Reading Around the Renaissance

Four more must-reads for art lovers: Italian Renaissance edition

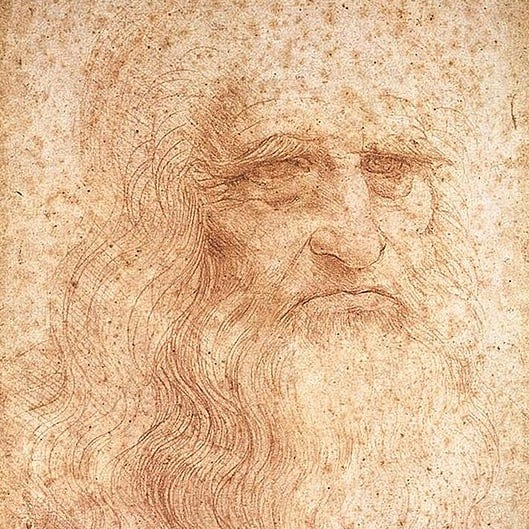

Next month, London’s Royal Academy is going to open a high-stakes exhibition on three Renaissance giants: Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Raphael. So entrenched are these names in our cultural memory, so endemic to our understanding of painting and sculpture, and so utterly fundamental in the fashioning of the arts — you definitely don’t need to have studied art history to know who these guys are!

Maybe because of this upcoming show at the RA, and maybe also because of their ongoing Flaming June exhibition (which involves a lot of Renaissance references) the sixteenth-century Italians have been on my mind recently… andiamo!

Following the success of my previous reading list, I’ve decided to create a series of articles called ‘Must-Reads for Art Lovers’. These will be my top picks for reading around different periods and themes in art history, all informed by The Culture Dump reader suggestions, personal favourites, and canonical classics.

