Spoiler Warning: The following piece contains major spoilers for the Apple TV series ‘Severance’. If you haven’t seen it yet, consider returning to this article after watching.

Has anyone else noticed the paintings in Severance?

Let me backtrack a bit. Severance is a dark, mind-bending, dystopian drama series produced and directed by Ben Stiller. The first season was released in 2022 and the second season is currently airing, weekly, on Apple TV. The narrative centres around the main character, Mark, who is a sort of ‘everyman’ – a besuited, project-manager-type, played empathetically by Adam Scott.

Mark is an employee of the large (ostensibly evil) corporation, Lumon. He works on the ‘Severed’ floor of Lumon, which means he has undergone a procedure to separate his work memories from his real-life memories. What does that mean? Well, it means that Mark, and everyone else who works on the Severed floor, has two separate identities: the ‘innie’ (the employee identity, who is activated only when they enter the Lumon building) and the ‘outie’ (the original self, outside of work).

This show is brilliant. Severance is a satire (albeit, a dark one) on workplace culture. It’s satire on jargon, on ‘company policy’, on bureaucracy. More widely, it is an allegorical critique of authoritarianism, on propaganda, and brainwashing. The story is compellingly driven by dangling in front of us, the view, the possibility of Mark resisting that authority, however vain his efforts might seem.

If you like Severance, you’ll enjoy Franz Kafka’s The Trial (1925), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985).

Anyway, one very interesting feature of the Lumon indoctrination machine is artwork. The company places paintings on the walls of the office – pastiches of paintings in the real world – in which they substitute the company founder, Kier Eagan, for the main character.

The characters of the show engage with these paintings in a number of ways. One of the characters, Irving (John Turturro), strikes up a friendship with another worker from the department which hangs the paintings, Burt (Christopher Walken). Their meeting is the first time the paintings are really brought to our attention.

The scene is unsettling. Muzak is playing. The painting is the only decoration in the white room. It depicts the figure of Kier, dressed in Biblical garb. He is backlit by a burst of light, brandishing a whip in his right hand. Figures emerge from the darkness at the right-hand bottom side of the canvas: two penitent women, one young, one old; one court jester; and one ram, dressed in human clothing (sidenote: goats are a motif we get elsewhere in the show, and it’s not yet clear what they’re a metaphor for yet).

This artwork combines features from Baroque art. It reminds me of paintings like The Seven Works of Mercy (1607) and The Conversion of Saint Paul (1601) by Caravaggio, and The Resurrection (1635) by Anthony van Dyck. This is a style of painting that is all about drama and religiosity: dark, moody backgrounds, bright lights, and powerful displays of emotion.

This is the dialogue exchange between Irving and Burt regarding this painting:

‘That piece hung in the perpetuity wing for many years’

‘It broke my heart when they took it down’

‘It’s better here. It’s calming.’

‘It’s rare to meet… a sophisticate.’

To me, nothing about this painting is remotely calming (nor especially sophisticated… compared with Caravaggio). But, I am also not a salaried, Severed employee of Lumon. And this is the whole point of the scene. It’s a commentary on the nature of propaganda. However unsettling it might seem in isolation, or in retrospect, propaganda is highly effective on indoctrinated individuals. For Irving and Burt, then, the painting is calming because it reinforces the hierarchy, morality, and omniscient power of the company. ‘Omniscient’ is certainly the right word here: there are cameras everywhere on the Severed floor.

