I’ve got a running theory that Romanticism will be a defining trend of 2025, and I’m not the only one.

For those new here: by ‘Romanticism’ I don’t mean soft, gentle, loving ‘romance’. I mean Romantic with a capital ‘R’. I’m talking about ‘Romanticism’ as a movement in eighteenth-century art and literature: a movement which was all about rebellion, emotion, genius, and, more than any of these, about standing on top of a misty mountain, pondering the meaning of life.

Although I’ve developed this theory from little more than general vibes (so please, take it with a pinch of salt) I do think that there’s a link to be made between the rise of AI and a growing interest in artistic integrity, which is a key tenet of Romanticism.

Romanticism emerged in response to the Industrial Revolution which occurred at the turn of the nineteenth century. In addition to other big societal changes, this era saw the mechanisation of creative industries (such as printmaking, weaving, and metalwork) that had once been the domain of individual artisans or small workshops. With mass production in factory settings, objects which would previously have been made by one person could now be made by multiple workers using machines.

Some of the artists who we would now call ‘Romantic’ (like William Blake) argued that this shift led to a loss of artistic integrity and creative expression, as mass-produced goods lacked the imaginative power and craftsmanship of master artisans.

See the parallels with AI? Maybe a resurgence of Romanticism, which supports a fundamental belief in the importance of the human creative process, is the only antidote to the robot revolution which is staring us right in the face.

I’ve noted this before, but just to reiterate, here’s my running list of Romantic retrospectives in 2025 so far:

Caspar David Friedrich at the Met, New York; Victor Hugo at the Royal Academy, London; William Blake at the Venaria Reale, Turin; Gothic Modern at Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo.

In cinema, we’ve had the explosive success of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu. Yet-to-be-released are Emerald Fennell's Wuthering Heights; Maggie Gyllenhaal’s Frankenstein; and the shockingly-bad-looking Dracula: A Love Tale (featuring Keanu Reeves).

A recent addition to this list is A Studio Digital’s animated Wuthering Heights, which has just gone viral on Tiktok.

Anyway, the problem with this Romanticism furore is that I don’t actually think it’s very easy to explain what Romanticism actually is. I mean what, exactly, are the similarities between a Caspar David Friedrich painting of a breeches-wearing, hiker in the German mountains and some Gothic, demon orgy by Henry Fuseli? What similarities – if any – do J.M.W. Turner’s kaleidoscopic sun-scapes bear upon William Blake’s tiny, graphic, illuminated prints?

The answer, I think, lies in their common rebellion to the strictures and limits which came before them. The Romantics are not a self-named, self-selecting group like the Pre Raphaelites or the Beat Poets (who all, by the way, loved the Romantics), but they are a wide spectrum of thinkers, spanning from the Georgian to the Victorian era, who were commonly interested in the idea of creation, feeling, and pushing the boundaries of art.

The only way to really get to grips with what that looks like, is by reading what the Romantics actually wrote.

To that end, I’ve curated this list of my favourite Romantic art writing. Happily, all of these works are long-since out of copyright. That means they’re available, for free, online — and I’ve linked them all here in this article.

