The Nihilist Penguin

And its unremitting heroic spirit

I know of no better life purpose than to perish in attempting the great and impossible

— Friedrich Nietzsche

In 2007, the New German Cinema filmmaker, Werner Herzog, released a documentary called Encounters at the End of the World.

At its core, the documentary is an exploration of l’appel du vide (or, ‘the call of the void’). It is a meditation on the absurd, illogical impulse to do the opposite of what is safe, in pursuit of the inarticulable.

The film takes place on the continent of Antarctica. It focuses on the brutal landscape, and on the people and animals that live there. What is it, Herzog asks, that compels certain individuals — from Ernest Shackleton, to geologists and zoologists — into that frozen desert?

In the middle of that documentary, there is a clip, no longer than about 60 seconds, which crystallises the philosophical conundrum at its core. It is a shot of a lone penguin, running away from its colony, in pursuit of the mountains.

We are told, by Herzog, that the penguin refuses both companionship and food, and is apparently suicidal. With 5000 kilometres ahead of him, he is heading towards certain death.

Many people have resonated with this penguin. In fact, millions. This clip has gone viral across social media, uniting sportspeople, artists, cultural commentators, and comedians alike.

So, what is it that makes this clip so effective? And why has it struck such a chord, now, twenty years after its conception?

1. Romantic visual language

It’s not so much the penguin’s death drive which people are responding to. Instead, the power of this clip lies in Herzog’s interpretation of the penguin’s independence from the colony. It becomes a heroic, existentialist symbol.

The visual language here draws from our cultural understanding of icy, barren landscapes. In fact, the emotive power of the frozen wilderness was one of Herzog’s main motivations for setting the documentary in Antarctica.

In art and literature (for instance, in Robert Frost’s 1923 poem, ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’) the motif of the snowy wasteland has come to represent poetic feelings of isolation and transcendence.

