3 Art Books to Change Your Perspective

The three books which changed my outlook on art theory and history

I want to share a quotation with you which changed the trajectory of my life.

I was in the first year of my undergraduate degree, studying English Literature. Our coursework exam papers had just been released. These were a list of questions and phrases, and our task (a 2,000-word essay) was to explore the questions they elicited – usually related to language, politics, or philosophy.

This was the one I chose:

We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.

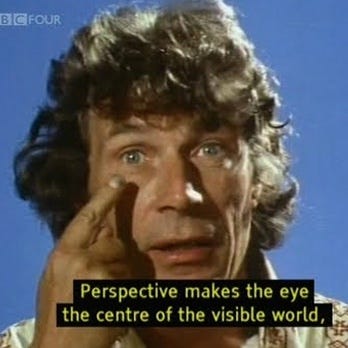

It’s from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972). This is a book adapted from an educational four-part television series, produced by the BBC.

It’s about how what we see is filtered through the frameworks around us, and I think it’s probably one of the most important books on art theory written in the twentieth century. It’s a beautiful, multimedia collection of essays (both written essays and essays in pictures). It changed my life because it was one of the first times I was presented with the opportunity to write about art in an academic setting – which is sort of where I find myself today.

So, what is art theory? What does Berger’s quotation actually mean?

Imagine this: you, a contemporary viewer, see a painting by Paul Gauguin. Although you might notice the fine craftsmanship of the work, your response will always be determined by what you already know and the society you grew up in. You may, for example, note that Gauguin’s treatment of colour and shape is innovative — but you would only know this if you were aware of what was being produced by other French artists at the time. Moreover, you may (or may not) have thoughts about his subject matter. Your perception will be influenced by your personal ideas about the representation of women and indigenous cultures by a Western man.

According to John Berger, seeing is never neutral. It’s an active process where meaning is created through the relationship between the object, the spectator, and the world that spectator lives in.

Looking at art can never be objective. How we see (art theory) is just as important as what we see (art history).

But we don’t have much control over what we see — at least not in museums and galleries, whose collections often reflect a certain narrative of art history. This is a narrative which has historically represented mostly wealthy, white men… because these were the demographic running the governing bodies!

For a long time, women (and many other minority groups) were not permitted to undertake a formal artistic education. Many types of art — like folk art, crafts, ornamental arts, and even arts which we now consider to be ‘fine arts’, like engraving –— did not make their way into the history books. And the result is that we, as a culture, have almost forgotten about them!

This is why Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men (2022) is so critically important. ‘If we aren’t seeing art by a wide range of people,’ she writes, ‘we aren’t really seeing society, history or culture as a whole.’ Her point is that ‘art history’ is itself based on narratives written by writers (like Giorgio Vasari and E. H. Gombrich) who are, of course, great, but don’t account for artists outside of the conventional, male-dominated world.

There are so many reasons for this, and Hessel’s subject is richly tapestried and complex. Despite this, her book is a profoundly accessible read, and I would recommend it to anyone looking to reframe their idea of how we see.

With this book, I think Hessel has opened the way for further, similarly refreshing takes on the conventional ‘story of art’. For instance, I’d love to see a ‘story of art’ from a non-Western tradition (Japanese or Indonesian, for example); or, perhaps, the ‘story of crafts’ (think needlework, weaving, knitting, whittling, carving etc).