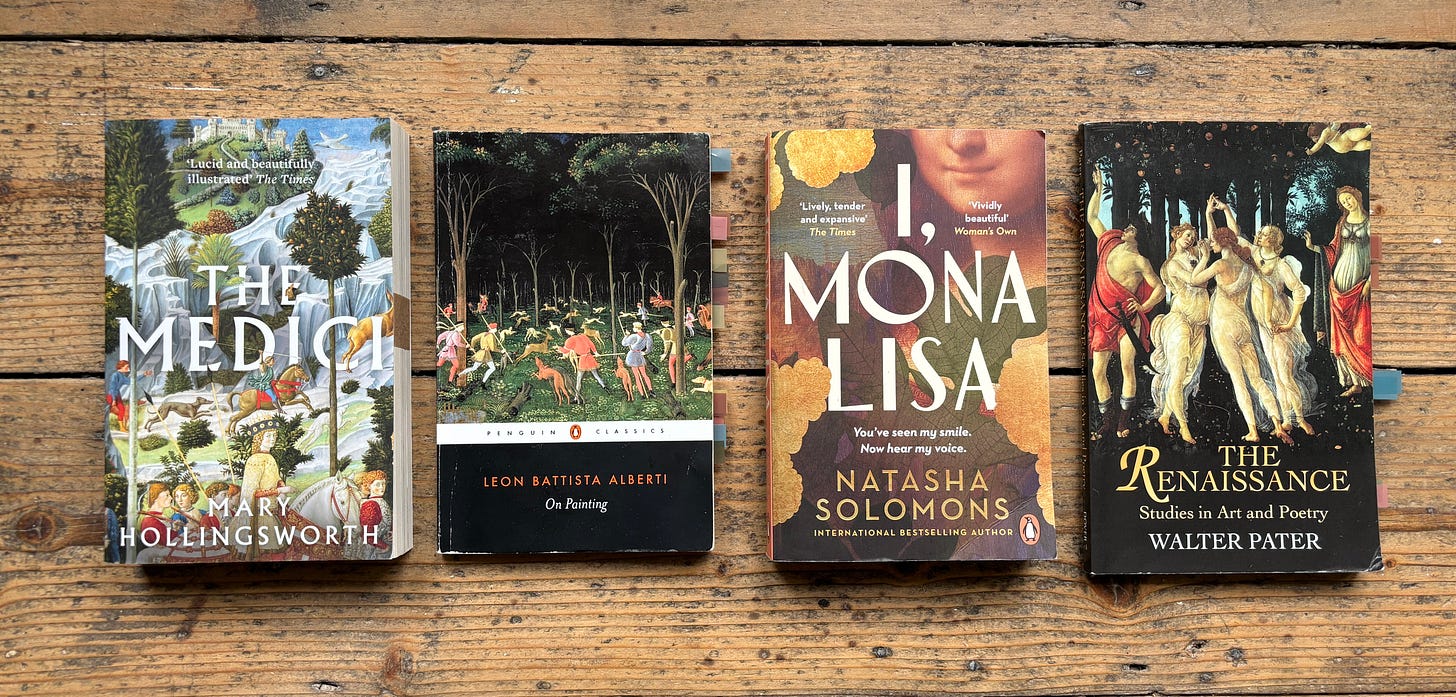

This week’s shortlist features four very different kinds of books about the Italian Renaissance. I’m hoping there is something here for everyone – from the casual reader of fiction to the connoisseur of critical theory.

This list isn’t meant to be remotely exhaustive (you'll notice Giorgio Vasari, often seen as the father of Renaissance art writing, isn’t here). Instead, it’s one that I hope sparks interest and discussion.

For the Humanists: Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting (1435)

Published in 1435, Alberti’s On Painting is definitely the oldest on this list. However, this does not mean it’s unreadable: in fact, it’s very short (only 100 pages), eminently clear, and many of its points about art still ring true today.

Groundbreaking and unprecedented, On Painting is the earliest known book dedicated entirely to the intellectual foundations of painting. It is probably responsible for the birth of art-critical analysis. It’s also a quintessential work of Renaissance Humanism, meaning that it draws on Classical art and philosophy as a foundation (Renaissance) and it also presents a belief in the value of human creativity and intellectual potential (Humanism).