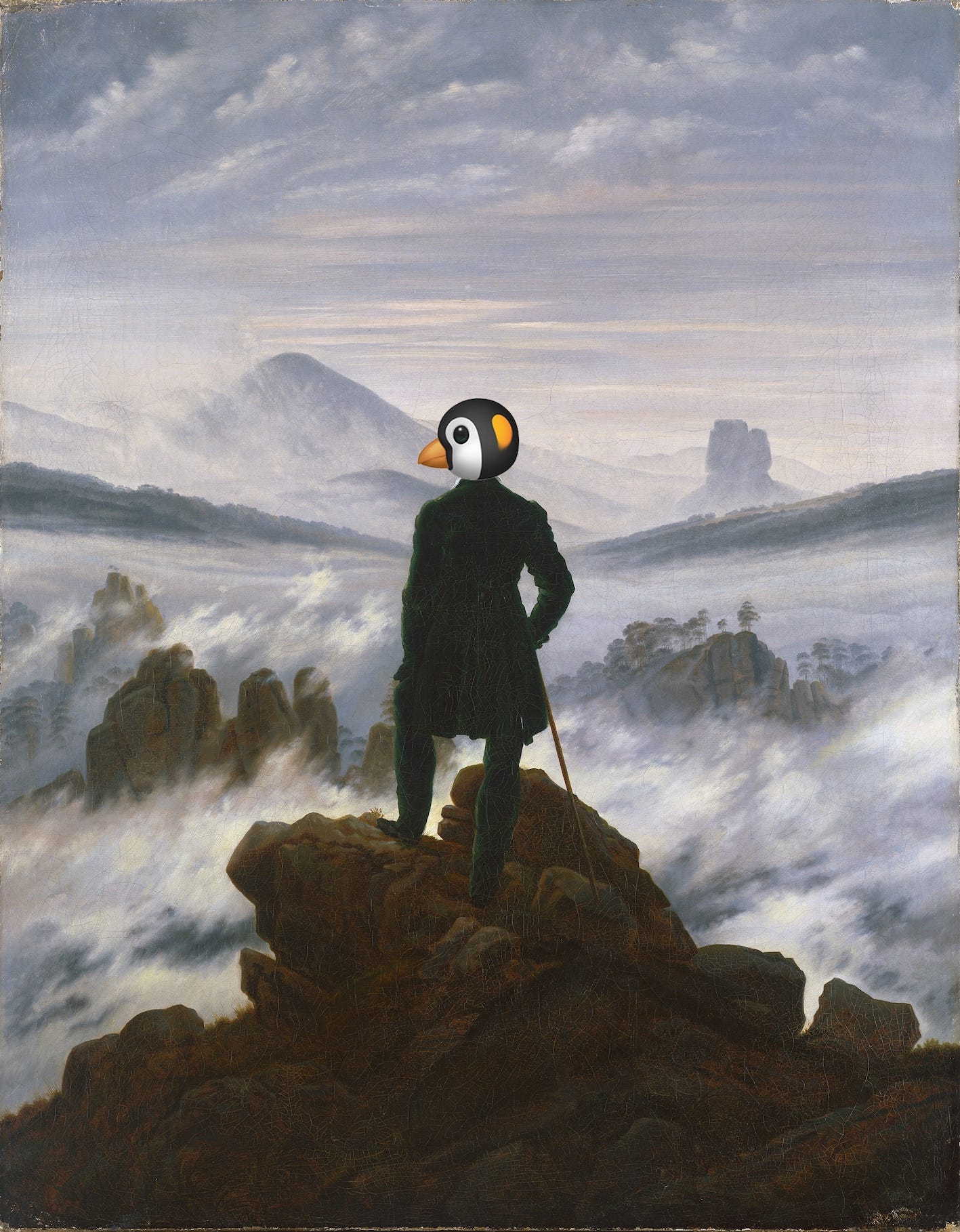

This Romantic setting arguably found its most powerful proponents in German art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Herzog was likely aware of this. His shots of the lone penguin echo the sublime vistas of the landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich, who I wrote about last year.

Those mountains where the penguin is running… they are the same symbolic mountains from Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.

In Herzog’s documentary, as in Friedrich, those mountains represent truth, infinity, and the sublime. They are dangerous and bleak; but, according to Herzog’s framing, that is precisely what makes the penguin run towards them.

He represents the pursuit of meaning at any cost.

