The Golden Age: A Reading List

Why Christmas is the perfect time to get to know the Dutch Golden Age

I’ve been putting up my final festive decorations this week. My new favourites are some battery-operated electric candles, and I’ve got so enthusiastic about them that I’ve actually stopped using overhead lights. Since the evenings are at their shortest in London in December, I’ve been spending most of my time sitting by this (electric) candlelight. I’ve also been collecting food for a party I’m about to throw. I’ve got bags and bags of food and fake mistletoe galore.

And you know what all this makes me think of? Dutch painting. Specifically, seventeenth-century Dutch painting, or the Dutch Baroque. The Golden Age.

Christmas-time is Dutch Golden Age time: not just because of the fruit and candles, but also, crucially, the messaging. This period of art emerged from an era of great wealth in Dutch history (when Holland was a powerful mercantile nation). It is full of indulgence and celebration: parties, rich food, buxom ladies, and salacious innuendo.

However, in Golden Age art, this visual language of indulgence is conversely beset by strict Calvinist values. Yes, the seventeenth-century Dutch were living copiously, but they were also terrified of taking too much pleasure in worldly goods. So they satirised, and expressed ambivalence, and false modesty, and filled their pictures with complex layers of meaning.

These paintings are full of morals we could all do to be more mindful of as we enter the festive month. They present similar morals to those which we’ll be replaying in our favourite Christmas movies (The Grinch, The Nightmare Before Christmas…). That is: that festivity is not supposed to to be about gifts and gluttony, but instead about gratitude and humility.

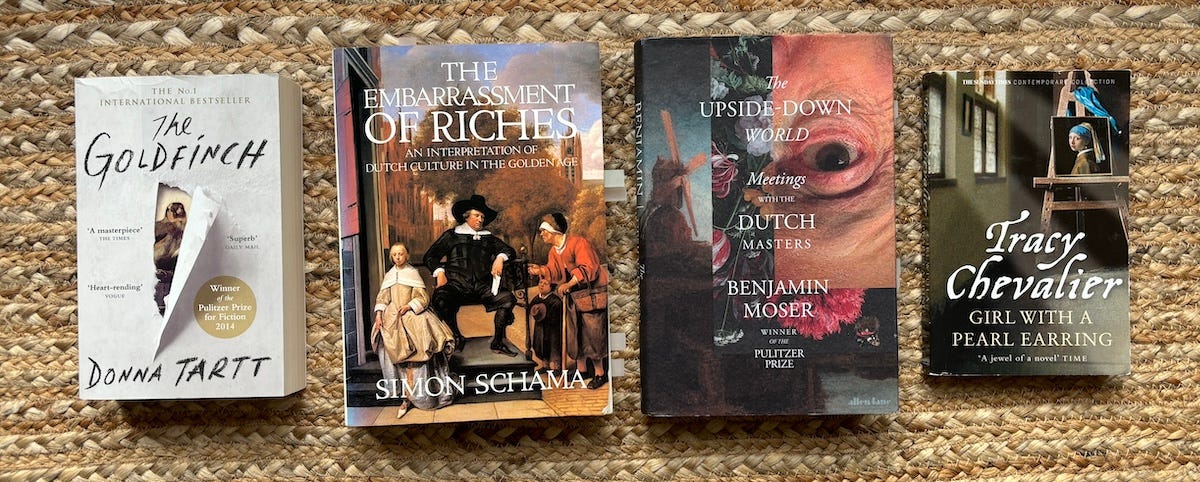

Want to learn more? Here are some great books on the Dutch Golden Age of painting to whet your whistle (or kleipijp).

For the Generalists: Simon Schama

The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (1991)

This book is, in my opinion, the one-stop shop for historians, art historians, anthropologists, and anyone interested in politics, economics, religious reformation, or social development — anyone with a vaguely academic interest in Dutch history. Although it isn’t outrightly categorised as an art history book, it is one of the most in-depth and protracted art-historical examinations I’ve ever seen. This work is filled with prints and illustrations, creating an almost entirely visual narrative. Each chapter focuses on a distinct thematic element (food, power, money, etc.), richly illustrated with works by the period’s big hitters — Jan Steen, Frans Hals, Jacob Cats, and others.

Schama doesn’t limit himself to any one topic, and because of this, he is able to confidently situate Dutch art and literature with complete freedom. He talks about domestic life: sanitation, daily habits, what people ate and talked about.

The only problem with this book is that it’s very, very long — but perhaps that is the price you pay for this level of detail.

Dutch art invites the cultural historian to probe below the surface of appearances. By illuminating an interior world as much as illustrating an exterior one, it moves back and forth between morals and matter, between the durable and the ephemeral, the concrete and the imaginary, in a way that was peculiarly Netherlandish.

