Is Vincent Van Gogh a Poet or a Lover?

The National Gallery's new exhibition refreshingly highlights Van Gogh's method, not his madness

The National Gallery is 200 years old this year. It’s also been exactly 100 years since the Gallery acquired two of Vincent Van Gogh’s most famous paintings: Sunflowers and The Chair. To celebrate both of these anniversaries, they’re putting on a landmark exhibition. This show will run from now until the 19th of January 2025, and it’s expected to be very popular, so make sure to book your tickets in advance!

Van Gogh’s reputation precedes him. Few artists have had feature-length cinematic adaptations (or ‘Dr Who’ episodes) about their life and works. He has not one but two paintings in the Animal Crossing museum, which is a high accolade indeed. The legend of his total failure as an artist (Van Gogh never sold a painting in his life), combined with his posthumous success, offers a tragic, mythologised parable of immortal genius.

In 1889, after an argument with the painter Paul Gauguin, Van Gogh sliced off his earlobe. Van Gogh then checked into a mental health hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he stayed for several months. After a final frenzy of artistic activity between May and July 1890, he committed suicide in a field in Auvers-sur-Oise.

This story is one which numerous Van Gogh exhibitions have sought to tell. The ‘Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise’ exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay earlier this year, for instance, focused on his final paintings. Tumultuous, intense, and brimming with vibrant but frenetic energy: this was a show about a painter haunted by his own brilliance.

Curating Van Gogh’s works in a new way is actually very difficult to do. I’m pleased to say that the National Gallery has done this with flair and aplomb, offering something quite different from what I saw at the Musée d'Orsay.

Where Poets and Lovers really shines is in its reframing of how one might think about Van Gogh. It proves that he’s not an inspired lunatic but rather a careful and intentional artisan. Van Gogh, as this exhibition shows, was well-informed, exacting, and ambitious in his pursuit of mastery. Perhaps it is this, and not his madness, which is the true root of his popularity?

This show at the National Gallery contains 61 objects (some paintings, some drawings— drawings are unusual for Van Gogh), and I cannot cover them all here. I’m simply going to highlight the ones which tell the curatorial narrative…