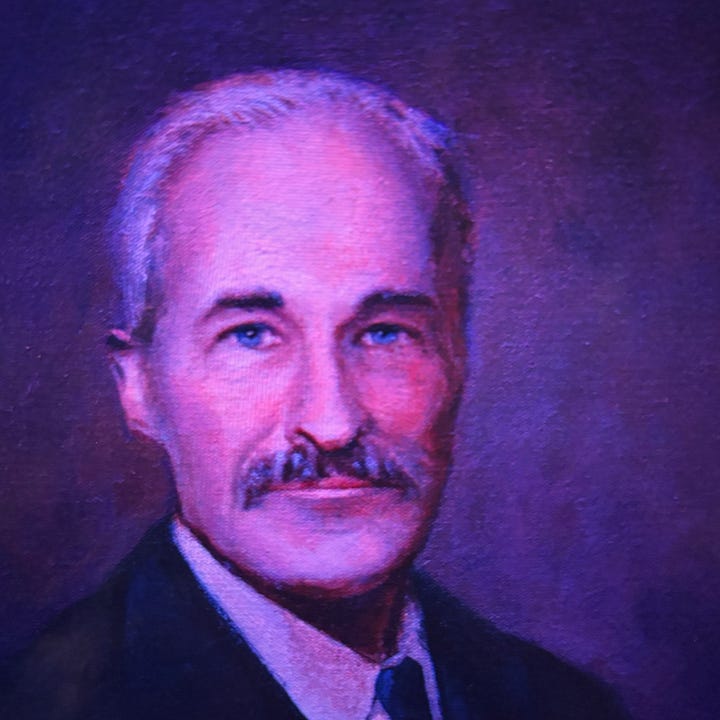

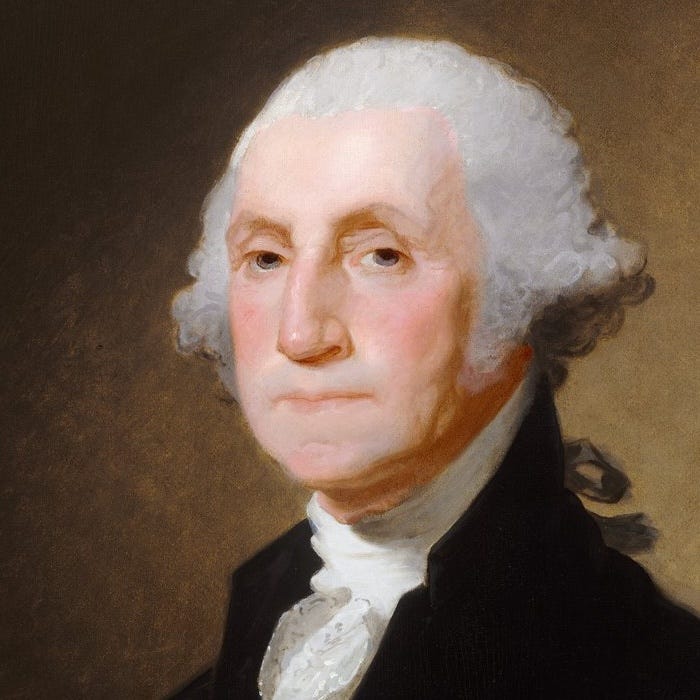

This omniscience is subtly alluded to throughout the first season by the presence of a portrait of Kier, placed in the centre of the office where our main character works every day. This is a sort of presidential, nineteenth-century style portrait – something like Gilbert Stuart's George Washington (1821), or John Singer Sargent’s Theodore Roosevelt (1903). We’ve moved, then, from seeing Kier depicted as a divine Baroque figure in the first picture, to a more stately governmental one in this portrait – again, omniscient.

Interestingly, in a later episode, when Irving becomes more critical of the company, he stares angrily at this portrait, before squashing a boiled egg in between the pages of the worker manual – a sort of Bible for the Severed workers, written by Kier. I think this is the Severed equivalent to blaspheming.

