It’s likely that you’ve come across the French writer and politician, Victor Hugo (1802-1885). But if the name doesn’t ring a bell, his literary legacy – Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame – might.

In addition to literary giantism, Hugo was deeply embedded in political discourse of nineteenth-century France. He was outspoken on matters of state: he advocated for the abolition of slavery, he campaigned for the end of the death penalty, and he was outspoken against the emperor, Napoleon III, in favour of a French republic.

Hugo’s drawings are significantly less well-known than his novels and political writings. This is the focus of the Royal Academy’s current exhibition, Astonishing Things, which reveals the highly sensitive, spiritual, and introspective side to Hugo’s character. In spotlighting Hugo’s status as an artist (not his status as a man of letters), the exhibition raises a very interesting question: that is, what can a picture tell us that a text cannot, and vice versa?

The answer – a quotation from Hugo himself – is printed on the gallery walls. These things people insist on calling “my drawings”, he writes, were made in the margins or on the covers of manuscripts during hours of almost unconscious reverie with what remained of the ink in my pen.

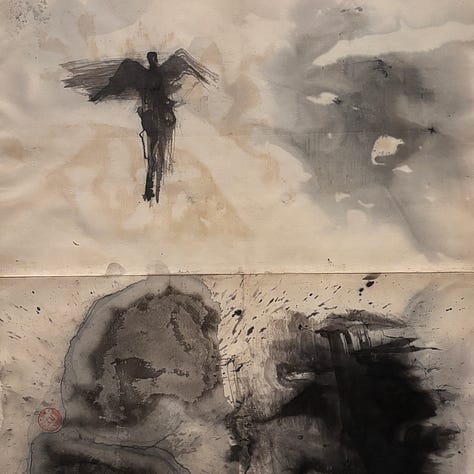

What this tells us is that the processes of drawing and writing for Hugo are deeply intertwined, but altogether distinct. Hugo drew as he wrote, using leftover ink for pictures which were not intended as illustrations but rather as part of a broader imaginative process. Made ‘in the margins’ or ‘on the covers’ of his manuscripts, these doodles signify Hugo’s working through of ideas – of settings, moods, characters, creatures, or even spirits – before articulating them in concrete sentences. Sometimes Hugo even lets the ideas work themselves out, allowing the ink to run free, experimenting with shadows and silhouettes. The whole process seems to have been intuitive and liberated, and very unlike Hugo’s vastly structured, narrative-driven novels.

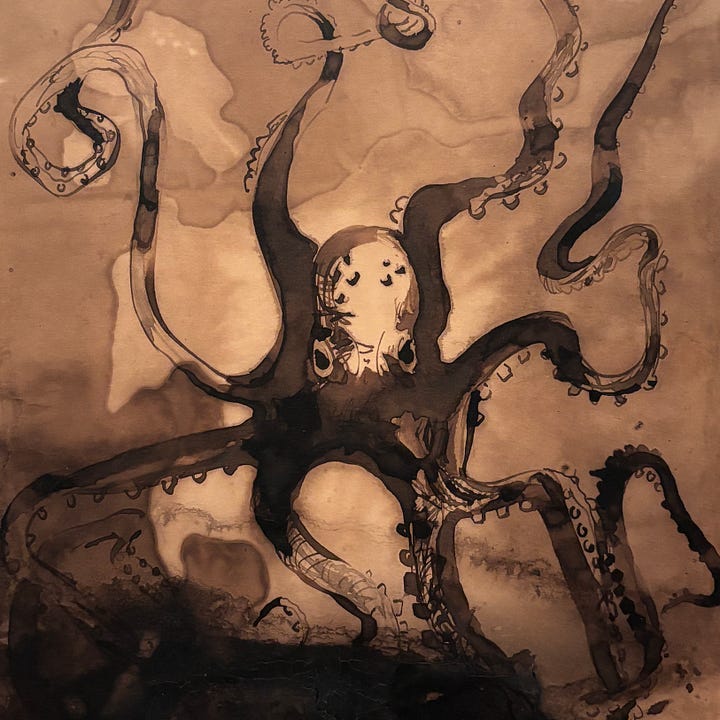

It is not insignificant that Hugo returns to the same motifs over and over again in his drawings. Ruins, dark fog, rugged boulders, winding staircases, ironmongery, waves and shipwrecks. There are otherworldly beasts and creepy-crawlies: spiders, octopi, serpents. Horribly disembodied arms and skulls. Mushrooms and flora, sprouting out of Gothic sculptures. All are cast in earthy tones of brown and black, meandering fluidly across sepia-tinted paper.

