I sometimes wonder how many people with a liking for art have absolutely no appetite for non-fiction. I bet it’s quite a few. I never started reading non-fiction until I reached higher education, and even now, I find that textbooks and biographies are never quite as much fun as a good novel — are they?

The books mentioned here are not art history books. They are fictional books about artists: or, at least, books about the process of art-making. These texts are reflections on what it means to be an artist, what creation looks like, and how the artist and their art relates to a wider community… and how none of these things are as happy or as fulfilling as one might initially think.

This niche little genre is distinctively melancholic. The protagonists all possess an idealistic desire to create something truly meaningful. That ‘something’ might be political, or religious, or magical. Rarely, however, does that ‘something’ — perhaps it’s an oil painting, or a mural, or a mechanical butterfly — bring the protagonist the catharsis which they think it will. For better or for worse, their transformation happens through the journey of creating, rather than in the completion of that creation.

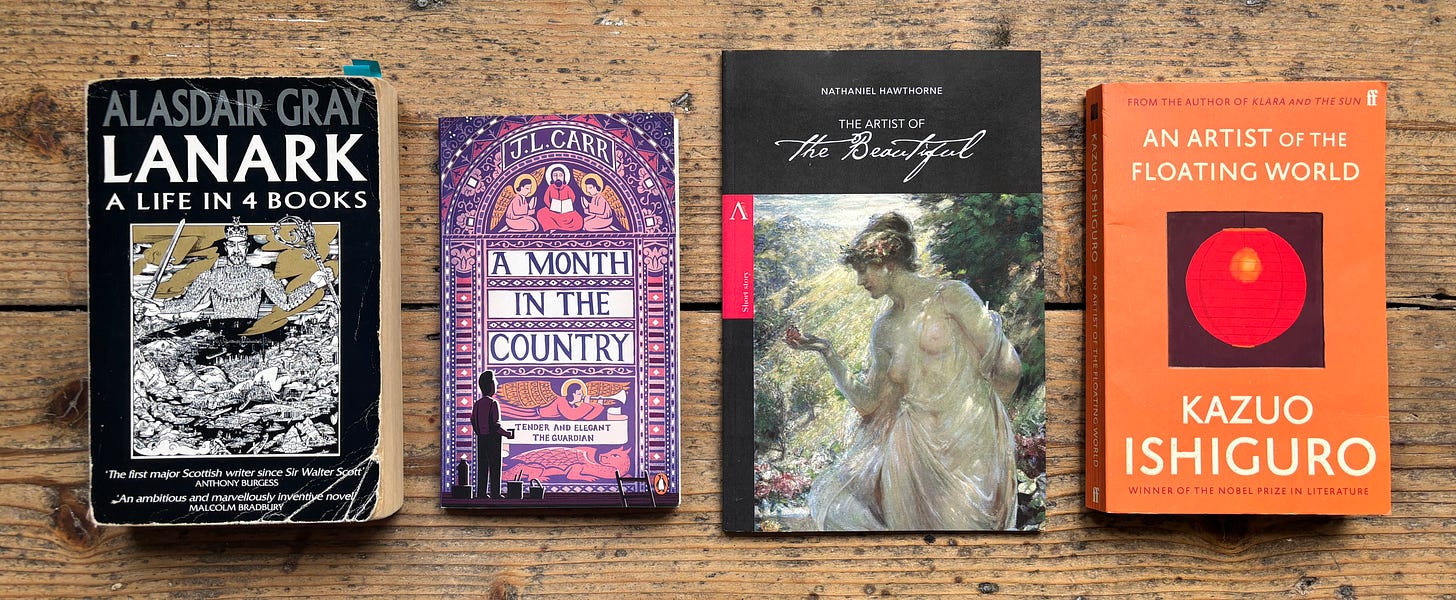

Nathaniel Hawthorne, An Artist of the Beautiful (1844)

Best if you like philosophical short stories

Hawthorne’s Artist of the Beautiful is a twenty-five page meditation on the pursuit of perfection. It asks the question of whether an artist’s lofty idealism comes at the expense of his living a full life, and concludes that a ‘full life’ for an artist is one where creation has been achieved, whatever that cost.

It’s Hawthorne (of The Scarlet Letter fame), so the story is set in a small town in New England in the nineteenth century. The narrative follows an apprentice watchmaker, Owen, who dreams of building a mechanical butterfly so perfect as to be indistinguishable from, or perhaps even better than, a real one.

Owen’s dream is of course misunderstood and mocked by those surrounding him, who see no value in his pursuit of the beautiful, because it provides no obvious utility. His genius is never recognised: and the butterfly, when finally completed, is so fragile that it almost falls apart.

