You need to know about 'Flaming June'

Leighton's apricot-hued seductress is on loan until January 2025

Image: Lord Frederic Leighton, ‘Flaming June’, c. 1895.

I first saw Lord Leighton’s Flaming June in 2016, when it was displayed in his studio in Holland Park. Framed in sumptuous gold, bursting with rich flavour, Flaming June is one of the greatest masterpieces from the Pre-Raphaelite period. It’s actually one of my favourite paintings ever. So iconic is Leighton’s somnolent beauty that I’ve seen her tattooed on more than one occasion.

This is a picture that exudes power: not just in terms of its colour and light, but also in its unusual composition. For a painting so simple (effectively, a portrait), it really pushes the boundaries of perspective, anatomy, foreshortening. June’s spiralling pose (which, in combination with the setting, puts me in mind of a big orange seashell) absolutely has a hypnotic effect. It draws the viewer’s eye from the bottom-right of the painting. Entering here via a whorl of red fabric, we involuntarily slide around June’s body, beginning with her toes, moving past her beautifully-turned ankles, around her knees, thighs, and various contours (!) of her body, until we reach her rosy face.

If that doesn’t convince you to go see her, I don’t know what will.

Leighton’s painting is probably based on a destroyed painting by Michelangelo, Leda and the Swan. Although now lost, this mysterious fresco lives on through a number of drawings by Michelangelo’s followers (like Rosso Fiorentino), one of which is in the Royal Academy collections. Leighton, who was president of the Royal Academy from 1878 to 1896, would certainly have seen this copy. I was surprised to see that this was not included in the exhibit.

Images: (right) Rosso Fiorentino (?) after Michelangelo, ‘Leda and the Swan’, c. 15th century; (left), Michelangelo, ‘Night’, c. 1520.

June is definitely also related to Michelangelo’s statue, Night, from the Medici Chapel in Florence. Night is one of a series of allegorical figures (Night, Day, Dawn, and Dusk) which Michelangelo designed for the tombs Giuliano de' Medici and Lorenzo de' Medici. These sculptures symbolise the passage of time. Much like both the Leda and June, Night is also a heavy, languid, sleepy, muscular figure.

Leighton innovates on Michelangelo’s slumberous beauties quite effectively in June. She isn’t nearly as monumental or stony as they are. She is much softer, and less androgynous: squishier, frillier, and more alive — though she definitely possesses that same archetypal power.

So why is the painting named June? Well, a bit like Michelangelo’s Night, she’s a metaphor. June is quite literally a representation of the month of June! Leighton has sought to capture the feeling of a sleepy, warm, sanguine, summer afternoon… of the kind we never actually get in England. Perhaps this is one reason why there is a bouquet of exotic oleander flowers in the top right-hand corner of the composition. This suggests that June (like any sensible British tourist) has fled to Southern Europe or North Africa for her summer nap.

Shockingly, Leighton’s June was lost in the early 1900s. The painting was rediscovered during the refurbishment of a house in Battersea in the 1960s. It then made its way to an antiques shop on the Kings Road and, apocryphally, Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber tried to buy it, but was disallowed by his grandmother who would not loan him the asking price of £50.00. She said, ‘I will not have Victorian junk in my flat’. Thereafter, June was purchased at auction by the Museo de Arte de Ponce and enshrined in their collection in Puerto Rico.

Now June rarely makes her way home back to the shores of Blighty, and lives a cool eight thousand kilometres from her origin.

Luckily, she is on loan to the Royal Academy until January 2025, and admission is free!

The exhibition, curated by Dr. Hannah Higham, an expert in sculpture, is located in the Collection Gallery, opposite the Main Galleries, and is therefore almost totally deserted. When I went to see Flaming June, I was basically the only person in the room. You could not have a better opportunity to spend some personal time with Leighton’s salmon goddess.

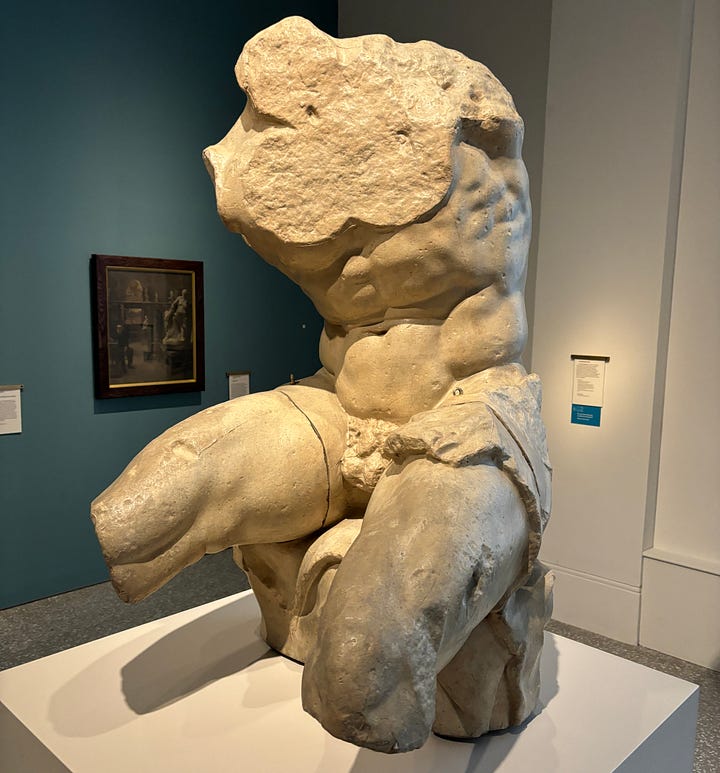

Dr. Higham has really leaned into the importance of the influence of Michelangelo, sculpture, and antiquity on Leighton’s praxis as a painter. She has positioned Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo directly opposite June, and furnished the gallery with plaster casts of the ancient Belvedere Torso and Laocoön statues — both of which greatly influenced Michelangelo and Leighton.

