The vernal equinox took place a month ago, on 20th March, and (in the U.K. at least) we’re firmly in the throes of spring. The asparagus are sprouting, the daffodils are blooming, sheep are lambing, and Robert Browning’s poetry has bizarrely come into fashion again – ‘Oh, to be in England / Now that April’s there’ (etc.).

You’ve heard of Flaming June (or, at least, you will have if you’ve been here a while) – but what about her younger, fresher, sister? I’m talking about Flora, the Roman goddess of spring.

Flora is something a bit like the Greek goddess Persephone, but a little more fun. Flora is much more closely related to nature (and she’s not married to the god of the underworld). The name ‘Flora’ comes from the Latin word ‘flos’, meaning flowers, and she really comes into her own in late April and early May.

Right now is Floralia season, baby!

Just ask Substack’s resident master of ceremonies, Cosi’s Odyssey, who will be hosting an all-day Floralia festival on the 3rd of May in London (tickets here).

Although you might not have heard of Floralia before, I imagine you’ve come across it on at least one occasion. Do you recognise this picture?

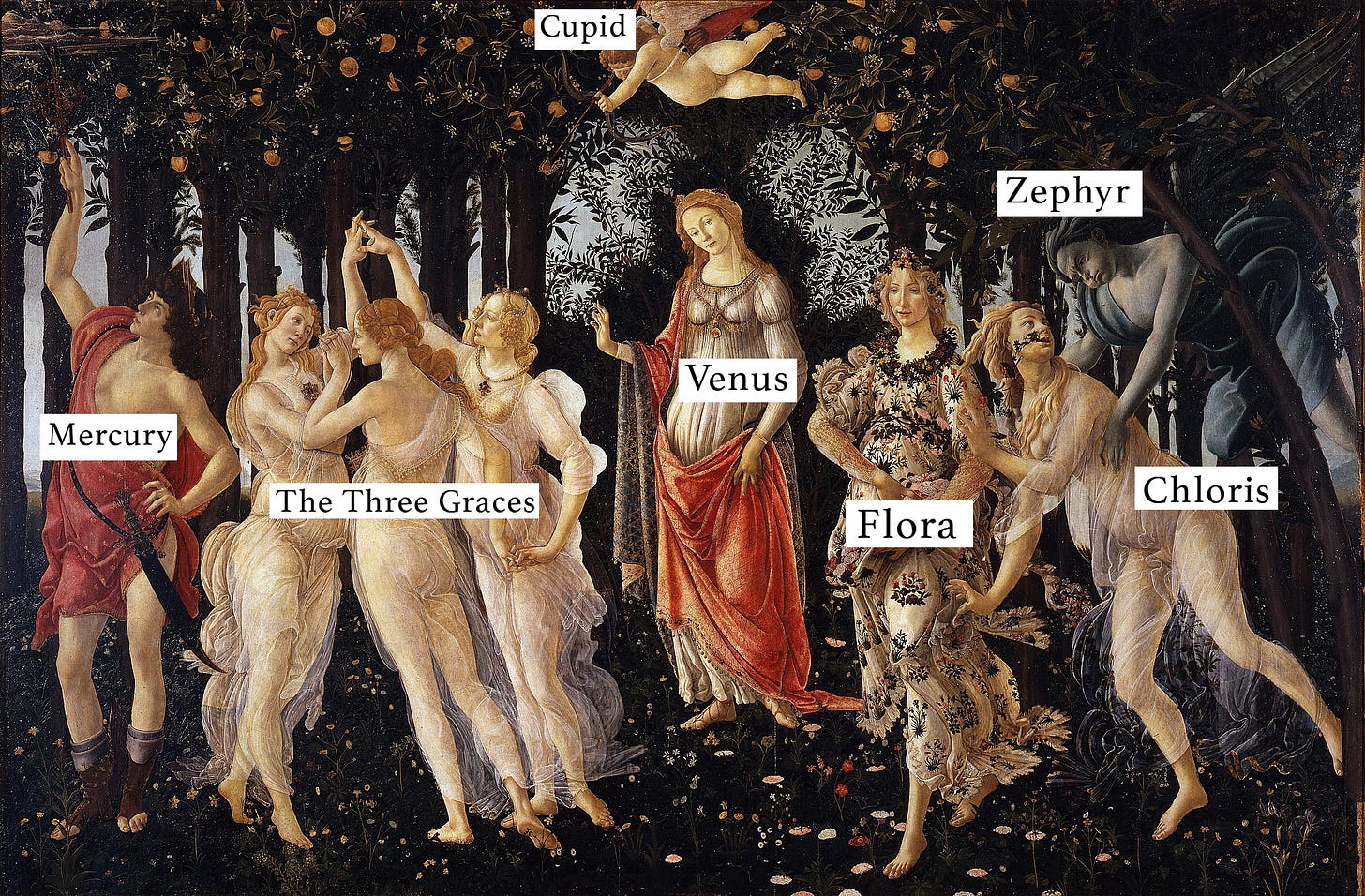

This is Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera. It’s an early Renaissance painting dating from the late 1470s to the early 1480s. It’s in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, and it’s among the most famous works of art of all time – perhaps only slightly less well-known than The Birth of Venus (yes, Botticelli did that one too).

To understand what’s actually happening here, we need a bit of historical context. Primavera is an Italian Renaissance painting – and ‘Renaissance’ means ‘revival’. Art historians use the term to describe the flourishing of art and literature in (what we now call) Italy during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It marked a renewed interest in Classical culture: in Greek and Roman philosophy, architecture, mythology, and aesthetics, all filtered through the lens of late-medieval Christianity.

So, when Botticelli painted Primavera he was painting an idealised, poetic ‘revival’ of Roman mythology. It’s a Renaissance artist’s idea of pagan gods partaking in a festival. It’s kind of like if a British artist today was to paint a picture of a folk festival, with goblins and fairies dancing in the background. It’s a celebration of past beliefs and traditions, seen through a retrospective lens.