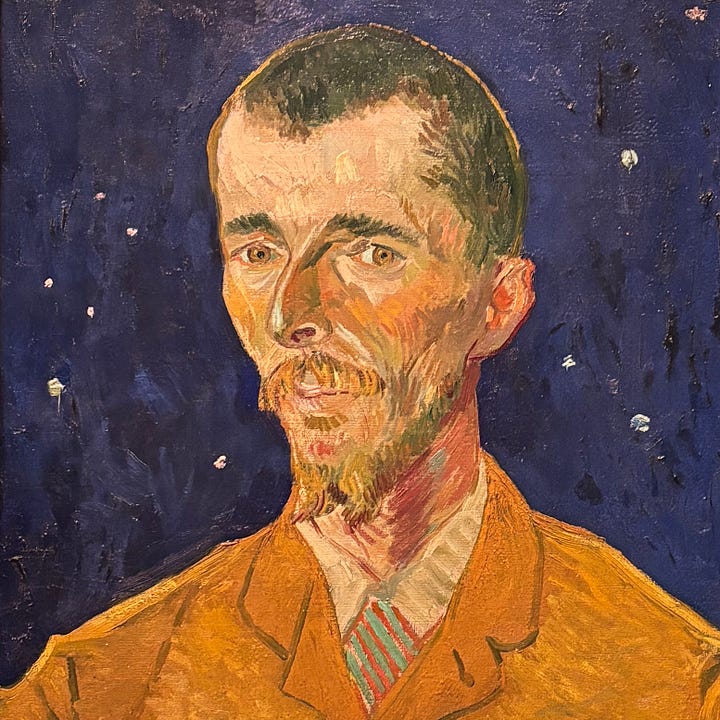

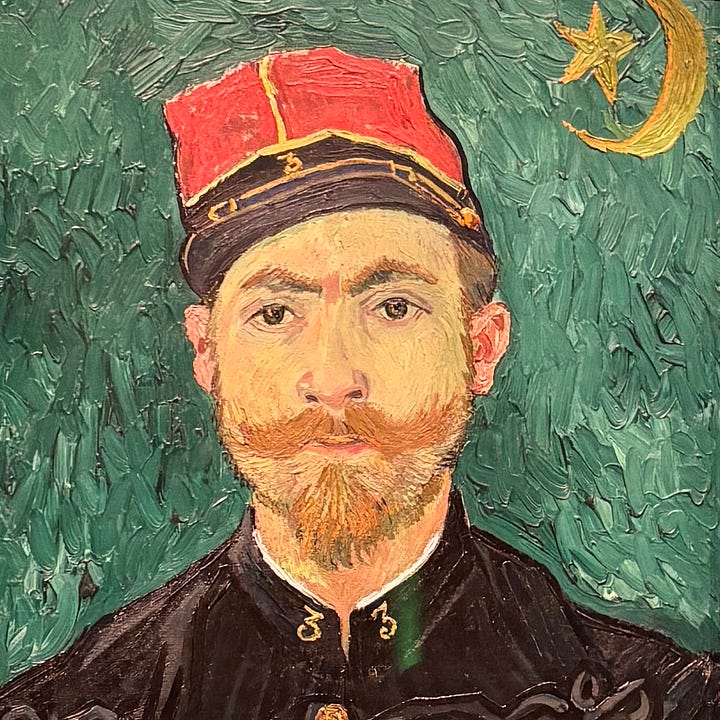

The Poet and The Lover, c.1888

So, why is the show called Poets and Lovers? Well, the question is answered in the first room. We are greeted by three pictures: two portraits and one plein air. The portraits are of Van Gogh’s friends, Eugène Boch (the Poet) and Lieutenant Milliet (the Lover). The landscape is the public garden just opposite Van Gogh’s ‘Yellow House’ in Arles, where much of this exhibition takes place.

These works represent the start of a new period for Van Gogh. Having just moved from Paris to the South of France in 1888, he has started to transform the quaint provincial landscape and its residents into universal archetypes.

The Poet and The Lover are two such archetypes. These paintings are companion pieces. Their compositions are similar, but their palettes are distinct: one is blue and orange; the other, red and green. Complimentary colours.

The Poet, Eugène Boch, represents the contemplative life. Like Van Gogh, Boch was a painter. His narrow face apparently reminded Van Gogh of the Italian poet Dante. In a letter to his brother Theo, Van Gogh describes his approach to the composition and colouring in this portrait: ‘I exaggerate the blond of the hair, I come to orange tones, chromes, pale lemon. Behind the head—instead of painting the dull wall of the mean room, I paint the infinite.’ The blue, starry background symbolises an expansive poetic mind.

The Lover instead signifies the active life. Lieutenant Milliet was an army man (his regimental emblem is in the top right-hand corner of the portrait), as well as a bit of a Casanova. Van Gogh apparently envied Milliet’s romantic escapades. This is why he playfully named Milliet, ‘The Lover’.

Sunflowers, c. 1888

This is the best of four Sunflower paintings that Van Gogh made between 1888 and 1889. It is a prize of the National Gallery collection and possibly one of the most well-known paintings in Western art.