Images: (right) Appollonius, ‘Belvedere Torso’, 1st century copy; (left) Michelangelo, ‘Taddei Tondo’, c. 1504-05

There are some real big-hitters in this exhibit. A copy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper adorns the left-hand wall; Sir James Thornhill’s studies of Raphael’s cartoons are shown on the right. Although you would think that these huge, grandiose, historical paintings might dwarf Flaming June, the effect is quite the opposite. In fact: Leighton’s June is sufficiently powerful not to need any entourage at all, and her bright aura shines out across the exhibit, managing to make even Michelangelo and Raphael look, well, a bit boring!

Image: Sir James Thornhill after Raphael, ‘Acts of the Apostles’, c. 1729-31

Images: (right) Sir Joshua Reynolds, ‘Self Portrait’ c. 1780; (left) Sir Benjamin West, ‘Self-Portrait’ c. 1793.*

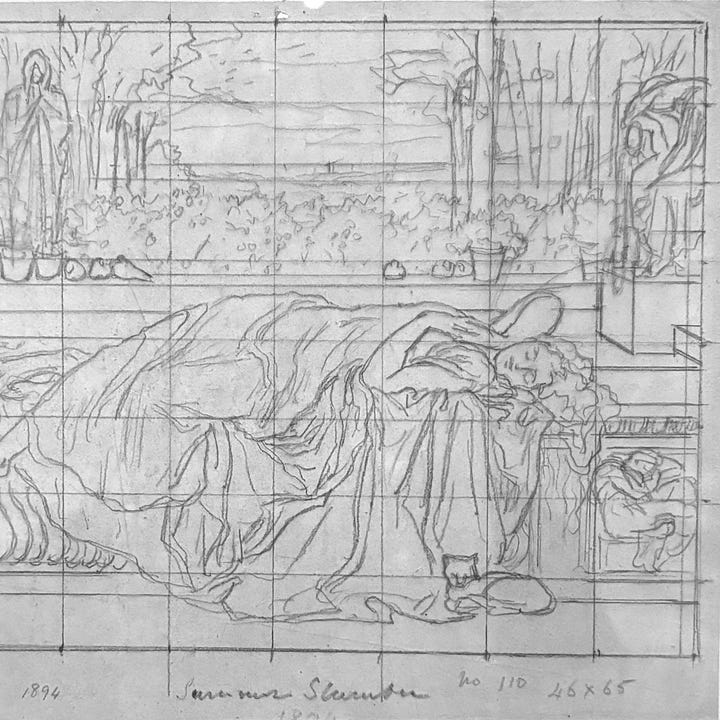

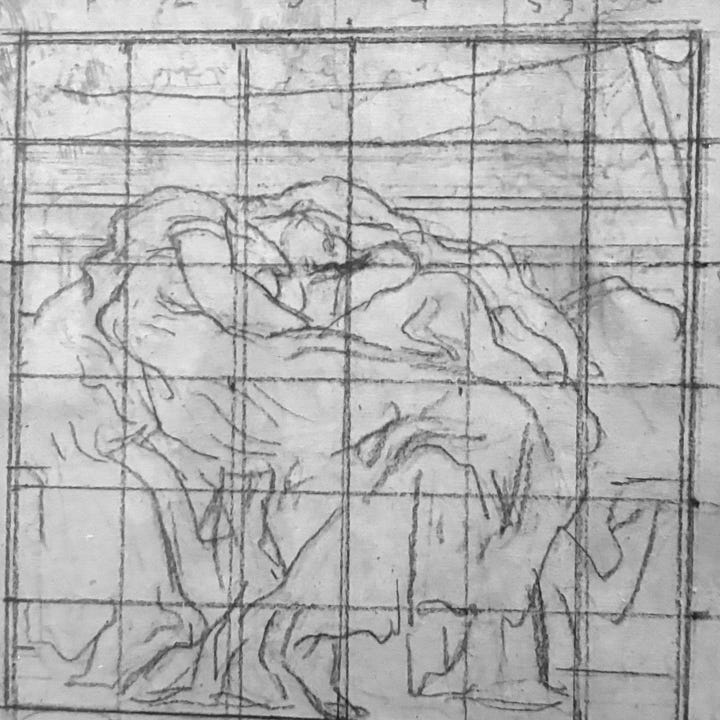

Higham’s show is a crucible of some of the highest-status works the Royal Academy has to offer: Michelangelo, Raphael, Da Vinci, and its inaugural presidents, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Sir Benjamin West. However, I truly do think that the most wonderful objects in this exhibition, other than June, of course, are Leighton’s preparatory sketches. I had no idea that he really did a lot of these, trying to get June exactly right. My favourite is a tiny thumbnail in the very bottom-right of a larger composition named Summer Slumber. It shows how the most magnificent ideas can come from the smallest of doodles.

Image: Leighton, squared up tracing for ‘Summer Slumber’ (right), and ‘Flaming June’ (left) c. 1894.

Fin.

*Note how Reynolds portrays himself leaning on a bust of Michelangelo, and West shows a cast of the Belvedere Torso behind his desk. What does this say about how they are trying to present themselves?

I loved visiting Flaming June recently too. Such a stunning painting.

And many of the other works in that room with her are actually part of the permanent display in the Royal Academy (The Michelangelo Tondo in particular is one of my favourite works in London - I visit it regularly!)

But I actually really like how you picked up on the curation side of things here too, and how these kinds of works would no doubt have influenced Leighton's painting.

Really great stuff. I think you're going to do very well with this newsletter on here!

I’ll put this on my list to go and see, thanks