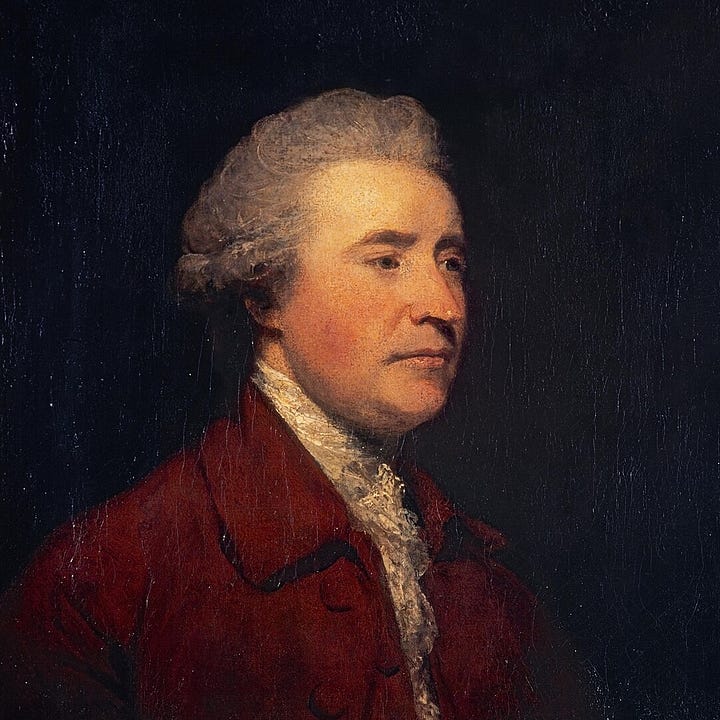

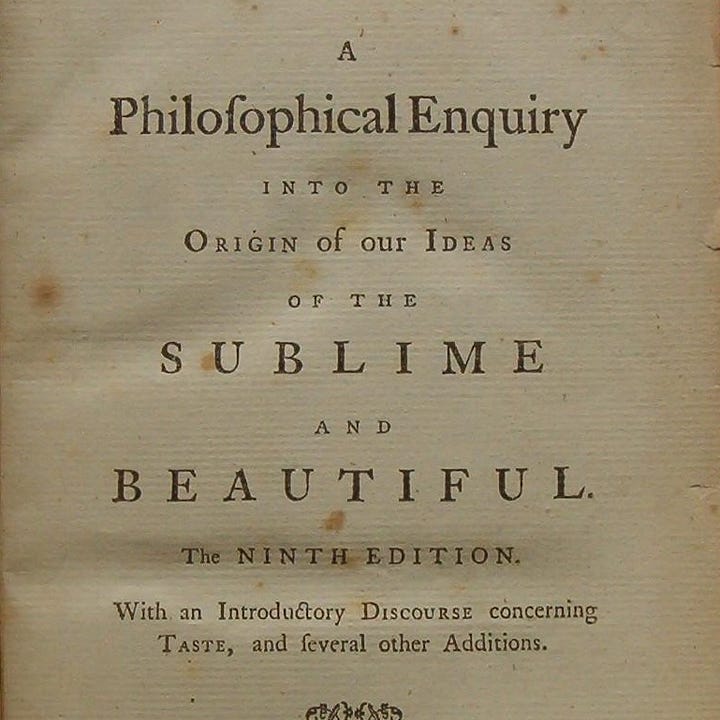

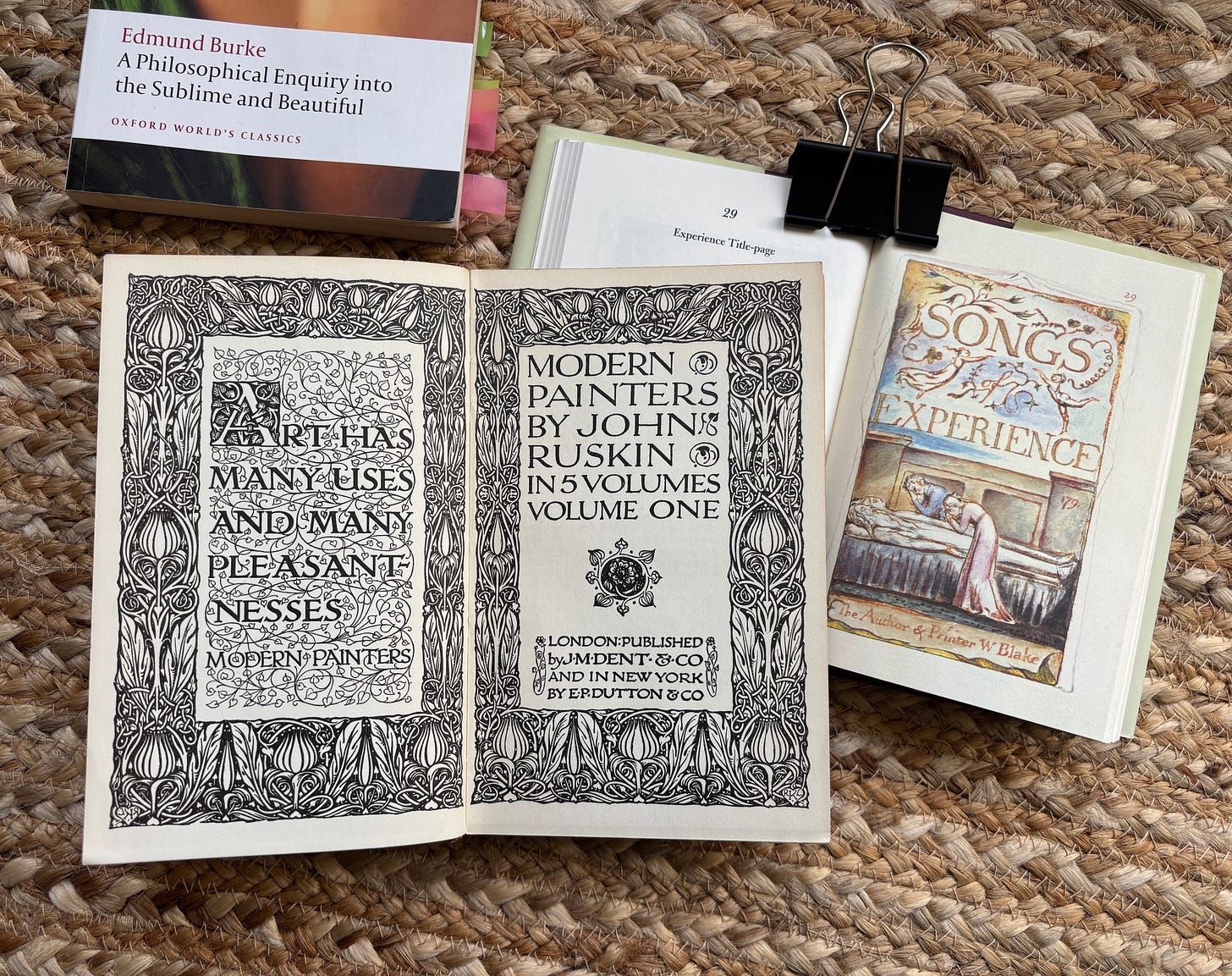

1. Edmund Burke

A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757)

The analogy which I often use to explain Burke’s theory of the sublime and the beautiful is this. ‘The beautiful’ is like sitting in a garden on a warm summer’s day — delicate, harmonious, and pleasurable. ‘The sublime’, by contrast, is like being caught in a storm on a mountaintop — vast, dark, and overwhelming, but thrilling in its power.

Burke’s short, well-structured essay sort of anticipates Romanticism, and even though it is not a work of art theory or art history, it profoundly influenced the artists and poets who would later go on to explore sublime themes in their work.

