There is something melancholic about the turn of the century in England.

The Edwardian period follows the self-assured Victorian era. It also precedes the horrors of the First World War. When I think about the 1890s and 1910s, I envision a world on the precipice of collapse. The Empire is growing sick and tired under British pageantry; Ireland is fighting for Home Rule; women (good heavens!) are campaigning for the vote; and Europe is bubbling away in the background like a furious crucible.

All the while, the Edwardians are conducting garden parties in the palace grounds, reading Cicely Mary Barker’s Flower Fairies.

As W.B. Yeats famously said of twentieth-century history: ‘the centre cannot hold’. He’s right: what goes up must come down… and come crashing down the Edwardians certainly did.

It’s a sad story, and one which the King’s Galleries’ Edwardians: Age of Elegance (on until the 23rd November 2025) tells with nuance. This is the first Royal Collection Trust exhibition to tackle the Edwardians head-on.

The governing narrative of this show is one from nineteenth-century glamour and wealth, to twentieth-century solemnity and duty. It’s not just telling the story of an ‘age of elegance’, but really remarking on the end of that age.

The exhibition has a clever, tripartite structure: we begin with domestic life, move on to the royals’ public presentation, and we continue into the fraught space of the Empire, and finish, poignantly, with the horrors of war.

The first room is decorated like an Edwardian interior. It’s a big space, but it doesn’t feel that way. The curation is maximalist, and it’s crammed floor-to-ceiling with treasures that reflect the ornate and slightly whimsical taste of the collectors, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

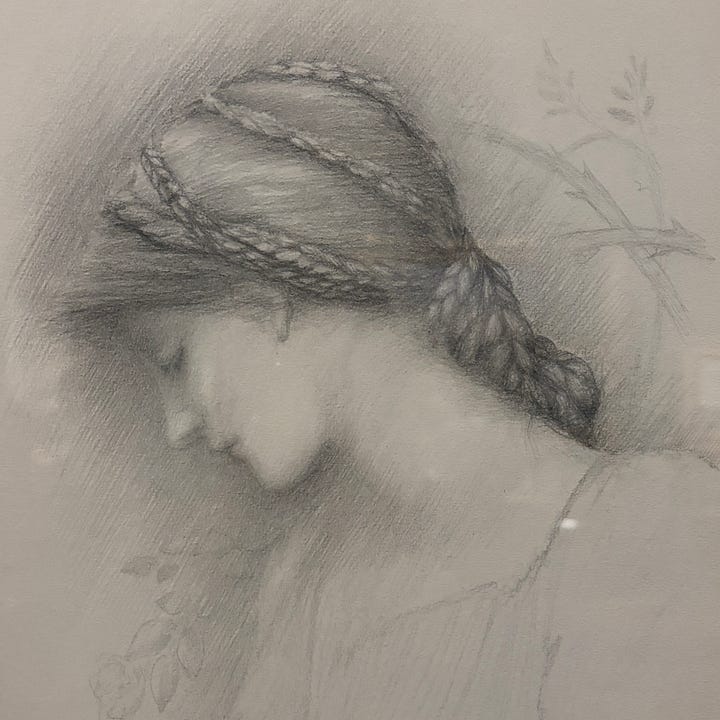

Edward and Alexandra had an inclination for sentimental, Pre-Raphaelite, and very English artworks. They liked Lord Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Edward Burne-Jones. There is a fairy painting by the celebrated, and globally famous, fantasy illustrator Gustave Doré.

The Edwardians also clearly loved (and, really, there is no artistic sensibility more English than this) animal portraits. A particular highlight is paintings and photographs of Caesar, Edward’s fox terrier. There is a fabulously stately lion by Rosa Bonheur. There are countless Fabergé animals – a black turkey, a pigeon, a pig, a crow, and horses – modelled after the menagerie kept by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra at their Sandringham estate in Norfolk.

Overall, though, this opening section is all about the social life of the royals. It’s a testament to aristocratic society, documented not just in paintings and trinkets, but also photographs, furniture, and opulent interior design.