For the Fantasists: Tracy Chevalier

Girl with a Pearl Earring (1999)

I like for my reading lists to have a wide appeal, so I always include a fictional element for those who prefer the intimacy of imagined narratives. Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, written in the 1990s, has really stood the test of time, and in 2003 it even procured a cinematic adaptation, with Scarlett Johansen and Colin Firth.

If you enjoyed The Marriage Portrait (Maggie O’Farrell) or I, Mona Lisa (Natasha Solomons) you might also appreciate the sensitive, romantic perspective Chevalier brings. Like these more recent novels, Chevalier’s book thoughtfully subverts the traditional ‘male painter, female sitter’ dynamic by telling the story from the viewpoint of Griet, a young Dutch maid whose relationship with the artist Johannes Vermeer leads to the creation of his famous painting.

Chevalier’s book offers a very different perspective on Dutch Golden Age art than Schama’s, but it’s equally vivid — with the added benefit of dialogue. The novel paints a creative picture of life, relationships, romance, and spirituality in the period, with fascinating imagined scenes of Vermeer’s process, from paint-mixing techniques to the operations of his studio. But be warned: this is pure fiction. Historians know very, very little about Vermeer (which might be exactly why he’s a perfect subject for historical fiction)!

‘There is a difference between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to painting,’ he explained as he worked, ‘but it is not necessarily as great as you may think. Paintings may serve a spiritual purpose for Catholics, but remember too that Protestants see God everywhere, in everything. By painting everyday things - tables and chairs, bowls and pitchers, soldiers and maids - are they not celebrating God’s creation as well?

For the Dabblers: Benjamin Moser

The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters (2023)

I think that the mark of a truly great book (or any work of art, for that matter) is one that operates on multiple levels. Benjamin Moser’s The Upside-Down World is certainly one of these. You can savour it slowly, chapter by chapter, or devour it in a single sitting. It’s a wonderfully realised, comprehensive overview of Dutch painting —equally at home on an academic reading list or a tasteful coffee table.

Each chapter in Moser’s book serves as a standalone study of a Dutch master. He begins with Rembrandt, then moves seamlessly between other greats like Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, Jan Steen, Frans Hals, Rachel Ruysch, and many other (lesser-known) masters. Beautifully illustrated and meticulously researched, these sections are interwoven with Moser’s personal anecdotes. Not only do these asides give voice to Moser’s personable, inquisitive character, but they also add a relatable, personal touch. Viewed more broadly, this book is a kind of memoir, which sets it apart from strictly academic art history publications.

Moser moved to the Netherlands at twenty-five and claims he has been trying to understand the country ever since. This book is a testament to his insights, and relates an impressive grasp of seventeenth-century Dutch art. It’s also cognisant of the tensions inherent in that art (between excess and restraint, humour and seriousness, realism and symbolism…) and relates these ambivalences to contemporary life with clarity. Highly recommended!

The Holland that I had learned to see through the prism of the Golden Age artists was a country that had never really quite existed. Yet it had a reality that was far more convincing than whatever other reality skulked behind those images. That reality, lost with the passing of the centuries, no longer mattered, or not exactly.

For Everyone: Donna Tartt

The Goldfinch (2013)

This wildcard is not really about the Dutch Golden Age at all… sorry!