This sad and complex piece of writing implies that Owen’s real achievement does not lie in the completion of the butterfly at all, but in the artist’s lifelong commitment to creating it. His journey captures the tragic gap between idealism and reality, and shows how, sometimes, the impulse to create is the end in itself.

J.L. Carr, A Month in the Country (1980)

Best if you like nostalgic, bittersweet writing

This is a sweet, quietly sad novella about a first-world war veteran, Tom Birkin, who undertakes a medieval mural restoration in a small, disused church in the north of England. It’s set during the British summertime, and it has that slightly heady, dreamy, yearning tone which you might associate with Evelyn Waugh, L.P. Hartley, Ian McEwan, Alan Hollinghurst, and Elizabeth Taylor.

The church mural subject is an interesting one, because there aren’t that many medieval church murals remaining in the UK. Many of them were whitewashed over during the Reformation in the mid-seventeenth century. Those few which have been restored indicate that once our churches would have been covered in truly incredible works of Gothic painting: colourful, imaginative, and spiritually powerful.

The restoration of the mural parallels the restoration of Tom’s own soul. He has been broken and shell-shocked from war. His marriage has fallen apart. He has no money, no prospects, and is in deep emotional torment. Yet, as he revives the painting, he begins to entertain the prospect of building a future.

Tom’s labor is meaningful precisely because it is impermanent. It provides a brief outlet for his personal suffering, and offers him the prospect of redemption. It’s not unimportant that he is painting a Last Judgement: the final reckoning of the soul. This book thus offers a profound reminder that the value of art often lies not in its endurance, but in its ability to console those who seek refuge in creation.

Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981)

