Nightmarish Paintings for Halloween

The scariest artist you've never heard of: Antoine Joseph Weirtz (1806 - 1865)

Dismemberment, infanticide, severed heads, and live burial: these are the themes we’re going to be talking about today, in that order. Just in time for spooky season.

The painter Antoine Joseph Wiertz was born in Belgium in 1806. He came from a modest background, and from an early age he showed ambitions to become a great artist. He enrolled at the Antwerp art academy in 1820 (when he was only 14), where his precocious talents won him funding from the Belgian state. Several years later, Wiertz moved to Paris to study at the Louvre. There, he developed a preference for old masters — like Michelangelo and Rubens — over contemporary French painters like Girodet. Wiertz would continually emulate old master compositions and techniques throughout his career.

You probably haven’t heard of Wiertz because this negative critical response followed him all throughout his life.

There is a museum in Belgium that is dedicated to Wiertz; however, on the whole, he is only really known to specialists. He generally considered a fringe eccentric, an exemplar of wasted potential, and as an early prefiguration of the dark, ethereal Belgian symbolist movement of the 1890s to 1910s.

Wiertz’s paintings are, to put it plainly, very unsettling. Perhaps this is because he is ‘obsessed by extremes, not only of scale but frequently, too, of emotion’. Some of his works are chaotic and melodramatic, while others are hauntingly quiet and meticulously detailed. He did not like the glossy finish of traditional oil painting, and developed a method that combined the smooth blending of oil paints with the muted finish of watercolours. This is what gives Wiertz’s later compositions an uncannily smooth, almost unnatural glow. Disturbingly, it is possible that the chemicals Wiertz used in this process may have contributed to his premature death at age 59.

For the spooky season, I’ve curated a list of four of his most creepy, unnerving works. Proceed with caution.

4. The Greeks and the Trojans Fighting over the Body of Patroclus (c. 1836)

Like any nineteenth-century painter worth his salt, Wiertz studied in Rome for a short period to study the Classics and Renaissance. During this sojourn, in 1836, he painted his first large-scale history, The Greeks and Trojans Fighting over the Body of Patroclus, before moving back to Belgium the following year. This painting would later be exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1839, where it was widely panned by critics, including the French writer Charles Baudelaire who called Wiertz ‘a charlatan, idiot, thief … who does not know how to draw and whose stupidity is as massive as his giants’.

The first thing you have to know about this painting is that it is incredibly large! It is 26 feet long. The enlarged, muscular bodies, and the dynamic, diagonal thrust of the composition are quintessentially Michelangelesque. The likeness between Patroclus’ expression and that of Henry Fuseli’s Satan, engraved by William Blake in 1790, is perhaps indicative of Weirtz’s similarities to earlier Gothic artists.

However, something about Wiertz’ painting is also really off. It is brutally violent, capturing the moment when the hero is literally torn limb from limb by the opposing forces of war.

The assailants are intensely crowded, entangled, and overlapping: disordered, speckled with bright-red hues, and their faces and bodies are pulsating with the energy of berserker rage. You can see Patroclus’ body — which is eerily peaceful compared to the mob around him — just beginning to tear from the pressure. The thin sliver of blood trickling from his belly indicates that his torso, like his toga, is about to rip. His arms are also frighteningly akimbo — are they dislocated?

3. Hunger, Madness, Crime (c. 1853)

The melodramatic horror in this image is self-evident. The woman’s crazed expression, the bloody knife, the dead child’s foot in the stove pot... you get the idea.

