Why is the internet obsessed with this painting?

On the resurgence of Alexandre Cabanel's 'The Fallen Angel'

Alexandre Cabanel’s Fallen Angel is a dramatic, Romantic, erotic painting. It depicts the moment when the angel Lucifer (‘morning star’) has been cast out of Heaven. He is being punished for the sin of pride.

Cabanel’s Lucifer bears all the muscular power of a Classical statue, and yet, there’s also something about his pose which seems really vulnerable. He’s not nude: he is naked, and he’s trying to escape humiliation. As he turns away from us, a single tear falls from his bright blue eye. This tear is full of emotion. It portends a mixture of shame and fury, foreshadowing what is yet to come (Hell is about to break loose).

Until fairly recently, paintings like Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel (1847) had been out of fashion for a long time. A really long time. Like, at least since the end of the nineteenth century. But why, then, has this painting experienced a surprising resurgence among Gen Z through platforms like TikTok?

Some Important Historical Context

The Fallen Angel is exemplary of the type of art which was exhibited at the ‘Salon de Paris’ in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This Salon was the prestigious institution which set the standards for European visual culture at the time.

To properly understand The Fallen Angel, it’s important to first understand these standards. Everyone thought about art very differently in 1847 than they do today. Concepts like Cubism, Modernism, abstraction, installation, performance art, banana art (and really any form of fine art that wasn’t painting, sculpture, or architecture) were simply a glint in the far-flung future.

At the Salon, it was expected that painting should adhere to a strict set of rules. The governing rule was a ‘hierarchy of genres’, which prioritised illustrations of grand, epic narratives from Ancient mythology, the Bible, and history. Think, scenes from the Odyssey, from Genesis, from the New Testament, events from the Napoleonic Wars and, of course, Biblical stories like the Fall of Satan.

These paintings had to contain multiple human figures with idealised bodies and harmonious proportions — qualities which had long been associated with Classical and Renaissance art.

Most importantly, the Academic Salon paintings had to convey a moral message. Ideally, this message would reflect civic and religious ideals like heroism, martyrdom, virtue, and redemption. Sometimes (as with Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel), these paintings could reflect the consequences of straying from these ideals. This is why Cabanel’s Lucifer is so affecting.

However, by 1863, the Salon and its strict standards were falling out of favour. It all began with the Salon des Refusés, where rejects from the Salon (like Édouard Manet) began to challenge the authority of the establishment, paving the way for Modernism. Movements like Impressionism, led by Monet, Degas, and Renoir, broke the Academy’s rules entirely. They started painting scenes from daily life instead of grand, moral stories. They experimented with light and colour. They didn’t blend their brushstrokes. It was revolutionary, brilliant, and essential. And art has never been the same.

Monet is a household name. Who the heck is Cabanel?