We progress through the gallery into a world of court spectacle. This is the ‘Edwardians’ as they would have been seen by the public: as style icons, immortalised by the finest portraitists of their day (Philip De László and John Singer Sargent), dressed in fine silks and jewellery sourced from far-reaching corners of the Empire.

In the centre of this room there is a glass box. It contains the spectacular coronation gown worn by Alexandra in 1902, which is one of the finest objects in the exhibition. The silhouette and colour (antique gold) evoke the finery of the early-modern court; however, the thousands of tiny golden beads (designed to reflect the new electric lights that had been installed in Westminster Abbey for the occasion) sewn into the dress are emblematic of the modern age.

What is really going on here, though, is an expression of how the Edwardian monarchy maintained public visibility as a stabilising force, especially during a time of profound political uncertainty. Remember: the industrial revolution has brought the UK both great wealth and great suffering. Britain is at the height of its colonial power – but that power is fraught with hypocrisy and fatigue.

This uncertainty is only really present in one painting here: Cecil King’s watercolour of Buckingham Palace under scaffolding in 1913.

The dark, rectilinear drawing smacks of modernity. It’s considerably smaller than other artworks in the room, and yet it carries a truth otherwise concealed by the ceremonial objects which surround it. I don’t read it as a happy painting – it’s rainy and monochrome – but nor do I read the position of the royals in 1913 as especially happy either. The renovation of the palace offers a neat visual metaphor for the malleability of their public status: a status which every single item in this room is conspiring to upkeep.

The Empire section of the exhibit covers the Edwardians’ visits across Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australasia in the 1900s–1910s, and it features a range of artworks acquired as ceremonial gifts, or as souvenirs: an embroidered eucalyptus tree from the women of Adelaide; a carved trowel box from a Māori artist; a finely painted dish from the Bombay School of Art; exquisite watercolours by Mughal artists.

The gallery does a good job of presenting these objects with care, but of course: the Empire is a complicated topic, fraught with wider questions as to the purpose and impact of colonial rule.

The tone is reflective, but the objects also carry the quiet weight of imbalanced power dynamics. One portrait of a young female court performer in India, and another of a young Māori woman mid-dance, I think, symbolise the objectifying lens through which these women (and their countries) were viewed by British artists and imperial rulers.