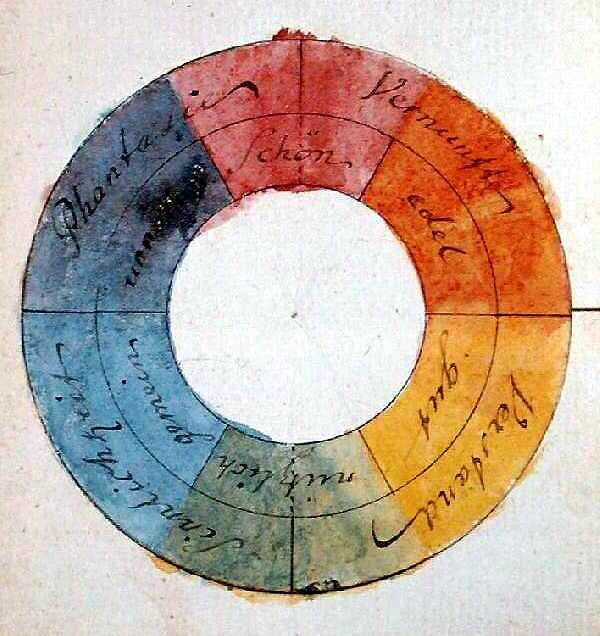

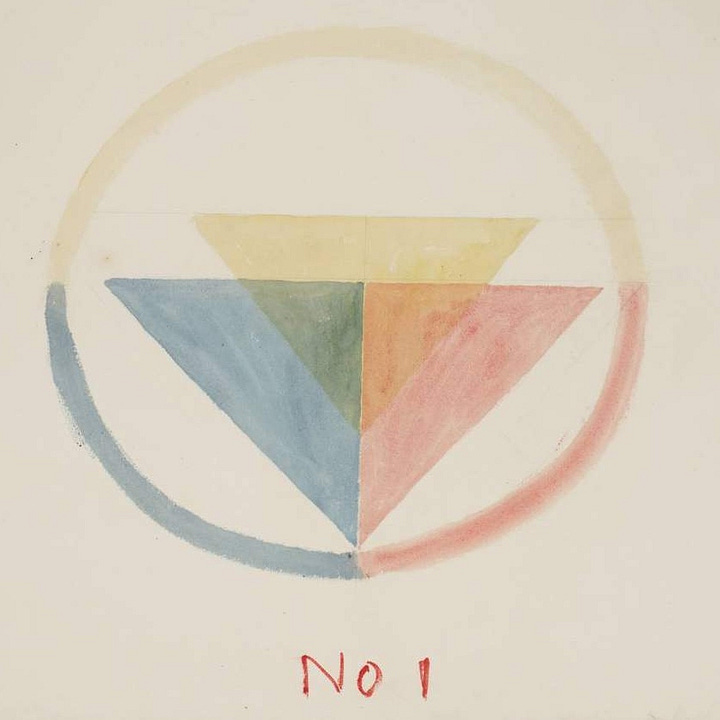

So then, if you are enticed by the idea of learning a more global perspective on how we look at art, you have to read James Fox’s The World According to Colour.

This book is like a quilt. I mean, literally: it’s a patchwork study. Each chapter is dedicated to a single colour. It’s made up of different cultures, stories, and anecdotes, combining natural history with anthropology, and physics with aesthetics.

The book sort of blurs the differences between art history (again, what we see) and art theory (how we see), but I’d categorise it as a work of art theory because it’s not centred around a movement or period of art. It’s about colour.

James Fox’s writing reminds me of that of Simon Schama, whose book on the Dutch Golden Age, The Embarrassment of Riches, I recommended in a previous reading list. Like Schama, Fox is unafraid to take unexplored paths and go down alleyways of digression that add much value and character to the subject. Also like Schama, Fox is something of an art history TV personality. He appears in a number of BBC series which go far beyond the remits of the art museum.

Unlike Schama, however, Fox knows how to keep it concise. The World According to Colour is tightly structured. You could read it in a day. Schama’s work is brilliant but sprawling, while Fox distils his insights into a concise, digestible form.

Fox’s book was a revelation to me because, a bit like Hessel’s, it showed me how the art historian could (and in fact simply must) bridge the gaps between academic and mainstream, and think about art as a global, cultural force, rather than a strict list of canonical names, just waiting to be ticked off. Van Gogh, Caravaggio, Monet: these men are characters in the same ‘story’ as Ming dynasty ceramicists, prehistoric cave painters, and Mayan jade-sculptors. They’re using the same colours and materials, in different ways, to invoke an emotional response in the viewers.

It is only by first becoming aware of and then critically thinking about what factors influence how we look at art, that we can begin to truly understand just how important it is.

Once we become aware of the gaps in our knowledge can we attempt to fill them. This is why art history cannot survive without art theory: because if we don’t know how we’re looking, how can we possibly know what we are looking at?

Thanks for reading! Check out my socials @culture_dumper (Instagram) and @Blakefart (X / Twitter) for updates on my academic work, life, and current exhibitions.

Also, if you enjoyed this reading list, why not check out the others in this series?

I’m a huge fan of Ways of Seeing! Sometimes I pull it off the shelf and dive into random pages—it always feels fresh and thought-provoking. I’m definitely adding the other books you mentioned to my reading list!

You may of course know of this, but there is a gorgeous, unique volume of correspondence between Berger and John Christie, titled ‘I Send You This Cadmium Red…’. It’s about colour (obvs) and so much more - a really rich and special book. That’s a great trio of books you’ve referenced btw, and a clever, succinct reflection on the necessity of art theory. Thank you.