Best if you’re looking for an epic

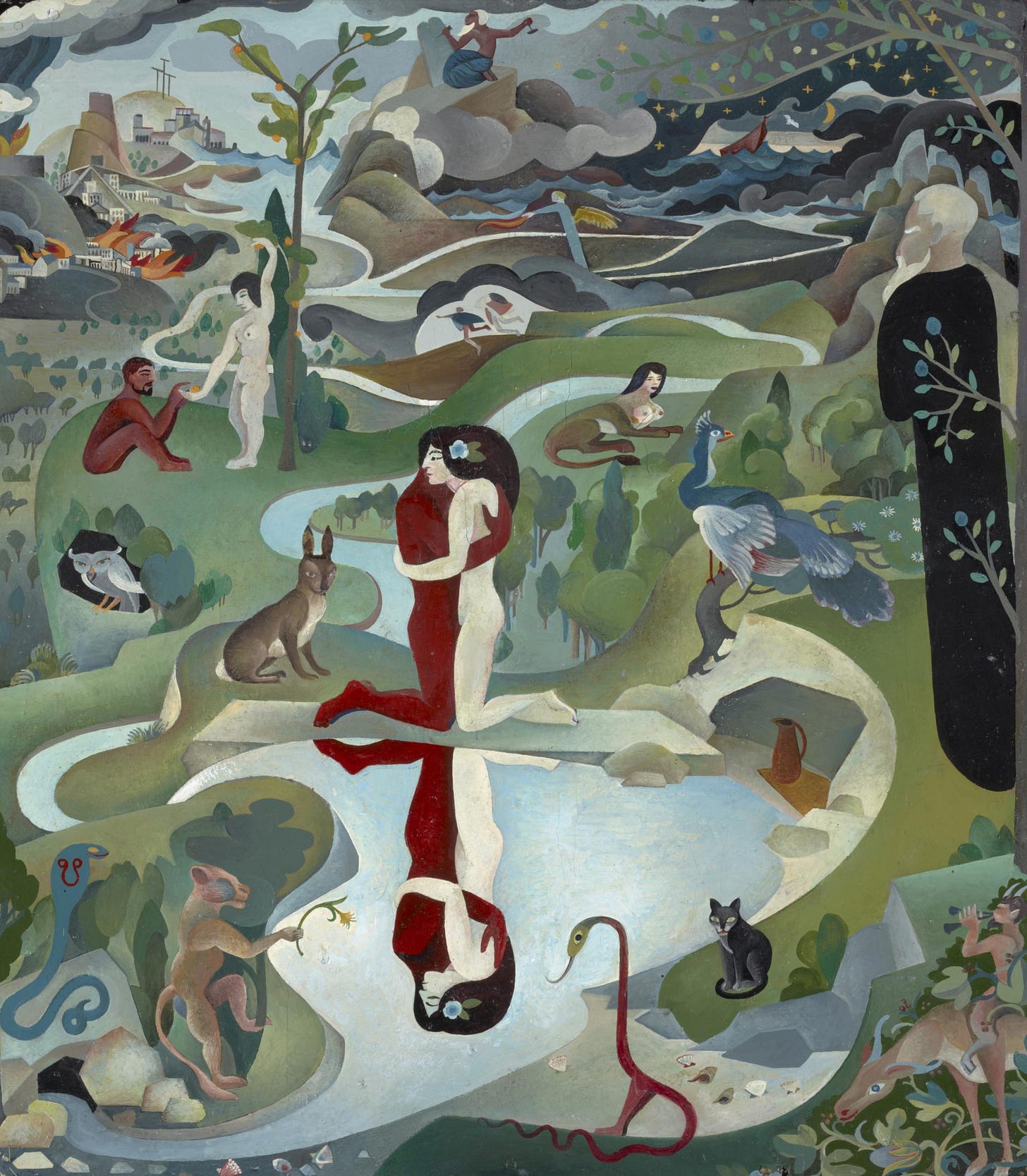

This is my favourite book. It is the masterpiece of the late Scottish artist and writer Alasdair Gray, who also wrote Poor Things, which was excellently adapted by Yorgos Lanthimos into a movie last year.

Lanark is a vast, metatextual novel that defies easy categorisation. It’s structured in four parts, which are all presented to us in the wrong order. It has autobiographical and fantastical elements. It has illustrations (think early-modern engravings, think Dürer, Hobbes’ Leviathan, etc.). It’s full of allusions. It has unconventional footnotes. I’m long overdue for a rereading.

This is a novel about an artist. The protagonist is Duncan Thaw: a failed Glaswegian painter (a metaphor for Gray himself, though also seemingly in part based on William Blake). In the first two parts of the novel (which are, chronologically, the second and third books), we follow Thaw’s early life: his tumultuous childhood, his time at art school, and his final undoing which comes in the form of a mural of the Book of Genesis which he begins to paint in a small Protestant church in rural Scotland.

Thaw’s drive to create something transcendent is both noble and self-destructive. Gray’s depiction of the artist is brutally honest: showing how the desire to resist the expectations of society can ultimately turn into rage, loneliness, and self-erasure.

Kazuo Ishiguro, An Artist of the Floating World (1986)

Best if you enjoy unreliable narrators and difficult topics

This novel is a restrained, melancholy portrait of an aging Japanese artist, Masuji Ono, who is reckoning with his dark, imperialistic past.

Set in Japan after the second world war, the novel follows Masuji Ono, a painter whose work — and we’re not really told all that much about his work — has something to do with imperialist propaganda. Now, in the uncertain years after Japan’s defeat, Ono must grapple with a world that no longer honours what he once created, and reckon with a new generation of Japanese who openly revile his past.

This isn’t a dramatic narrative: it’s a character study. Everything takes place in reportage or memory. Art is sort of at the centre of these memories — whether it’s Ono’s memories of his father burning his childhood drawings, or memories of completing his first propagandist painting — but it’s also interestingly absent. The art of Ono’s past is, as the title suggests, an elusive ‘floating world’.

This title is a reference to ‘Ukiyo-e’. A genre of Japanese art which takes the fleeting, pleasure-filled nightlife life of urban Edo (Tokyo) during the 17th–19th centuries as its subject. In Ishiguro’s hands, though, the term takes on a more sinister meaning, and evokes the dream of Japanese imperialism which Ono’s paintings once represented.

***

The main thing I take away from these books is the idea that the process of art-making is a kind of brutal, inevitable, and unforgiving. It can be as cleansing a exorcism, and as laborious as childbirth. What makes an artist is not the ability to create something which is universally recognised as brilliant. Quite the contrary: an artist is someone who cannot help but create, even if it ultimately leads to their ruin.

If you’ve already read these, some further honourable mentions go to:

Eva Figes, Light (1983) – best if you love the Impressionists and Modernist writers like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce

Émile Zola, The Masterpiece (1886) – best if you’re looking for a slightly more challenging classic read, and aren’t scared of nihilism

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Thank you very much for these suggestions, all of which I now want to read. I have only read A Month in the Country, one of my favourite novels. It is simply exquisite.

Such an interesting list, An Artist of the Floating World was the first Ishiguro I read and I think it's my favourite. A Month in the Country has long been on my TBR list and it sounds like the perfect tonic for my current wistful, nostalgic melancholic state (which tbf is kind of all the time these days 😂)

I've long wanted to read Lanark but I'm hesitant now after attempting Unlikely Stories, Mostly, which I struggled with. Am I likely to enjoy Lanark, I wonder?

One more for your list: The Pornographer of Vienna by Lewis Crofts, about Egon Schiele. I remember enjoying it, though I'm not sure it's considered a classic in the genre.