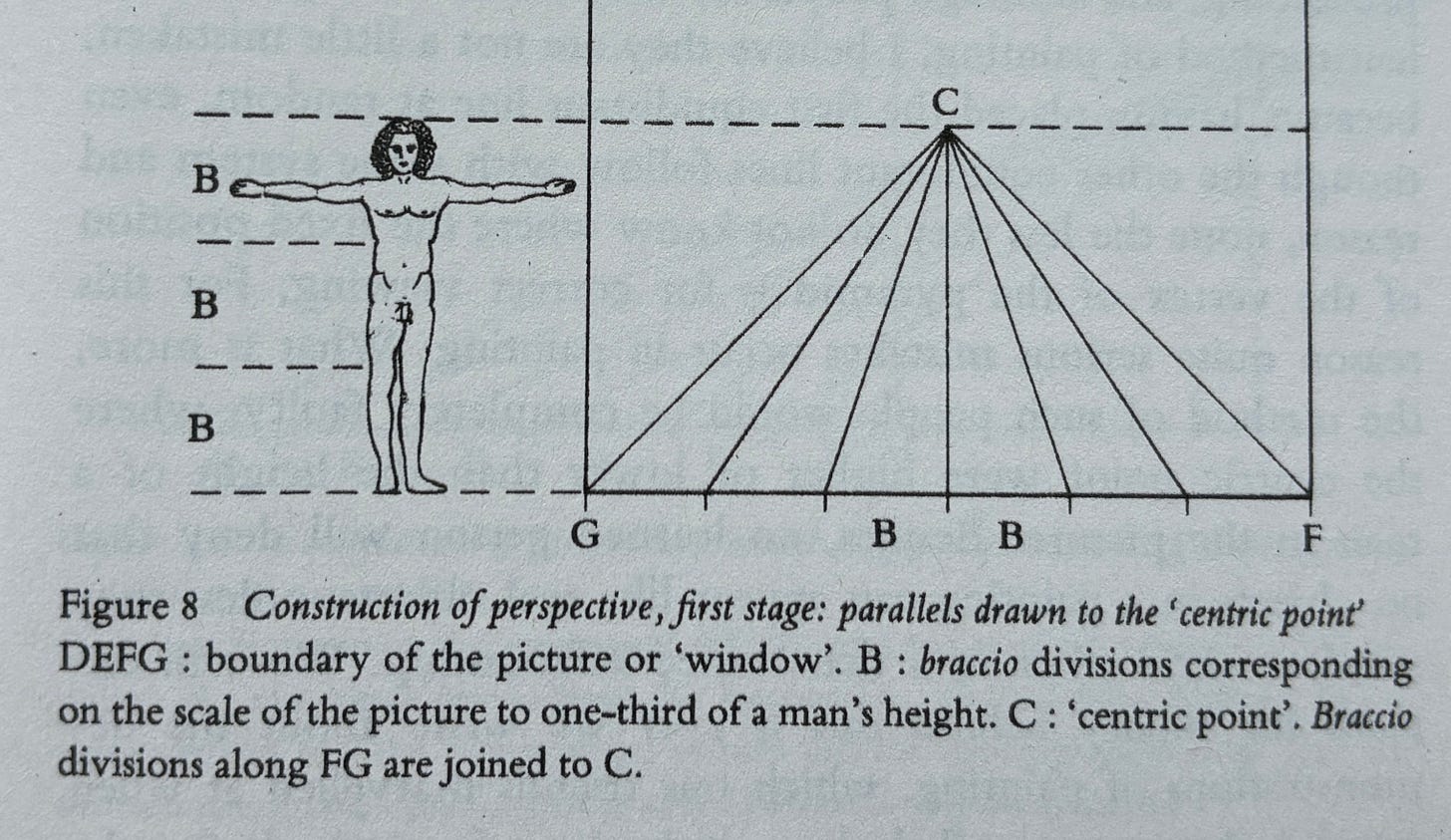

Alberti's treatise is both intricate and accessible, divided into three distinct books. The first explores geometry and the role of mathematical principles in painting. The second delves into practical techniques, such as composition, colour, light, and figure drawing. The third discusses the role of the artist in society.

While concepts like ‘perspective’ and ‘composition’ might seem like obvious elements of art today, when Alberti was writing, these ideas were only just emerging as central to visual practice! This was the dawn of the Renaissance, long before the time of Michelangelo and Raphael. Pioneering artists like Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Masaccio had only recently then begun experimenting with these revolutionary techniques, setting the stage for the transformative period that followed.

One final thing to note about On Painting is that it is also packed with delightful little diagrams which make you feel like a real Renaissance scholar! So this book is definitely one for the polymaths.

I say the function of the painter is this: to describe with lines and to tint with colour on whatever panel or wall is given him similar observed planes of any body so that at a certain distance and in a certain position from the centre they appear in relief, seem to have mass and to be lifelike. The aim of painting: to give pleasure, good will and fame to the painter more than riches. If painters will follow this, their painting will hold the eyes and the soul of the observer.

For the easy readers: Natasha Solomons I, Mona Lisa, (2022)

If you’re eager to learn about life and art in the High Renaissance, but you’re more drawn to relaxed, accessible contemporary fiction than to traditional art criticism, I might recommend Natasha Solomons' recent novel I, Mona Lisa.

The narrative is told from the perspective of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. It traces her journey from Renaissance Florence, to the French court, to the Louvre in Paris. It reads like an imaginative piece of fanfiction — insightful, amusing, and refreshingly based in a real-life narrative.

I particularly enjoyed the early parts of the novel set in Leonardo's studio. These sections are loosely rooted in historical events, such as Leonardo’s painting of the Battle of Anghiari (a work that deteriorated over time and is now lost). Historical figures like the graceful young Raphael, the cunning Machiavelli, and Michelangelo (depicted as unwashed and ill-mannered) make appearances. I loved this characterisation of Michelangelo… it felt quite plausible given his reputation for being famously grumpy and sombre (for example, Michelangelo denied the Pope entry into the Sistine Chapel while he was painting the ceiling).

At its core, this novel frames itself as an unrequited love story between the painting and her creator, Da Vinci. If mawkish romance isn’t your cup of tea, this book may not be either. But if you’re in the mood for a light, entertaining read with a blend of history, art, and sentimentality, you’ll enjoy it.

I meet Michelangelo’s gaze, pierced with exuberance in spite of my repugnance. The man is insolent and boorish and cruel, yet he is touched by God. He can hear my ‘voce’. He smiles at me and, despite his yellow teeth, it has surprising sweetness. He reaches out towards my cheek and I see the coarseness of his fingertips where they have been grated away by the stone.

For the historians: Mary Hollingsworth, The Medici (2017)

If you’re more into factual history (or perhaps Game of Thrones) you simply have to delve into the story of the Medici family.