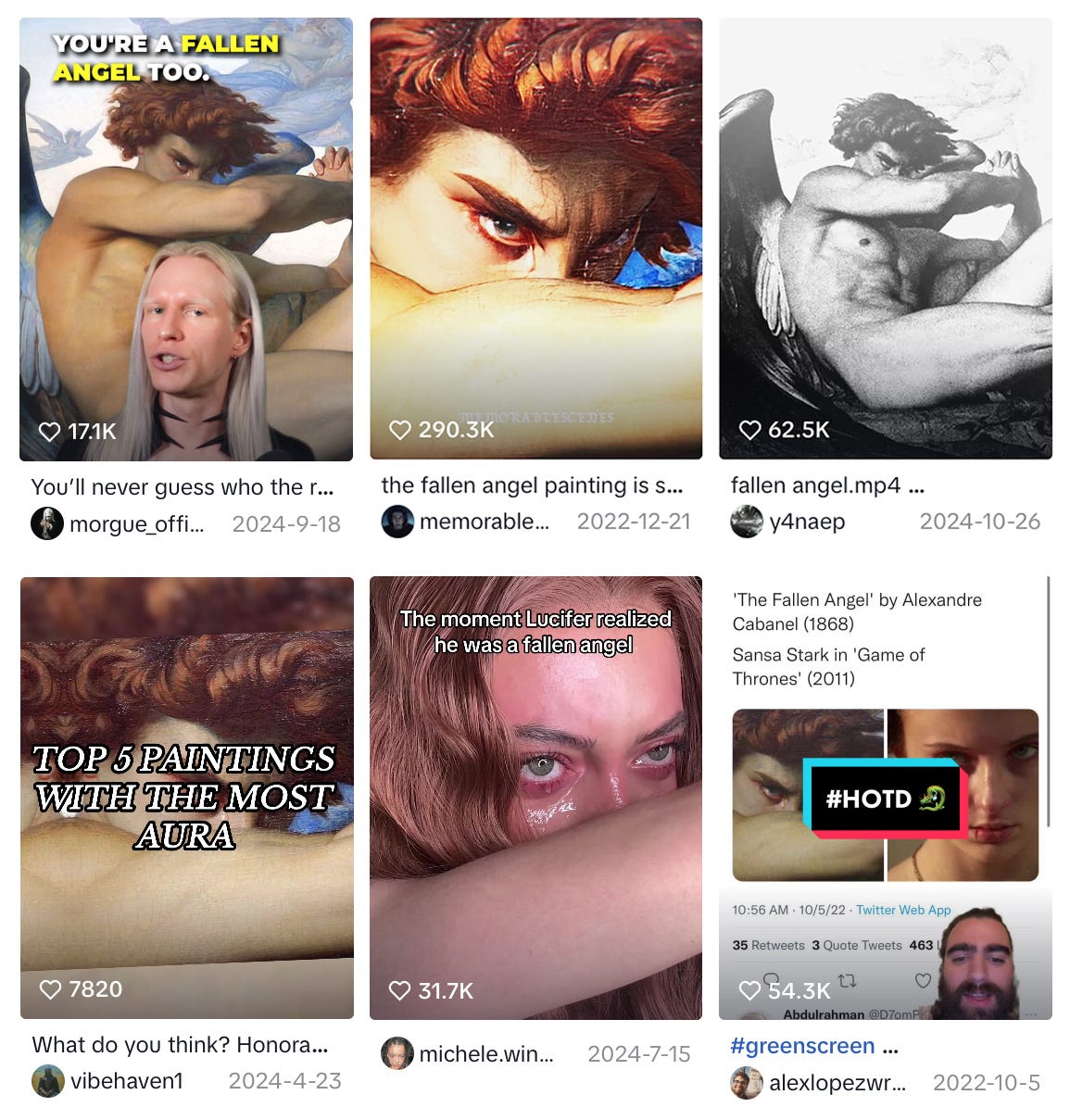

Cabanel’s Sudden Virality

This graph shows the trends in Google searches for Alexandre Cabanel’s Fallen Angel since 2004. Interestingly, it seems to have spiked around 2018-2022, and has stayed elevated since.

So, what happened in 2018? Why has Cabanel’s Fallen Angel been all over my social media feed? I seem unable to escape it.

The answer, I think, is a combination of intersecting factors — factors relating to technology, politics, to social and visual cultures — which created the perfect conditions for a painting of this kind to go viral.

The first point is that in August 2018, the popular app Musical.ly merged with TikTok, leading to TikTok's rapid growth. From this moment we began to see an explosion of a new kind of content on digital media: short-form videos. While this format had been around since the Vine days, it was not until the mainstreaming of Tiktok in 2018 that these bite-size verticals became the primary way that information was communicated online.

The significance of the short-form video for the dissemination of art, particularly historic, classical art, is quite interesting. Classical Art Memes had been around on Facebook since time immemorial; however, with the popularising of short-form came a new way to experience visual culture and, crucially (very crucially), for us to experience visual culture together. The medium was cinematic, so the content had to be too.

Enter the montage, and enter the dramatic edit. Enter the rapidly paced cycling video trends, such as the ‘Accidental Baroque’ and ‘No painting has ever affected me’. Enter art-history-adjacent ‘aesthetics’ like Dark Academia and old money. Enter the cosplayers and beauty influencers, enter tutorials on how to dress up as characters from Renaissance, Romantic, and Victorian paintings.

Enter a new, bizarrely conventional, Tiktok art-historical canon made up in the vast majority of nineteenth-century, European, male painters.

The… Tiktok Canon?

Pictured above are two viral videos on Tiktok. Both show influencers standing in front of famous artworks in the National Gallery and Tate Britain. The paintings are The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by Paul Delaroche and Ophelia (1851) by Sir John Everett Millais. There are many such videos. Other favourites are Auguste Toulmouche’s Reluctant Fiancée (1866), Ilya Repin’s Ivan the Terrible (1885), and Vasili Pukirev’s The Unequal Marriage (1862).

What is it about nineteenth-century paintings? Why is it never Monet or Picasso or Kandinsky or Rothko? The Harlem Renaissance? Basquiat? Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Yayoi Kusama?