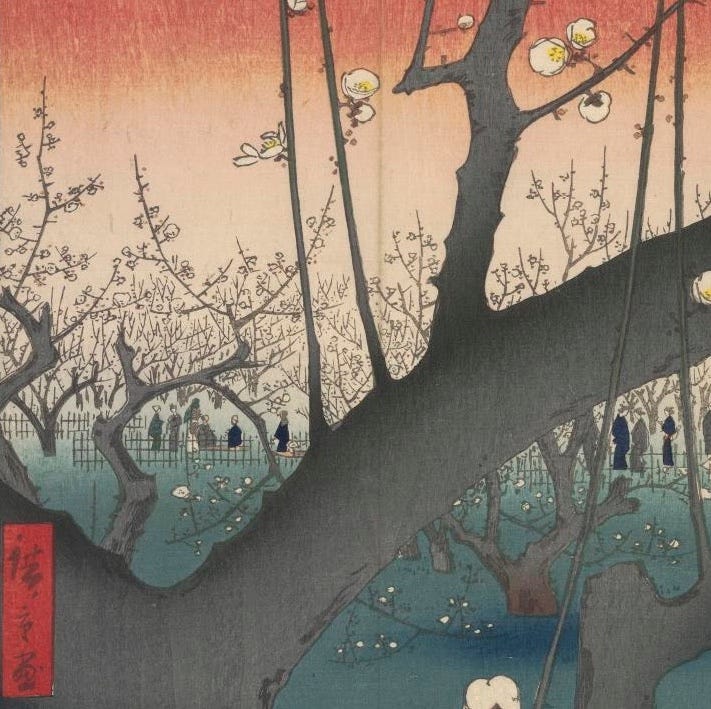

It’s profoundly influenced by the style of Japanese woodblock prints, which Van Gogh famously collected — we see this in the painting’s lack of shadows and clear, bright planes of colour.

However, there’s also a more traditional Dutch presence in the Sunflowers too. Looking closely, you’ll see that all of the sunflowers are at different stages of life: some are budding, others blooming, others wilting. In this, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers evokes the seventeenth-century Dutch genre of Vanitas painting. This is a type of Protestant religious art, often centred around natural objects like flowers and food, that serves as a reminder of the passage of time and the inevitability of death.

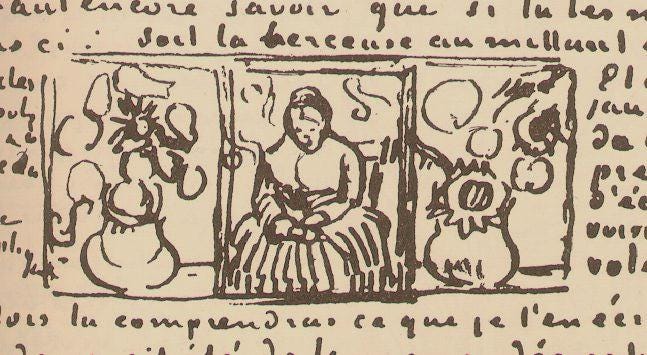

This exhibition also points out that Van Gogh had originally planned to exhibit these Sunflowers as part of a triptych. In a letter to his brother, Van Gogh explained how he originally wanted to display the Sunflowers alongside a portrait entitled La Berceuse (The Lullaby) and a second Sunflowers painting. He had intended for this to be a kind of modern, rural, reimagining of the Virgin Mary.

This National Gallery exhibition is the first to showcase these three paintings in this order, as Van Gogh had imagined!

The Sower, c. 1888

Van Gogh apparently believed that this painting, The Sower, was one of the most important works he produced during his time in Arles. It’s a tribute to an earlier French painting of the same name by Jean-François Millet (1850), who was known for his realistic portrayals of rural French life.

Like the Sunflowers, Van Gogh’s Sower fuses different elements from both the Eastern and Western schools. His bold, centralised, graphic motif of the tree invokes Andō Hiroshige’s Plum Garden at Kameido (c. 1857). This was a Japanese print which Van Gogh closely studied.