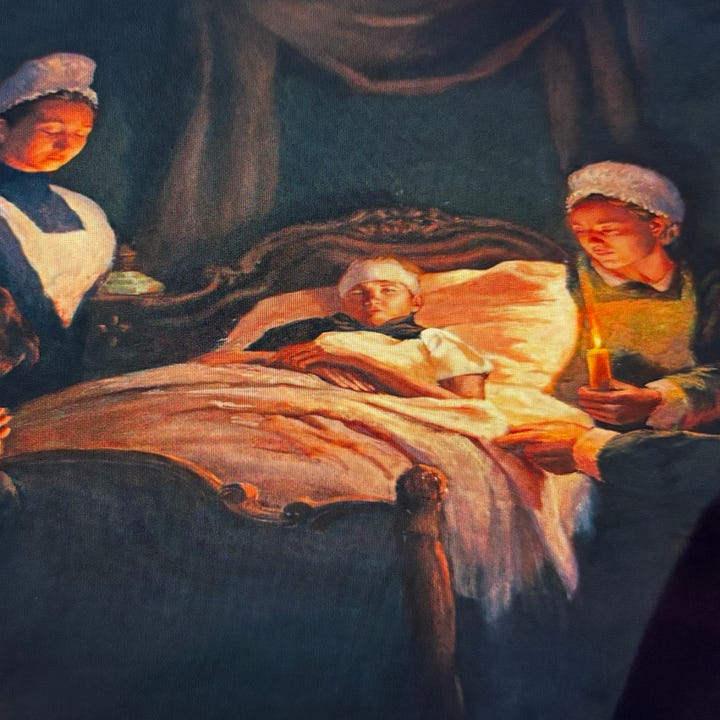

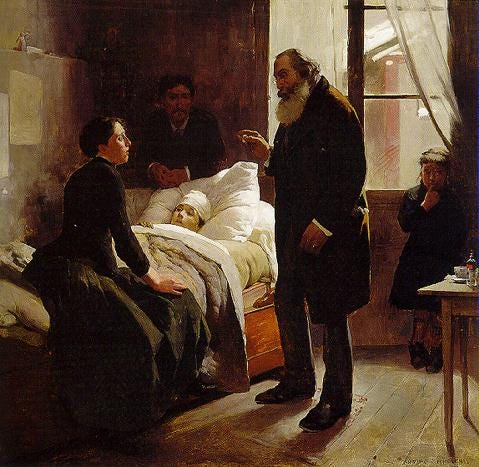

We see many other versions of Kier in different paintings, revealed slowly throughout the show. One of these is a sort of copy of Arturo Michelena's The Sick Child (1886). This is supposedly a depiction of Kier’s childhood (from a series of paintings which the workers obliquely refer to as ‘The Kier Cycle’). It is what we might call a ‘genre scene’: a painting of mundane, daily, lowly life (as opposed to high, grand subjects like Gods and myths). It is intimate and melancholic, emphasizing Kier’s humanity and vulnerability. At least in the context of the propaganda machine at Lumon, this painting likely serves to make Kier relatable to his workers.

Talking of propaganda, let’s talk about the painting recently revealed in the new series. It’s a new addition – presumably a visual metaphor for the events which happened last season (where, in summary, four workers rose up against the powers-that-be). Kier, again with a halo of light, is depicted with a bloody sword. He kneels and pats the heads of four workers, maybe forgiving them, knighting them, or perhaps even threatening them.

The composition, with the figures kneeling before a central authority figure; the red and gold colour palette; the background buildings, with their Cubist, Brutalist, or early Futurist look, make this highly reminiscent of Soviet and fascist propaganda posters.