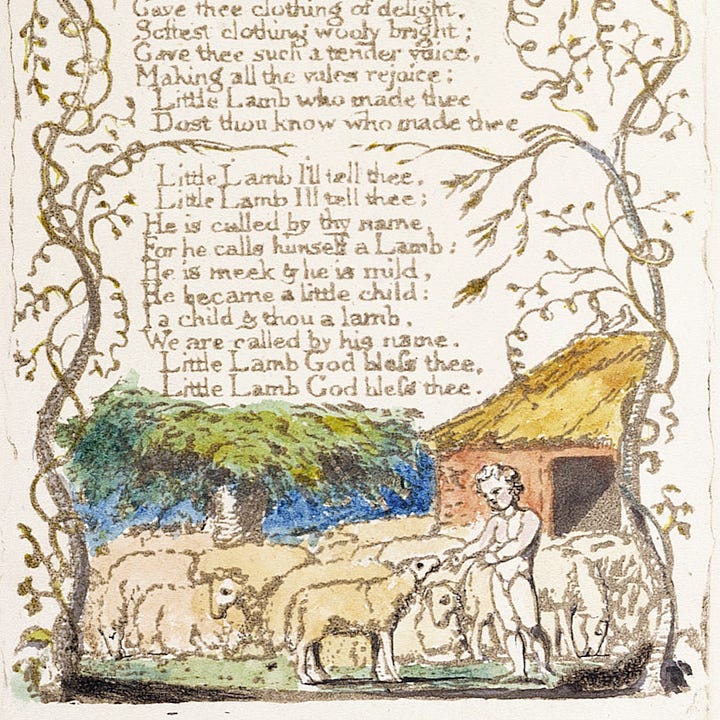

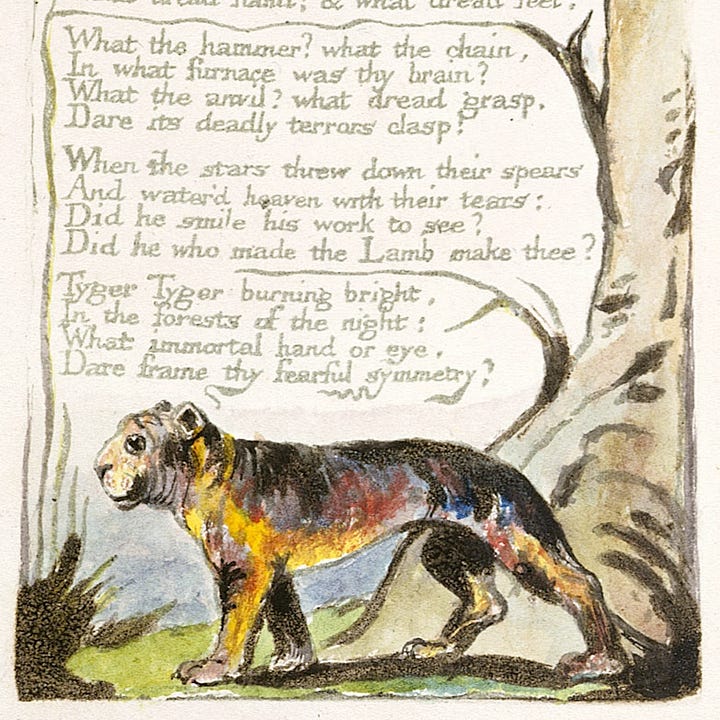

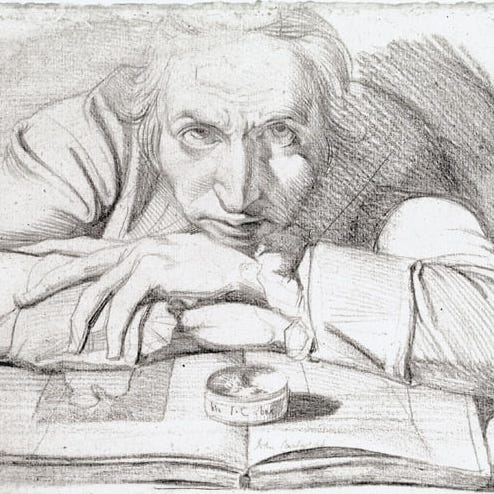

2. William Blake

Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789–1794)

First, let’s get one thing straight: William Blake is an artist first, and a poet second. If you want to understand Romanticism, Songs of Innocence and Experience is essential reading — but to truly grasp Blake’s vision, you must read it in its original, illustrated format.

Songs of Innocence and Experience is Blake’s most well-known illuminated book. It’s an anthology of poems, in the format of children’s stories, which deal with deep and powerful adult themes like death, politics, creation, myth, and faith. It is the format of these poems which make them Romantic, because they are unlike anything which has been created before or since. Blake published these himself, out of his home in Lambeth, London, and they were not recognised for their brilliance until long after his death.

3. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Theory of Colours (1810)

Goethe’s Theory of Colours is a fascinating, if unconventional, exploration of how we perceive colour. It stands in total opposition to Scientific theories of colour which had emerged during the Enlightenment (as in, Sir Isaac Newton), and instead prioritises the psychological and artistic effects of colour. Goethe argued that colours emerge from the interaction of light and darkness and that they carry emotional and symbolic meanings — blue is melancholic, red is intense, yellow is joyful, and so on. His ideas profoundly influenced J.M.W. Turner and, later, Kandinsky.