Scholars think that Botticelli’s Primavera was likely intended as a wedding gift for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici.

Lorenzo was a member of the Medici. They were the powerful ruling family of Florence, on and off from the 1430s to the 1730s, and infamous patrons of the arts. Without the Medici, we wouldn’t have had some great Renaissance masterpieces. If you want to learn more about the Medici I would highly recommend this book.

Botticelli’s Primavera has a mythological, pagan subject. That means it would not have been hung in a religious space — like a church or chapel — but instead in a casual environment. Perhaps a villa. It would have been a source of delight and discussion.

The painting is full of visual jokes which relate to the Medici family, which would have been endless fun for the patrons to chortle over. For instance:

The oranges in the trees above the dancers are a reference to the Medici coat of arms, which has five orange balls.

The presence of laurel trees are a pun on the name ‘Lorenzo’ — which means laurel-crowned.

The painting features Mercury, god of doctors (among other things). ‘Doctors’ translates to ‘medici’ in Italian — !

But maybe we’re losing sight of the wood for the trees. Let’s zoom out from the details, and establish who we’re actually looking at and what they’re doing. It’s only by understanding the visual narrative of Primavera that we can really answer the governing question of this essay: just what does spring look like, and how does it relate to the way we still celebrate the coming of springtime, in the present day?

Let’s start with a who’s who, from left to right.

The figure on the far left, dressed in a red toga, is Mercury: the messenger of the gods. In this painting he’s a symbol of rationality and order. His back is turned to the partying guests, and he’s making sure that the weather stays nice, which is why he seems to be swatting away clouds with a wooden rod.

Next over is a group of three beautiful, gossamer-clad, dancing women. They are the Three Graces, Venus’ companions. Botticelli has painted them according to Renaissance ideals of beauty: golden hair, long necks, high foreheads, clear complexions. Their names are Voluptas, Castitas, and Pulchritudo: meaning, Pleasure, Chastity and Beauty. The interwoven lines of their bodies, the transparency of their clothing, their dynamic gestures: all of these show Botticelli’s mastery of his medium (tempera).