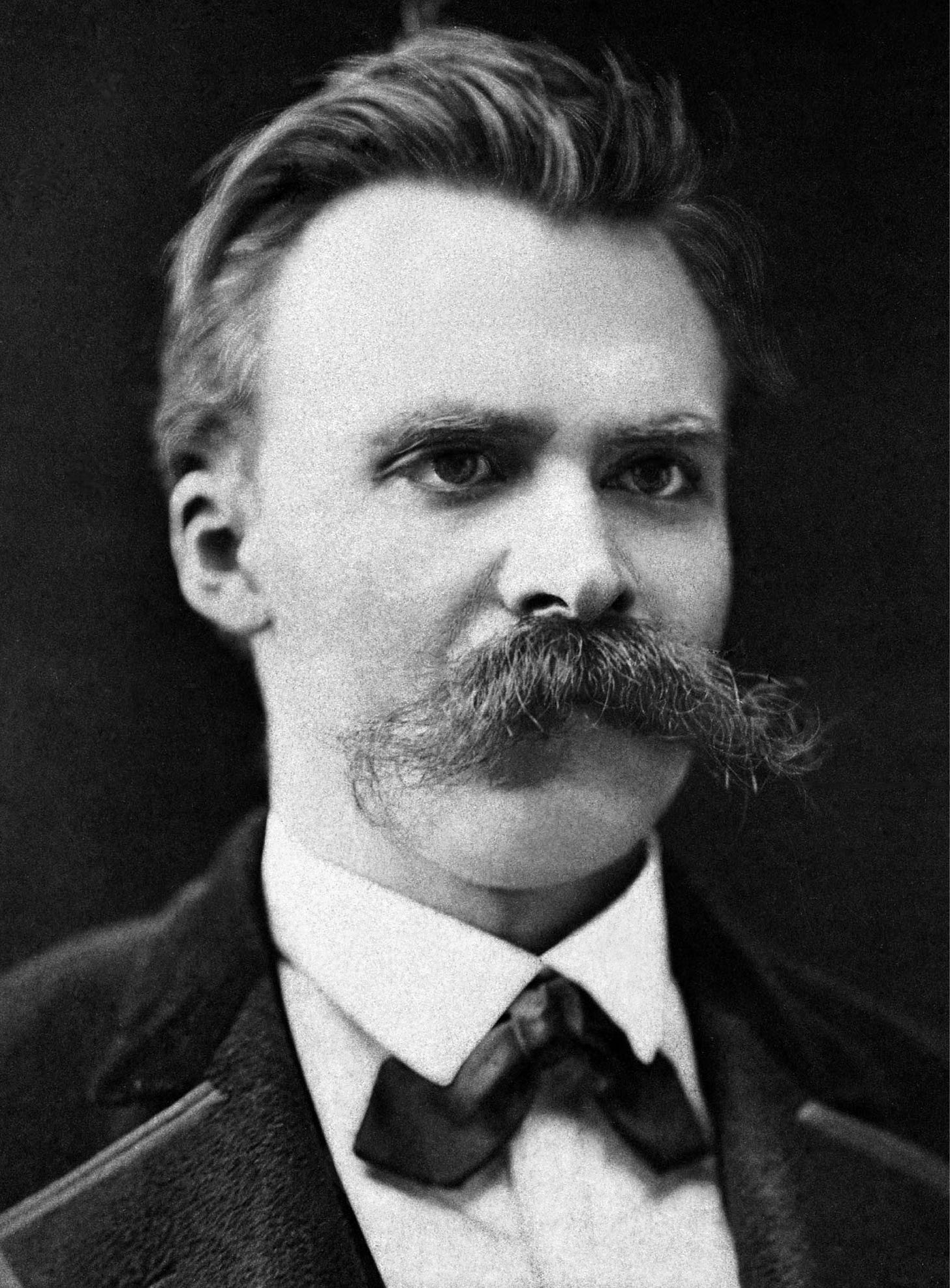

2. Nietzsche

There is an important link to be drawn between Herzog’s penguin and the works of Friedrich Nietzsche (not in the least because everyone is calling it the Nihilist penguin)…

In the most simple terms, Nietzsche’s idea of nihilism is that traditional sources of meaning, like religion, have collapsed (this is why he is famous for saying ‘God is dead’). It can be approached in two ways.

Firstly, there is passive nihilism, where you resign yourself to the meaninglessness. In recognition of the pointlessness of existence, you say ‘whatever, I give up’, and live out your life, for instance, as a depressed penguin in the colony.

Secondly, there is active nihilism. This is where, in response to the recognition of the void, you say, ‘life is meaningless, and because life is meaningless, I reject the colony and I embrace fear, in pursuit of something higher. I create my own meaning.’

That penguin is an active nihilist — or, at least, he is framed by Herzog as an active nihilist, which is equally as powerful.

What makes the penguin Nietzschean is not that it is suicidal (in fact, Nietzsche would reject suicide), but rather he refuses to live passively. The penguin literally dives head-first into the void.

The reason why this penguin resonates so powerfully is because it has departed from its nature. Nietzsche’s philosophy is all about going beyond our nature — beyond moral and social categories — into radical acceptance.

One of the most affecting parts of the penguin video is when the penguin looks back, forlornly. He knows what suffering awaits him: but he chooses it anyway. It shows us that we too might be capable of breaking away from the herd.

3. But why now?

We will never know why the penguin refused to conform. Perhaps the penguin was insane, or lovesick, or exiled from the colony for other, unknown, penguin reasons.

However, many would say that the penguin’s motivations ultimately do not matter. In absolute terms, the penguin’s decision to defy nature inherently contains a nihilistic beauty. Herzog has humanised the penguin for us, with his voiceover, and with his cinematography, and brought out the extant Nietzschean spirit.

But why is that message going viral right now?

It might have something to do with the allure of radical nonconformity in a world which is increasingly surveilled, and over which we feel we have less and less control.

Moreover, the penguin is a symbol of alienation. Since the pandemic, which saw the closing of ‘third places’ and increased usage of online media, it’s true that many of us have felt increasingly isolated. Maybe those who feel alone recognise themselves in that penguin.

But my favourite interpretation of the penguin resurgence is that it forms part of a wider trend for ‘New Romanticism’.

With the digital revolution, and global political instability, are we beginning to lose faith in the established order? Possibly, we are now turning to things which make us feel something — like spirituality and art — rather than to things which are technical, optimal, or scientific.

Romanticism offers us an alternative to certainty. It first came about in the wake of the French and American Revolutions, just after people had watched society crumble before their very eyes. With the collapse of the old regime, artists began to search for new forms of meaning.

Romanticism is interested in the ineffable, the spiritual, and the importance of personal experience. It cannot offer us order and reason — only blind faith, and blind feeling.

Herzog’s penguin is an active nihilist, yes, because it marches into its ‘certain death’. However, it is also Romantic. Remember: that penguin it isn’t only heading towards death; it is heading towards the mountains. And while those mountains are inhospitable, but they are also full of beauty, and spiritual truth.

Those are things worth pursuing, even if you’re just a penguin.

If you’d like to support my work, but can’t commit to a full-time subscription, why not leave a tip?

Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my TikTok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates.

Incredible. Honestly. Also, it's nearly 1PM on a Monday and I'm crying about a penguin, so thanks

I think secular modern science has given up too easily on spirituality, and it shows. Maybe now (or soon), as AI can do rational, logical thinking better than us, we'll finally invest some resources in the other things that make us human.