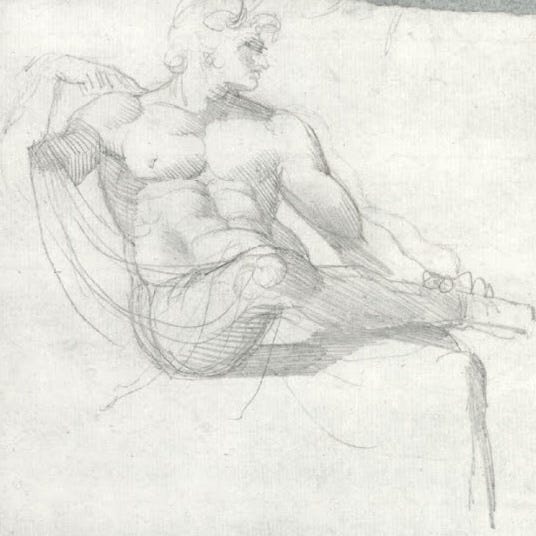

4. Henry Fuseli

Lectures on Painting (1801)

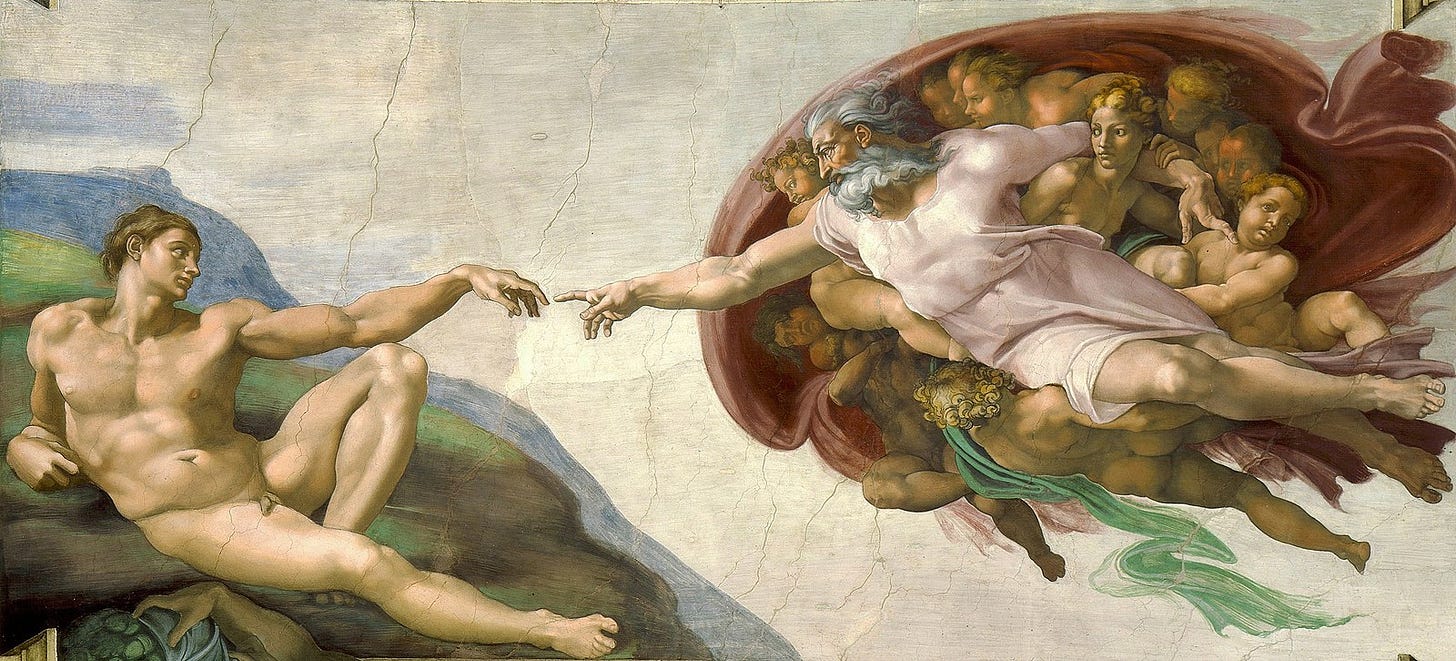

Henry Fuseli delivered these lectures when he was appointed Professor of Painting at London’s Royal Academy in the 1790s. They are dense, but they are astoundingly beautiful. Fuseli was a Swiss-born, eccentric painter. He had a reputation for being enthusiastic and energetic, and he was very inspired by the Italian Renaissance painters (to the point that he actually changed his name from Füssli to Fuseli, to sound more Italian!). Apparently, he used to lie for weeks at a time in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, looking at Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam.