Overseeing these three graceful companions is the calm, neutral Venus (at least… we think it’s probably Venus). She stands in the centre of the image, ensuring that her guests are having a good time by giving us a welcoming gesture (‘hello!’), beckoning us to come join in the party.

Venus’ chaotic son, Cupid, hovers in the bushes overhead. He’s poised to shoot one of the Graces with his arrows of love…

Very naughty! Cupid, get down from there!

Then, on the right-hand side of the painting, we get to the meat of the narrative.

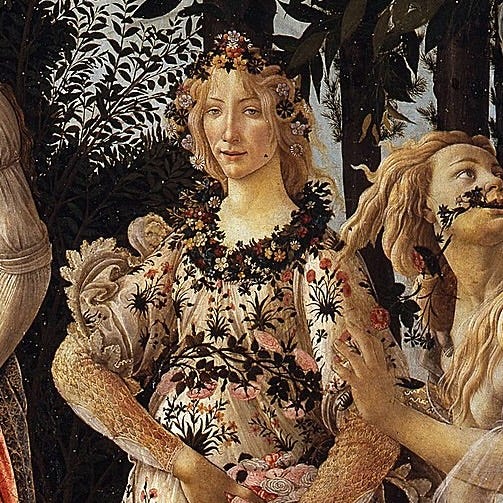

The woman to Venus’ right, dressed in flowers, is Flora. The figure next to Flora, casting a worried look over her shoulder, is Chloris, a wood nymph. Chasing Chloris, on the far right, is the blue-tinted Zephyr: god of the west wind. The whole scene represents the story of spring, and it’s an ambivalent one, to be sure.

So, we read the group from right to left. Zephyr has taken a shine to the beautiful Chloris, and is chasing her, with the hopes of making her his wife. Eventually, he catches her, which initiates her transformation (as is often the case with nymphs). So, Chloris turns into Flora.

This story derives from a poem (‘Fasti’) by Ovid, and we know this because of the strangely blueish colour of Zephyr’s skin, which is alluded to in that poem. This is where Chloris’ name comes from: ‘khloros’ (green).

It’s a strange and slightly uncomfortable story, because Flora is born from what is essentially an act of violence. Botticelli doesn’t shy away from this. In fact, this uneasy transformation gives the painting its depth: spring is not just joyous; it’s also unsettling, a season of disturbance, growth, and metamorphosis. Remember: Zephyr is the west wind. He represents winter, primal desire, and change — and it’s only from his pursuit that spring can really manifest.

The mood, symbolism, and characters in Botticelli’s Primavera echo the spirit of Roman Floralia celebrations, and of the coming of springtime more generally.

Venus, the Three Graces, and Flora signify the harmony and beauty of the season; however, the presence of Cupid, Zephyr, and his victim Chloris impart a theatricality and mischievousness to this painting.

Spring is full of mischief: sexual awakening, flirtation, twitterpating. This is why the Roman Floralia festivities would involve pantomime, comic theatre, dancing, and bawdy humour — all of which highlight the frivolity of youth and springtime.

By drawing on Roman mythology, and placing it within the context of fifteenth-century Florence, Botticelli set the blueprint for what Spring (or, at least, the goddess Flora) would look like in Western art.

She is deeply connected to Renaissance ideals of beauty, fashion, and greatly influenced the way that later artists — for instance, the pre-Raphaelites –— envisioned Classical goddesses. It helped popularise the association of springtime femininity with flowers, flowing dresses, and florals… all of which have since become staples of festival culture.

Florals…? for Spring? Groundbreaking.

Final reminder: if you’re keen to attend a real-life Floralia, check this out.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

I love the idea that the painting made references to the Medici. It's like homemade memes with niche references that can only be understood within your friend group.

I love the way you walk us through the narrative of this painting! I've seen it so many times but honestly never knew the action that was happening in it. I feel like this is a plague of so much art that has become this well-known. You almost become blind to the details.