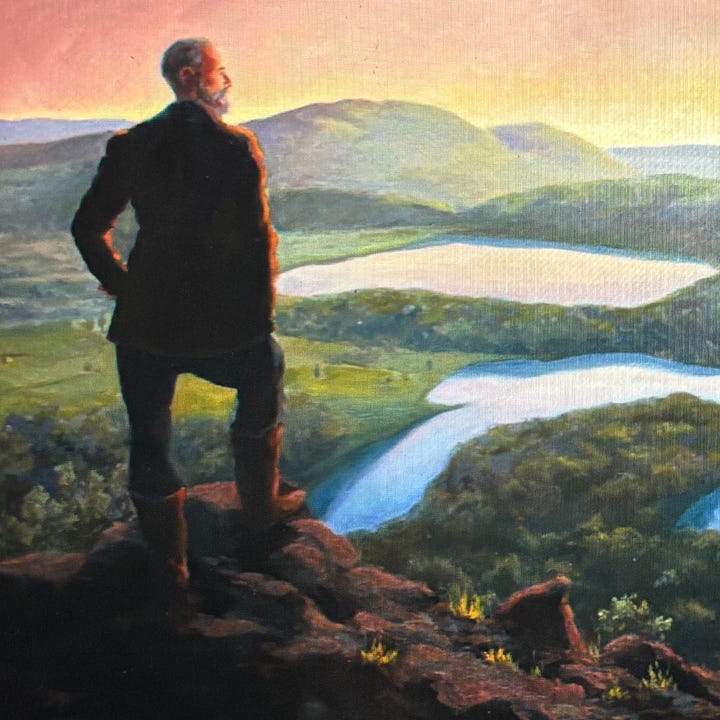

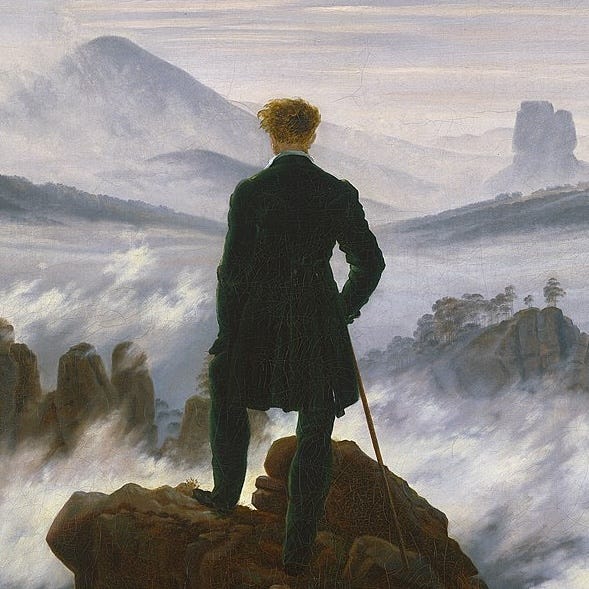

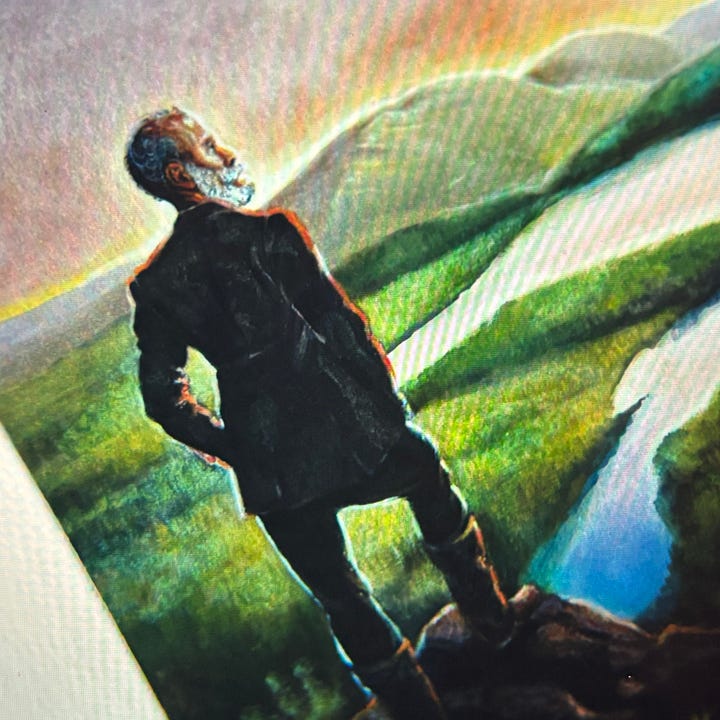

But this very obvious link to very obvious propaganda isn’t the only way indoctrination operates in the paintings at Lumon. For instance, there is a clear copy of Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1817), which portrays Kier as a Romantic trailblazer. Rather than placing him in a position of dominance over his workers, as the other paintings do, this one gives a sense of his personal, poetic, freedom.

‘Is it terrible to say,’ whispers Irving, ‘that I don’t particularly care for that one?’

‘Yes’, replied Burt, ‘it makes me nervous too.’

What about this painting makes them uncomfortable, particularly when they found the Baroque one ‘calming’?

Maybe it prefigures Irving’s growing disillusionment with the company. But, actually, I think the reason is something else. My suspicion is that this scene illustrates how the employees are seemingly more at ease with depictions of obvious, direct power than with vague, ideology. These severed workers are taught, from the moment of their severing, to accept hierarchy and control. Violent, omniscient Kier is easy to understand. Ambiguous, Romantic Kier is perhaps a bit too mysterious, or a bit too isolated. Maybe the adventuring spirit of the painting plants a seed, a desire, to adventure outside the boundaries of the Severed floor. Unclear.