Could it be that nineteenth-century paintings from traditions like the French and Russian Academies and the English Pre-Raphaelites tend to have clear, articulable, cinematic stories? Indeed, each of these paintings might be compared to shots from movies, TV shows, and video games (sometimes they’re quite intentionally referenced by movies, TV shows, and video games). I wonder whether these nineteenth-century paintings call on image-reading skills which the Tiktok generation are extremely proficient in.

And the most popular of these Tiktok-viral paintings is without doubt Cabanel’s Fallen Angel. Millions upon millions of views have been racked up on videos to do with this painting.

One of my followers suggested that the popularity of Cabanel’s Fallen Angel in recent years could be related to its features in contemporary legacy media. I agree with this, because there are a number of good examples. The main one, I think, is a shot of Anakin Skywalker in Star Wars: Episode III: Revenge of the Sith which clearly symbolises Anakin’s transition to the Dark Side of the Force. A more recent reference, however, comes in Netflix’s animated TV series Arcane (a breakout success of 2021). Zoomed into the main character’s eye, the frame signifies a fall from grace, and is a crucial – and rather evil – moment of character development for the protagonist.

This motif of the Satanic anti-hero was also especially prevalent in other TV series which became popular around 2018-22: including Lucifer (2020, 2022) and Good Omens (2019, 2023). This period saw a fan revival of the cancelled NBC show Hannibal (2015), which revels in Satanic imagery. A webcomic (now Amazon Prime series) set in Hell titled Hazbin Hotel (2019) has also bred countless fan responses to the tune of Cabanel’s Fallen Angel.

History Repeats Itself

But then, one wonders, why was The Fallen Angel as a subject so appealing to internet-based audiences in 2018-22? And, further to that, is there something about Cabanel’s painting in particular which made it the viral one? It’s certainly not the only depiction of the Fall of Lucifer on offer. Just Google ‘The Fall of the Rebel Angels’ and you’ll see what I mean (Pieter Bruegel, Beccafumi, Peter Paul Rubens, Gustave Doré…).

Could it be that, as the world grappled with crises in 2020 — crises of health, of technology, of identity — that Cabanel’s angsty, isolated Fallen Angel might have mirrored public sentiment? The pandemic certainly saw a rise in collective introspection: partially because of lockdown, partially because of global politics, but also partially because of larger, broader, and more fundamental changes in the way we interact (ie. entirely via computers). For the arts and humanities, social media became a so-called ‘third place’ — a much-needed social environment separate from home (first place) and work (second place).

Perhaps for these reasons, Cabanel’s painting was adopted, for better or for worse, by a disillusioned, destabilised, and doomscrolling audience, who were looking for common ground.

And who can blame them? If we look at other points in history where the motif of the Fallen Angel has become popular in art, we can see that these are always times of immense social upheaval.

Look back, for instance, to 1658 and 1664, when John Milton wrote Paradise Lost. Paradise Lost is an epic retelling of the Bible, and it contains a deeply complex portrayal of Satan. Milton’s Satan is charismatic and determined, with tragic heroic qualities that make for a compelling and alluring character. Although Satan is technically the antagonist in Paradise Lost, he’s more of an anti-hero.

Crucially, Milton wrote Paradise Lost just after the bitterly violent English Civil War (1642-51). In some ways, his sympathetic portrayal of Satan can be read as a reaction to this political turmoil, in support of revolutionary feeling.

Later, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Milton’s Satan became all the rage again in Romantic art and poetry. Why? Because of profound global unrest, because of rebellions in America, France, and Haiti, and because of bloody Napoleon, who was creating chaos everywhere.

Artists in this period were drawn to Milton’s Satan because of how he embodied many of the revolutionary ideas which were then in circulation. Remember: Satan has a bit of a problem with authority. He doesn’t back down. And he questions the status quo.

So, coming back to the modern day, of all the Academic paintings which might have gone viral, it doesn’t especially surprise me that Cabanel’s Fallen Angel is the chosen one. Because even though it is quite a traditional painting in a lot of ways, it also seemingly embodies a number of feelings — whether those be anger, frustration, shame, empowerment, or hope — which are already present in the culture.

What is more subversive, and more revolutionary, than reviving something which has been out of fashion for almost two hundred years?

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions in London.

Great painting, great analysis.

So Nailed it! First thought I had was politics and unrest. You took it all the way home. Interesting point about literal art and story telling. The alignment with the anime-manga generation is astute. Picking up the Good Omens affinity (I ended up bingeing it when I broke my foot this last year. Better than I anticipated but also because, if I am honest with myself, I thought we were out of this mess— quite the opposite) brings it to its macabre Beetlejuice climax. This is not over yet. We need the Blake of our next generation. This is most likely the kind of art that will encourage whom ever they may be.