Hugo’s dark visions could easily be compared with Francisco Goya’s Pinturas Negras, which are similarly disturbing and widely believed to be reflective of the artist’s intense inner turmoil. They might also be read as narrative illustrations – as companion-pieces to his novels (such as The Toilers of the Sea, which is set on a bleak island) – akin to Henry Fuseli’s narrative illustrations of well-known horror stories like Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Dante’s Inferno.

However, I think there is a third, maybe more practical, way we can read Hugo’s drawings. They are, in large part, landscapes of the God-forsaken Channel Islands where Hugo was exiled for twenty years, from 1851 to 1870 (because of his opposition to Napoleon III).

The Channel Islands are a small archipelago off the coast of Normandy, France. They enjoy high humidity, frequent showers, strong Atlantic winds, and rugged coastlines. They’re small. They’re secluded. They are full of crumbling castles and fortifications, with a unique architectural character shaped by centuries of French and English military history. In other words: the Channel Islands – for all their foibles, their extreme weather and provinciality – offer the perfect source material for an artist of the Gothic persuasion.

So, here is your answer to the question ‘what can a picture tell us that a text cannot, and vice versa’: through Hugo’s ink drawings we can actually visualise the emotional and symbolic weight of exile, and through them experience the same sense of sublime wonder and spiritual desolation that permeated his life during those years. His novels give us plots, characters, and political arguments. But his drawings give us moods. They are not just emotive in theme, but also emotive in form: intuitive, elemental, and born from observation of the natural world. In Hugo’s pictures, we are not just reading about exile — we are seeing it, feeling it, and literally ‘weathering’ it.

And this brings me to the biggest presence in Hugo’s drawings: the ocean. Apparently Hugo was so obsessed with the ocean as a metaphor for the ever-changing creative process, for inspiration, and for the sublime that he was nicknamed ‘ocean man’ (or, at least, that he called himself that). When he was building his fabulously Gothic home, Hauteville House, on the island of Guernsey Hugo installed a lookout point on the top floor with views of the French coastline. It was from here that he would write:

Thoughtfully, I write at my window, I watch the flow being born, expiring, reborn, and the gulls cutting through the air. The ships in the wind open their wingspans and look in the distance like large figures strolling on the sea.

The ocean is everywhere in these drawings. Not only is it in the waves and their inhabitants – the serpent and the octopi – but it’s also in the medium. These are ink drawings, which means they’re water-based. The form of Hugo’s blots and washes reflect his subject: the mercurial, inscrutable, and merciless power of the sea.

What emerges from Astonishing Things is not only a deeper understanding of Hugo as a creative mind, but also a reminder that drawings and writings work differently.

Unlike Hugo’s novels, these small pictures hold ambiguity and meaning in equal measure. Look closely: an inkblot suddenly morphs into a human face. A dark mass becomes an open gate. Ghastly limbs arise from a stain. Flowers sprout from the ruins. His ‘taches’ (“accidental marks”), are entirely abstract, yet also full of emotion.

I never thought of Hugo as such a free, experimental, introspective kind of artist — or, even, really as an artist at all. This exhibition changed my perspective.

You can see it in London until June 2025.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper and my Tiktok @theculturedump, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Thank you for teaching me something new and wonderful today!! I had no idea that the author of such dense works as Les Mis created such fluid, emotive art. It’s a poignant demonstration of the inspirational and maddening nature of seclusion such as his exile.

These are wonderful! Thank you so much for sharing them, Rebecca - they are very much to my taste!