Anyway, keeping on the Romantic line of thought, there is one painting in the show which does not feature Kier. It is a gruesome depiction, in the style of Francisco Goya’s infamously disturbing ‘Black Paintings’, of an interdepartmental fight between the Lumon workers.

It’s used as a plant, to discourage the characters from fraternising with other employees. This image is one way in which Lumon looks to suppress the revolutionary spirit which underlies the entire show, although it seems to have the opposite effect.

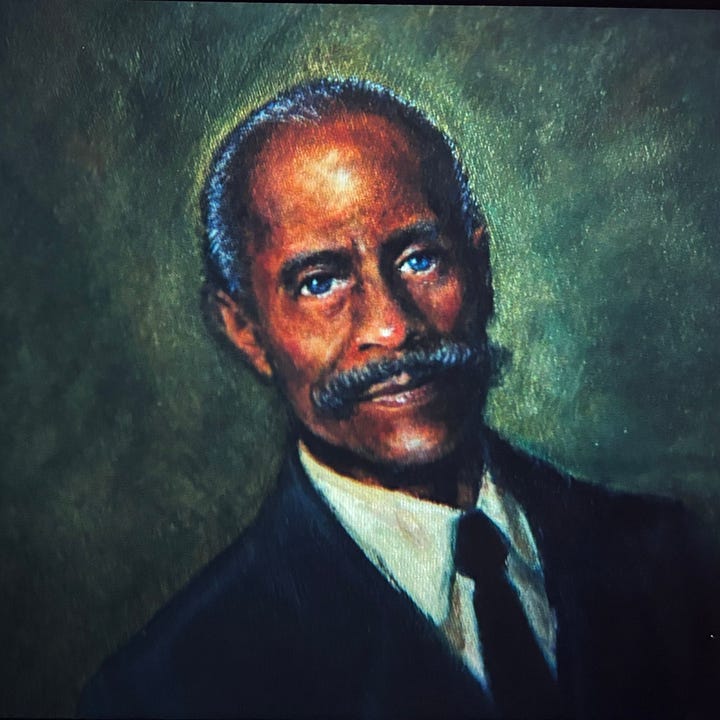

To bring us up to date, I’d like to finish on the scene when the supervisor, Milchick (Tramell Tilman), is promoted. To mark his ‘ascendance’, he’s gifted all of the Kier paintings, with himself, Milchick, painted into them. This scene carries weighty tensions about race, power, and corporate myth-making. This moment is an example of performative, artificial diversity: a hollow attempt to make Milchick feel appreciated by the company, but which instead results in his alienation.

It represents a critique on how real-life corporations tend to only change surface-level imagery, or branding, rather than addressing deep-rooted power structures relating to, for instance, race, gender, sexuality, and religion. The point is this: making Kier look different doesn’t change the system of control. Milchick gains no real power, the severed workers remain trapped, and the entire gesture ultimately serves only to reinforce Kier’s cult of personality.

Overall, I think the use of paintings in Severance is extremely effective. Sparsely set against the stark white, hospital-like corridors of the office, they offer visual beacons for the workers – and for us, the viewers – which offer us little tidbits into the mysteries of Lumon.

It’s interesting too, I think, that these paintings mimic many different schools and periods… from sixteenth-century Baroque, to twentieth-century Soviet art. The company seems to be crafting a narrative for the workers where their semi-mythical founder, Kier, spans centuries. This, I think, mirrors how authoritarian ideologies borrow from different eras to construct their own mythologies.

Equally, though, what Severance implies is that if art can be used to control, it can also be used to question and challenge. It is not insignificant that Irving’s outie (who, because of the ‘Severance’ procedure, has no idea what his innie does inside the company) is a painter. The works he paints are obsessive, dark visions of the world inside. His method of painting, too, is frenetic, expressionist, and abstract – very unlike the Classical, figurative, and propagandist paintings inside the workplace. It’s a rebellious way to paint. And it might prefigure a workers’ rebellion to come. Let’s see.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions in London. I am also active on TikTok.

Omg I was planning on publishing a piece on the music in severance this afternoon—good timing!!

This is a really good piece on the best show around at the moment. I had spotted the Friedrich and Goya-esque paintings but didn’t clock all the others: great eye and great analysis too.