Lord Leighton's Leisure-scapes

The unseen, intimate landscape portraits on offer at Leighton House

You may remember an article I wrote a few months back about Flaming June. One of my favourite paintings – fluffy, orange, and erotic – she’s been on display at the Royal Academy in London since February 2024. To celebrate, throughout September I spotlighted her creator, the artist Lord Frederic Leighton. I focused on his famous Academic paintings.

Leighton was the head of the Royal Academy from 1878 to 1896. His works are illustriously large, figurative, and epic. They are often characterised by grand, sexy, mythological narratives like The Bath of Psyche and The Garden of the Hesperides. Sometimes, they reflect Biblical stories or Renaissance ideals. Occasionally, they’re just portraits. He also made figure sculptures, clearly inspired by a lifelong study of Michelangelo.

Leighton, however, is not usually known as a landscape painter. Sure, there are sumptuous, rolling, dramatic landscape backgrounds in his works (as in Greek Girls Picking up Pebbles by the Sea) – but they’re never the focus of the image.

Right now, though, there’s an exhibition at Leighton House (Holland Park, London) which subverts this narrative. It’s called Leighton and Landscape, and it offers an entirely new take on Leighton as a painter.

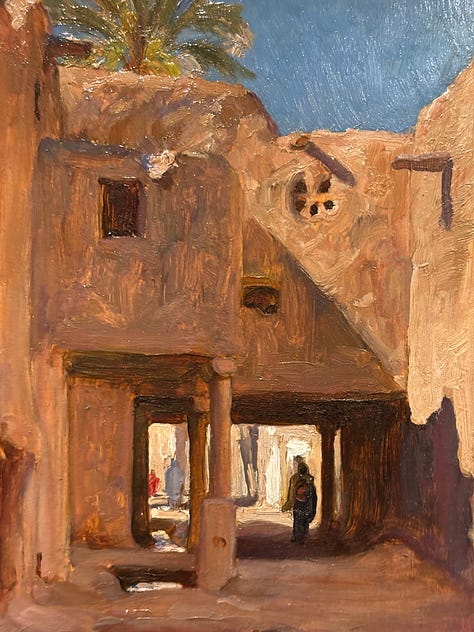

This show focuses purely on the small, personal, scenic paintings Leighton painted for his own pleasure. No frilly semi-nudes in sight – instead, the landscapes of Algeria, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Syria, Morocco are the subject of this exhibition.

‘Perhaps the artistic feeling for which Leighton has had least credit,’ wrote an insightful journalist in 1897, ‘which in him was exquisite, is the feeling for the landscape’. Another reviewer noted that Leighton’s landscapes ‘have the advantage of simplicity and directness’ (London Evening Standard, 15 April 1881). And it’s true: unlike the big paintings we usually associate with Leighton, these sketches were never meant for public display. They’re all about feeling – a simple, beautifully accomplished artistic response to nature. They’re almost like holiday photographs. Leighton called them ‘little notes of truth’.

Because of this personal quality, these landscapes are rather non-traditional. They’re not all painted in classic ‘landscape’ format. Many are tall, upright portraits, or zoomed-in studies of rock formations and architecture. They’re playful, often focusing on the interplay between man-made buildings and the natural world.

One of the inspirations for this exhibition was the recent acquisition of Leighton’s The Bay of Cadiz, Moonlight, painted during his first tour of Spain in 1866. It’s a sensitive night-time scene – quite ahead of its time – focused on light effects on water, colour, and shade. It feels reminiscent of some of Monet’s waterscapes, like those recently exhibited at the Courtauld.

Although these sketches were a welcome release from the highly detailed paintings Leighton usually presented at the Royal Academy, they weren’t entirely separate from his larger works. Sometimes, echoes of these landscapes turn up in the backgrounds of grander pieces – like in The Knucklebone Player, where the mountains of Rhonda, Puerto del Viento (painted in 1866), form the backdrop.

Leighton, much like the subject of his final painting Clytie (the Greek figure who falls in love with Apollo, the sun god), seems to have been a bit of a sun-worshipper. His landscapes from the Mediterranean and North Africa are noticeably more polished than those from, say, Scotland. Maybe it was the weather – his Highland landscapes feel a bit more hurried, whereas his work from sunnier climates is vibrant and rich.

But the 1860s seem to have been the golden years for Leighton’s landscape paintings, especially during his trip to the Nile in Egypt. He recorded the journey beautifully in a travel journal – just as much a wordsmith as a painter. ‘The earth was in colour like a lion’s skin,’ he wrote, ‘the sky of tremulous violet, fading in the zenith to a mysterious sapphire tint’. Beautiful.

Ultimately, Leighton and Landscape reveals a tender and unguarded side of Lord Leighton – one not often associated with the grandeur of his public works. These personal landscapes offer a glimpse into the quieter moments of his artistic life, suggesting that the emotional resonance of works like Flaming June owes as much to his travels and love of nature as it does to myth and legend. This exhibition reminds us that Leighton contains multitudes. He’s not just ‘Lord Leighton, PRA’; but also Frederick, the wandering landscape artist.

Thanks for reading! Check out my Instagram at @culture_dumper, where I post daily updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions in London.

That looks like an interesting exhibition! Thank you for sharing this!

I visited Flaming June (Ada Pullen) at the RA and saw her at Leighton house a few years ago when she came back for a visit. It was so inspiring to see the painting in Leighton's studio where she was painted. A beautiful picture. There is also a small sculpture at Leighton house of her younger sister Lena Pullen.