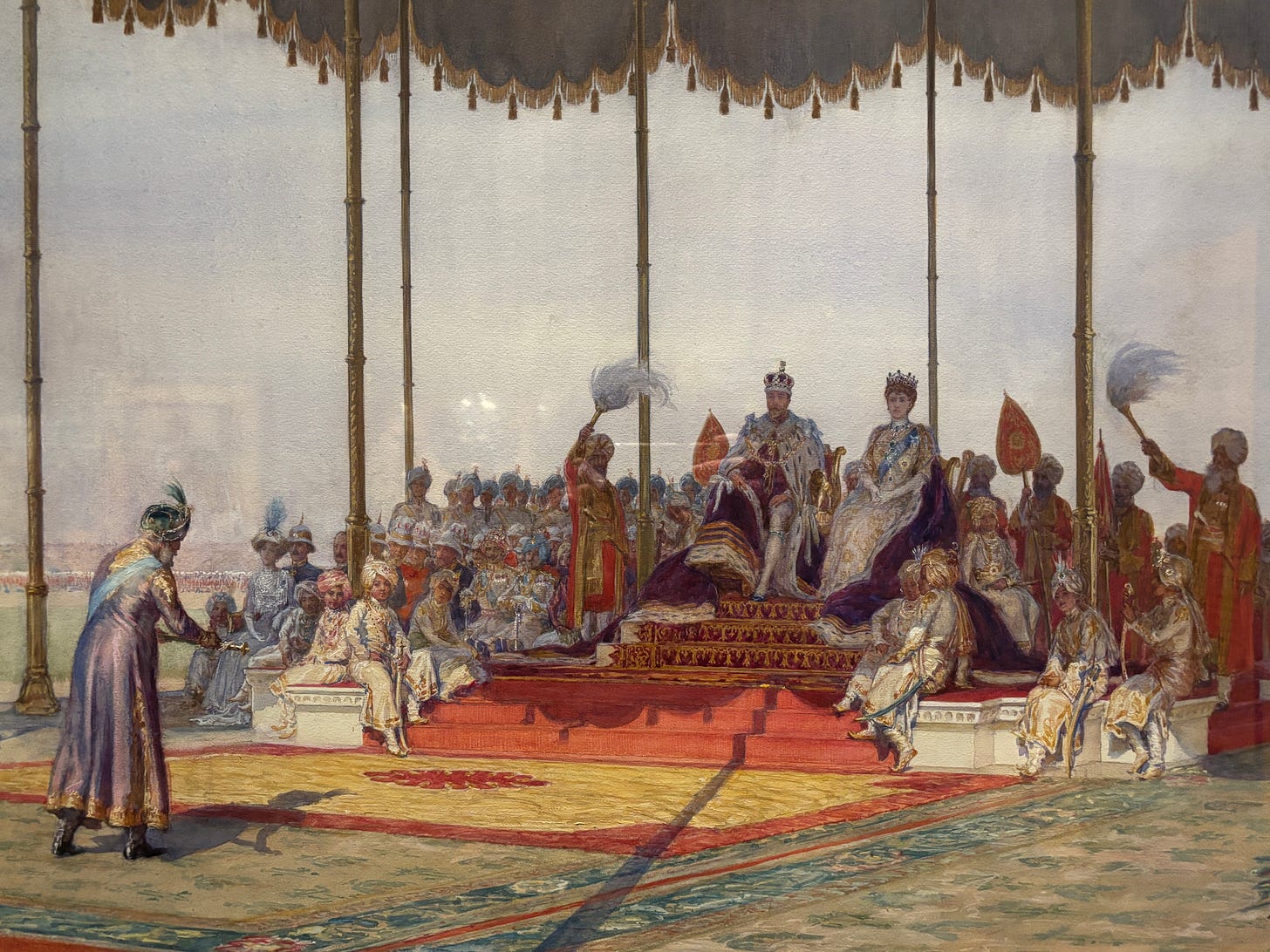

A standout image in this section is a delicate watercolour of the Delhi Durbar in 1911. King George and Queen Mary sit enthroned under a shamiana, receiving the homage of Indian rulers in a scene that draws directly from Mughal court ritual. Although the goal of this royal visit had been to encourage support for the British in India, all it really did was embolden nationalist self-determination. You can see why: the whole performance crowds and supplicates around the British monarchs, who are seated at the top of a metaphor-rich pyramid of stairs.

The exhibition ends, just like the Edwardians did, with a bathetic tapering off. The closing coda of the exhibition — a small room, with a modest showing of First World War paintings — offers a quiet reflection on where the Edwardians left us.

The final picture, The Passing of the Unknown Warrior by Frank O. Salisbury, offers a memorial for the anonymous fallen soldiers. Of course, though, within the context of the exhibition it also serves as a kind of memorial for the ‘age of elegance’ itself. It all starts so well for the Edwardians, riding off the great successes of nineteenth-century technological innovation and domestic stability. Like the rest of Europe, however, they peter out into the mud, blood, and political upheaval of the twentieth century

The role of the King — which, before the war, had only recently been rather glamorous — now became something much more serious. And perhaps that was for the better.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

My thanks to the Royal Collection Trust for kindly inviting me to attend the press viewing of The Edwardians in the Age of Elegance.

This was so interesting to read! I do like your writing style, Rebecca, as it really draws the reader in and whets one’s appetite to learn more about the topic in question. If I lived in the vicinity of London I would definitely go and visit.

This was fascinating! Made me wonder if Edwardian England is the better comparison for the modern USA than Rome is.