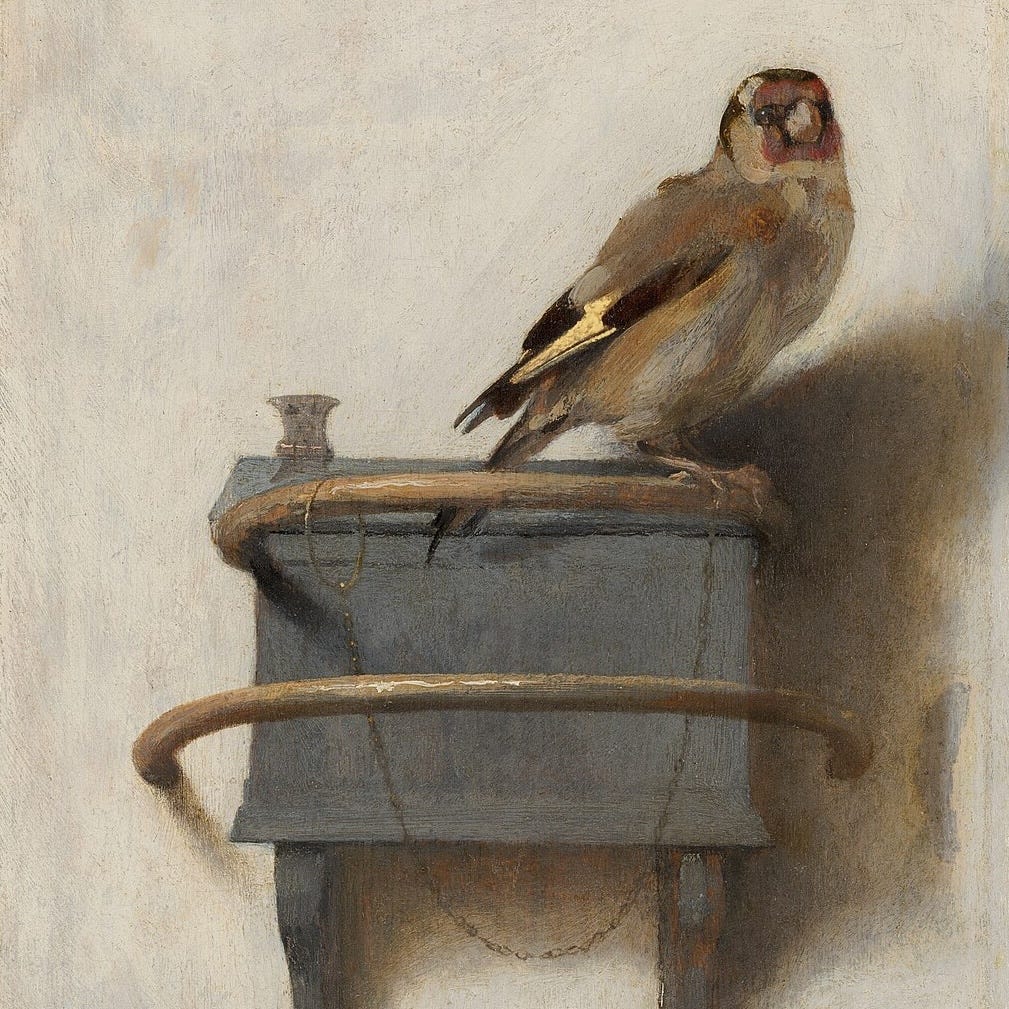

However, this expansive, epic, sensitive, Pulitzer Prize-winning narrative is still framed around one of the masterpieces of the Dutch Baroque, Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch (1654), so I had to include it here.

Fabritius’ Goldfinch is a very unique painting — quite ahead of its time in terms of technique (loose) and composition (minimalist). It’s a symbol of spiritual endurance and pathos (note the chain on the bird’s foot…).

So powerful is the presence of this image in Tartt’s book, that you would not be wrong to call it one of the main characters. Without giving too much away, the protagonist, Theo Decker, is obsessed with Fabritius’ painting, and it takes on different symbolic roles throughout his life.

Tartt’s novel is brilliant (not quite as brilliant as The Secret History, but brilliant nonetheless). It sprawls. It expands and retracts. At times you want to throw it across the room, because it evokes boredom and confusion so acutely well that you start to feel them yourself.

If you haven’t read anything by Donna Tartt — brace yourself. She does not shy away from pages and pages of misdirection, untimely deaths, big questions, and philosophical ambiguity. Best of luck, she might become your new (or old) favourite writer.

“He was ‘a pupil, Vermeer’s teacher,” my mother said.

“And this one little painting is really the missing link between the two of them-that clear pure daylight, you can see where Vermeer got his quality of light from. Of course, I didn’t know or care about any of that when I was a kid, the historical significance. But it's there.”

I stepped back, to get a better look. It was a direct and matter-of-fact little creature, with nothing sentimental about it; and something about the neat, compact way it tucked down inside itself-its bright-ness, its alert watchful expression-made me think of pictures I’d seen of my mother when she was small: a dark-capped finch with steady eyes.

I hope you find something interesting in this list to distract you from the ribaldry of Christmas parties and succulent feasts. Which, ironically, is sort of what the Dutch Masters were trying to do anyway.

If you enjoyed this reading list, why not check out the others in this series?

Three Must-Reads for Art Lovers

Reading around the Renaissance

Which period should I do next? Suggestions welcome.

Fin.

Fabulous read! I have every book but Moser. That will be going on my Christmas list! In January of this year, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art had a wonderful exhibition called “World Made Wondrous,” which recreated a Dutch collector’s cabinet to examine the political and colonial histories of European collecting practices in the 17th century.

The “thesis” was that as Europeans assembled their curiosity cabinets, they ordered the world in deliberate ways and asserted judgments and hierarchies on the value of natural materials, labor, craftsmanship, and human worth. It was absolutely fascinating and certainly one of the most well executed exhibits I’ve ever seen.

One of the finest books on art runs on a parallel path to your own so I would highly recommend Duveen by SN Behrmann, who was actually a journalist for The New Yorker. His pithy, gossipy account of Joseph Duveen, arguably the greatest art dealer of all time, brilliantly captures the caprice of the man and his age. In his pomp, roughly 1895-1935, Duveen had virtually every tycoon you can think of in his pocket. His masterstroke was realising at the turn of the last century that America was full of money but no art whereas Europe was full of art but no money!