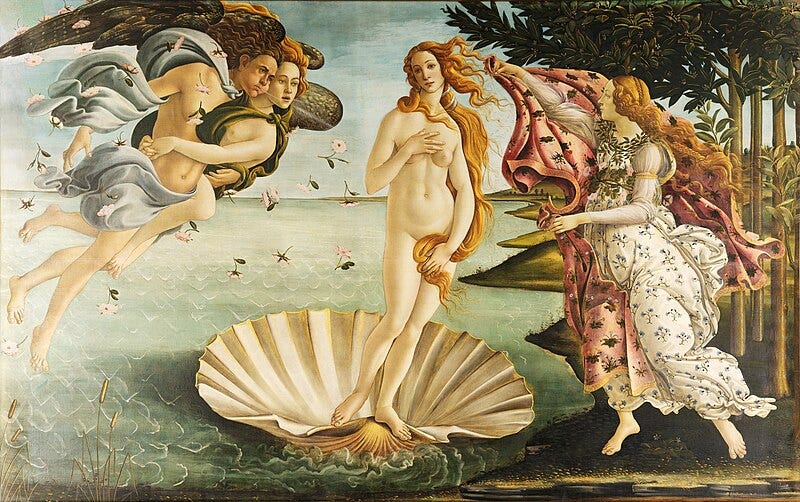

The Medici were the intermittent rulers of the Republic of Florence from 1434 to 1737. They were prolific patrons of the arts and played a crucial role in fostering the Italian Renaissance, supporting artists, architects, and scholars. Indeed, the Medici were behind some of the most iconic works in Western art, such as Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and Primavera, Michelangelo’s David, and Benozzo Gozzoli’s Procession of the Magi.

Mary Hollingsworth’s The Medici offers a comprehensive introduction to the complex lives of the family. It is clearly organised, well-researched, and contains sumptuous illustrations — something which I think is crucial when you’re addressing powerful art-patrons in the Italian Renaissance, since you absolutely want to see what all the fuss was about.

A note of caution: this is not an art book. Rather, it provides essential context for understanding Italian, Florentine, Renaissance art, exploring how and why it was created. Hollingsworth focuses on political alliances, financial conflicts, and the role of art and culture as a form of political currency. During this period, art wasn’t displayed in blank-walled galleries as it is today. Instead, it adorned places of power: religious spaces, palaces, and civic buildings. If you had a work like Gozzoli’s Magi or Michelangelo’s Night in your family chapel (as the Medici did), you were definitely a big deal.

The family attended mass in their own private chapel, which was lavishly decorated with gilded frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli depicting the Journey of the Magi - in which the family’s own portraits mingled with those of many political supporters among the riders in their superb cavalcade.

For the aesthetes: Walter Pater, The Renaissance (1873)

Walter Pater is a Victorian aesthete, and that means he prioritises personal feelings over everything else. He believes in ‘art for art’s sake’. He is only interested in how art makes the viewer feel, and not, for example, in its wider significance in politics, society, or history.

If you like Oscar Wilde, or maybe some of the Romantic poets (like John Keats), I think you’ll like Pater. If you’re a highly principled person (maybe you think art should have an underlying moral message, or social impact) or maybe if you’re a historian (perhaps you love accuracy and factual context) I think you would greatly prefer Jacob Burckhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) or, more recently, Michael Baxandall’s Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972).

Despite its amorality, Pater’s Renaissance is a fabulous, poetic, and profoundly delightful read. It is a series of essays, so you can easily dip in and out of it, focusing on the parts you’re the most interested in, and leaving the rest. My favourite chapter is ‘The Poetry of Michelangelo’ which contains a famous description of Michelangelo’s style as ‘sweetness and strength’.

Pater’s prose is deeply intimate, and primarily focused on the emotions and sensations inspired by art. You don’t need to read Italian, or have studied art history, to know how a painting makes you feel — so in some ways Pater’s reading of the Renaissance is the most inclusive of all.

the critic should possess … a certain kind of temperament, the power of being deeply moved by the presence of beautiful objects. He will remember always that beauty exists in many forms. To him all periods, types, schools of taste, are in themselves equal. In all ages there have been some excellent workmen, and some excellent work done. The question he asks is always:—In whom did the stir, the genius, the sentiment of the period find itself? where was the receptacle of its refinement, its elevation, its taste? "The ages are all equal," says William Blake, "but genius is always above its age."

Fin.

Thanks for this list! I'm always looking for art related books but find it so difficult to sift through the internet for the good ones. I'm looking forward to reading a couple of these.

This is an excellent post, informative and inspiring at the same time. I very much enjoyed reading this! Oh, and I, too, have just put the Medici book on my reading list.