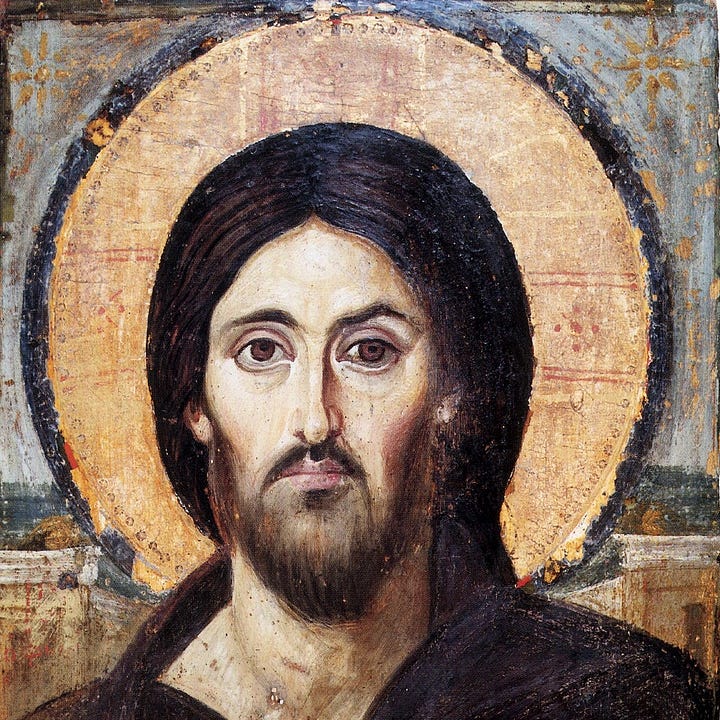

The bright, gold sun behind Van Gogh’s figure of the sower, however, also echoes the halo effects that we see in traditional Christian iconography. The act of ‘sowing’, too, has Christian overtones, being a Biblical metaphor for spreading the word of God.

More than simply an unflinching illustration of peasant life, then, Van Gogh’s Sower is actually erudite, spiritual, and intentional.

Oleanders, c. 1888

On the surface, Oleanders appears to be a straightforward still life — a simple composition of exotic flowers beside a stack of books. Yet, Van Gogh's work is imbued with layers of symbolism.

The oleander, a flower common in the South of France, serves as a geographical and temporal marker of Van Gogh's environment. Symbolically, its hardy nature often signifies eternal love, as it flourishes even in harsh conditions — an apt metaphor for beauty emerging from a barren landscape. However, the oleander is also notoriously poisonous, which adds complexity to its seemingly positive symbolism.

In this painting, Van Gogh seems to draw upon this darker undertone. The book prominently displayed is Émile Zola's La Joie de Vivre (1884), a novel that offers an unflinching examination of human suffering.

Through these elements, Van Gogh not only reveals his literary and poetic sensibilities but also highlights the thoughtful, deliberate nature of his creative process.

—

The exhibition ultimately highlights Van Gogh’s dual identity as both a poet and a lover. He’s a poet in his invocation of literary influences (like Dante and Zola) and in the careful control of his compositions. Quotations from his writings to friends and family are scattered across the walls, projecting an image of a man of letters (you can read Van Gogh’s letters here).

One room here is dedicated to Van Gogh’s Montmajor drawings. These ink compositions show just how carefully Van Gogh planned every line, demonstrating his ability to synthesise vast, expansive landscapes into intricate patterns and rhythms.

But what makes Van Gogh a ‘lover’? He never married, nor found success in casual relationships like his friend Lieutenant Milliet. The show implies that his greatest love was for his artistic vision. We see this in the letters to Theo, which brim with excitement about the future of painting: ‘The painter of the future,’ Vincent writes, ‘is a colourist such as there hasn’t been before’. ‘As long as autumn lasts I won’t have enough hands, canvas, or colours to paint the beautiful things that I see’.

While our viewing of this exhibition is inevitably coloured by the knowledge of what comes at the end of Van Gogh’s life, it also freshly imagines the man behind the myth. It shows us one who was motivated by learning and mastery, who tended his personal relationships, and who was also constantly thinking beyond the canvas in front of him.

Fin.

I’ve been to the National Gallery and we stumbled into the Van Gogh exhibit literally by accident; it was a magical moment to realize where I’d found myself. I have a photo in front of the sunflower painting. I absolutely love it. Van Gogh was unique and his life so very tragic. Great article.

I’ve been traveling the last months and miss all the art and exhibitions in London. This made me feel like I was right there in the gallery! Plus the back story and additional context on the Sower was such a surprise! I have so much more interest in that piece now. Thank you Rebecca.