If you read only one of Fuseli’s lectures, it has to be the third one (‘Invention I’). This contains some of the most beautiful descriptions of the Sistine Chapel that have ever been written in English, and they’re all about the creative and divine power of the artist.

Thus in the Creation of Adam, the Creator borne on a group of attendant spirits, the personified powers of Omnipotence, moves on toward his last, best work, the lord of his creation: the immortal spark, issuing from his extended arm, electrifies the new-formed being, who tremblingly alive, half raised, half reclined, hastens to meet his Maker.

5. John Ruskin

Modern Painters, Volume I (1843)

Disclaimer: Ruskin is not, technically, a ‘Romantic’. Romanticism is considered to have sort of ended with the death of Lord Byron in 1827. Ruskin did not publish his first book until 1843. But, remember: the boundaries of artistic movements are not set in stone. Ruskin was profoundly influenced by the Romantics, and this is particularly evident in his early works.

Ruskin wrote a lot. He was a brilliant writer (and actually, a very talented painter too), and well-known for basically setting the tone for Victorian tastes. What’s unique about Ruskin is that rather than looking to the Renaissance or Classical artists, he championed living artists like J.M.W Turner.

In Modern Painters I Ruskin critiques the effects of industrialisation on art (which is a very Romantic thing to do). He argues that true art cannot be mechanically reproduced, but rather must be rooted in direct observation of nature. He also argues that artists should have full control of the creative process, and that art should convey moral and spiritual truths about the human experience.

How might the artist go about this? Well, Ruskin believes that by observing the natural world in an intuitive way, the artist could prompt the viewer’s ‘sympathies’ (ie. make them feel something! Like joy, elation, spirituality, gratitude…).

But I’m not reading Ruskin for the argument. I’m reading Ruskin for the writing. Here’s an extract — a description of a sunrise in Italy:

I cannot call it color, it was conflagration. Purple, and crimson, and scarlet, like the curtains of God's tabernacle, the rejoicing trees sank into the valley in showers of light, every separate leaf quivering with buoyant and burning life; each, as it turned to reflect or to transmit the sunbeam, first a torch and then an emerald. Far up into the recesses of the valley, the green vistas arched like the hollows of mighty waves of some crystalline sea, with the arbutus flowers dashed along their flanks for foam, and silver flakes of orange spray tossed into the air around them, breaking over the gray walls of rock into a thousand separate stars, fading and kindling alternately as the weak wind lifted and let them fall. Every glade of grass burned like the golden floor of heaven, opening in sudden gleams as the foliage broke and closed above it, as sheet-lightning opens in a cloud at sunset; the motionless masses of dark rock — dark though flushed with scarlet lichen, — casting their quiet shadows across its restless radiance, the fountain underneath them filling its marble hollow with blue mist and fitful sound, and over all — the multitudinous bars of amber and rose, the sacred clouds that have no darkness, and only exist to illumine, were seen in fathomless intervals between the solemn and orbed repose of the stone pines, passing to lose themselves in the last, white, blinding lustre of the measureless line where the Campagna melted into the blaze of the sea.

This passage certainly makes me feel something. It makes me feel wonder and excitement. It’s so beautiful, and it makes it abundantly clear why Ruskin is sometimes called a ‘word painter’.

Could AI write that? Not yet. But even if it could… would AI be able to understand it? To feel the raw, elated, emotion behind the words? Of course not.

And that — more than anything — is what Romanticism is all about.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Caspar David Friedrich's figure gazing across the mountain tops could just as easily be contemplating the meaning of death (an equally Romantic theme). Friedrich's mother died when he was seven.

AI will always lack emotion, and that most human characteristic, weirdness. However, emotion is not highly prized. Photography replaced portrait painting, and portrait painting is largely a lost skill.

Tolstoy's War and Peace, serialized in 1865, is an exploration of Romanticism, by subject and example.

Thank you so much for all this, and especially for the reading list!