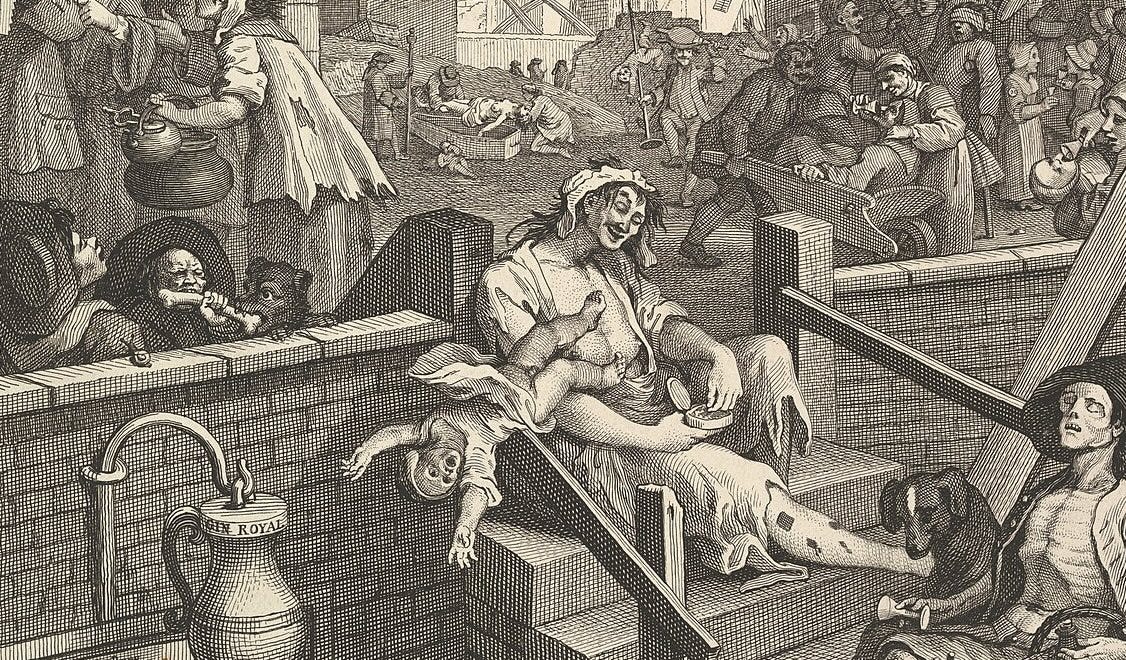

The central figure, abject and demented, is surrounded by food scraps, broken furniture, and newspapers. Why? Well, a bit like William Hogarth’s Gin Lane this terrifying scene of infanticide is a social commentary. It is a response to the rapid industrialisation of the nineteenth century, and the widespread poverty and disease which it incurred among the labouring workforce.

By 1850 Belgium had seen huge growth in urban areas owing to its booming coal, iron, and textile industries. However, with this growth came terrible suffering: overcrowding, no sanitation, and terrible working conditions. The figure in Wiertz’s horrifying painting symbolises these consequences. She has been driven first to hunger, then to insanity… and thereafter probably to something worse… cannibalism. It’s a cruel portrayal of the dehumanising effects of poverty.

There are a number of reasons why Wiertz’s painting is so much scarier than Hogarth’s Gin Lane (which, although serious in subject-matter, has a much lighter tone). One component is the claustrophobic framing of the space. Another is the strange, soft, highly saturated colours and stage lighting. These qualities only add to the sense of horror (just as colourful lighting effects do in slasher movies). In terms of imagery, one wonders whether this perverted echo of the archetype of mother and child is a sickening subversion of the holy family. Top-tier horror!

2. Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head (c. 1853)

Wiertz was clearly preoccupied with the dark side of life, and spent a lot of time considering whether or not it was possible for the human brain to continue thinking after it was severed from the body. So (like any sane person) he made a plan to go to a public execution, hypnotise himself, and attempt to enter into the mind of the unfortunate decapitate, to test this theory.

Weirtz recorded his experience as a severed head in a trio of paintings from 1853. A description which he writes alongside these in his notebook is exactly what you would imagine: ‘The guillotined head sees his coffin,’ so Weirtz writes, he ‘sees his trunk and limbs collapse, ready to be enclosed in the wooden box in which thousands of worms are about to devour his flesh’… and so on and so forth.

Unlike the previous works in this list, Weritz’s Visions of a Severed Head are not finished paintings. Rather, they are experimental, immediate, abstract responses to a bizarre spiritual experience. Nor, in my opinion, are they as outrightly scary as Patroclus and Hunger… however, there’s a dreamlike quality here which gets under the skin. The ghostly outlines of the clamouring voyeurs, the dismembered body, the abstract and frenetic application of paint... are these a bit like Goya’s Black Paintings?

1. The Premature Burial (c. 1854)

Coffins, cholera, and cadavers, this painting has it all. While live burial was not all that common in the nineteenth century (though probably more common than it is now), anxieties about it were widespread. Just read Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Premature Burial (1844).

One of the reasons for this was the spread of highly contagious diseases like cholera and plague in this period. These were mostly a consequence of the poor living conditions created by industrialisation and, in the case of fatality, they required swift burial to staunch the infection rate. The urgency of these burials, combined with the limited understanding of disease transmission, sometimes led to premature burials, as the focus was on quickly disposing of potentially infectious bodies.

This painting preys on very primal and rational fears of suffocation, confinement, disease, and darkness. Not only does it trigger visceral horror — for instance, in the terrified (and terrifying) look on the victim’s face; the dark, dank cellar; the scattered human remains, etc. — but it also explores the psychology of claustrophobia. The woman’s desperate expression, her frantic attempts to escape, and the eerie calmness of the scene combine to create a profoundly disturbing work of art that lingers in the viewer’s mind, forcing them to think about death and confinement.

Happy Halloween! 🎃

Fin.

I love these artists who weren't afraid to be weird and off-putting! 😅

Thanks for the nightmares!