fire broke out at Somerset House, where the Courtauld Gallery houses its priceless collection of artworks, on the Strand in London. Thankfully, the fire was spotted early and extinguished. While the roof was damaged, the artworks were protected… narrowly avoiding a complete disaster.

In September an ‘absolutely hideous’ statue of the Victorian playwright Oscar Wilde was erected near his former home in Chelsea. It’s by the sculptor Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), who also made the statue of Blake’s Newton outside of the British Library (another statue which I take issue with, given that Blake intended for Newton to be a symbol of intellectual oppression).

Then, in November, soup was thrown on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (again). The climate protesters keep throwing soup on Van Gogh, and because of this now we can no longer bring liquids into the National Gallery.

Tragically, in November, the painter Frank Auerbach passed away. A prominent figure in the contemporary British school, his raw, expressive portraits stand alongside those of Bacon and Freud. Auerbach fled Nazi Germany as a child, and his parents were murdered in Auschwitz in 1942. Auerbach’s work exemplifies the power of persistence and reinvention. He often scraped away layers of paint at the end of the day, only to reapply them, creating works that are both challenging and, in their depth and weight, profoundly spiritual.

On a happier note, recently, in December, a beautiful portrait of one of Queen Elizabeth I’s ladies-in-waiting, Lady Leighton, has been rediscovered in a private collection. It is by the renowned English Renaissance miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard. It was found by two academics, Emma Rutherford and Elizabeth Goldring, who believe that the object may have been originally intended as a love token for Sir Walter Raleigh.

And that brings us up to date! My timeline is a bit haphazard — and it’s only the stuff which came across my radar — what did I miss? Let me know.

Looking forward: while I am of course concerned about the current state of funding in the art world, I’m pleased to say that we do have some big projects for 2025. Next year promises a number of fantastic exhibitions, like Turner and Constable at the Tate, Caspar David Friedrich at the Met, and Haute Couture at the Louvre.

I’ll be keeping my eye out for new publications, and continuing with my weekly reading lists and reviews. So, if you want to stay in the loop, consider joining the community here.

Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year!

A lovely summary, thank you so much.💕

I have to say I’m a total fan of the “absolutely hideous “ Oscar Wilde sculpture. I prefer it to the Hambling one. In the Chelsea sculpture Wilde looks as though he is sporting an apparatus like a scold’s bridle - a form of punishment meted out to women to censure their speech. Wilde was ultimately hammered for who he was and for breaching the acceptable. I think there should be room for both sculptures.